Bang, crash! Watch out for the falling light! Don’t stand under that toppling tree! Those trapeze wires don’t look very reliable! There should be at least one special Tony Award for Mischief Theatre’s Peter Pan Goes Wrong (Ethel Barrymore Theatre, booking to July 9)—not just for its technical brilliance, and the raucous, daffy, side-splitting pleasures it delivers to the audience, but also as a badge of proof that the British may have finally, successfully exported pantomime to America.

The children (and adults) at the performance this critic attended were absolutely on point with their “Behind you” shouting at the right moments in this deliciously ridiculous, joke-, absurdity-, and physical comedy-stuffed “awfully big adventure” on Broadway written by Henry Lewis, Jonathan Sayer and Henry Shields, adapted from the original stage play by J.M. Barrie.

The actors in the show, which include its writers, are playing multiple characters—both the members of a hapless, accident-prone, utterly unprofessional British college dramatic society, and the characters in Peter Pan these amateurs are trying to play in a production that has disaster written multi-definitionally all over it. With every small and large-scale mishap that befalls the end result, the title of the Broadway show more than lives up to its name.

Just as in the Mischief’s previous, just-as-fizzing The Play That Goes Wrong (also written by Lewis, Sayer, and Shields), it is not just the cataclysmic stuff of sets falling to pieces that are done so well, but the smaller, visually satisfying gags, the silly jokes (such as the face of a dog outfit falling off), the quieter moments of humor (lines being missed; props being misued, broken, or lost; lights and electronic contraptions on the blink), that are just as well-executed as the bravura sequences, such as when the Darling children’s bunk beds concertina into each other squashing each of them. Despite all the loud chaos, Peter Pan Goes Wrong celebrates—very sweetly in its closing moments—the joy of putting on a show.

Henry Shields’ Chris plays Captain Hook in the amateur production, but exasperatedly turns on the children out of character—as an actor and president of “the Cornley Polytechnic Drama Society,” frustrated that what he intended to be a searing piece of adult drama has become a boo-hiss pantomime. Don’t shout out the wrong things, he rails at the children, some of whom he deems ugly.

He is striving for excellence in theater, dammit, and how flawed and fruitless this aspiration is makes for great comedy. A sequence in which, as Hook, the Olivier Award-winning Shields cannot remove something because of his actual hook—seeking the help of the audience—becomes unfeasibly hilarious and excruciating. (There is a reason why Mischief’s productions have played in 40 countries around the world, delighting adults and children.)

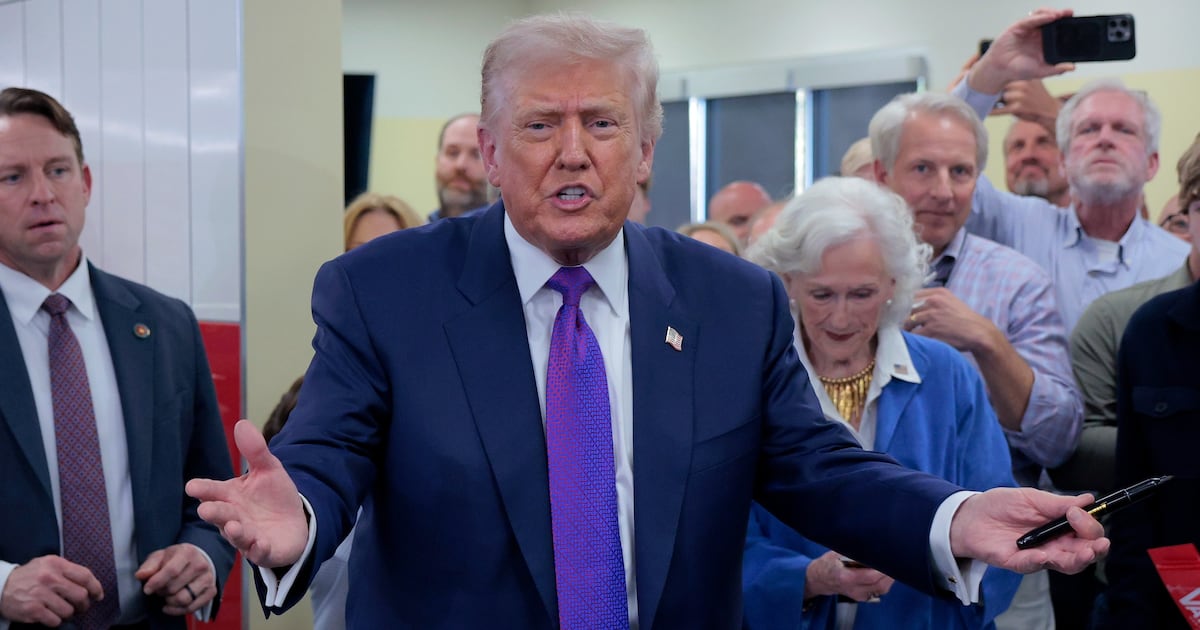

Neil Patrick Harris in 'Peter Pan Goes Wrong.'

Jeremy DanielUntil April 30, Neil Patrick Harris is in the show, playing the Narrator, and he, like everyone else, quite literally throws himself into the show—throwing handfuls of glitter to announce his arrival, while also imperiled by a chair that appears with random intent, ready to fell him at any given moment. The Olivier Award-winning Henry Lewis as Robert, co-director of this “Peter Pan” alongside Chris, first of all addresses us gravely, with a litany of foreboding news making clear how amateurish things may turn out to be; we learn that one actor, Dennis, will be wearing a headset, so the producers can feed him lines—his true portrayer, the Olivier Award-winning Jonathan Sayer, makes this is a not-tiresome ongoing joke, right up until its crescendo, when he repeats word-for-word a backstage marital breakdown.

Robert also plays Nana the dog, who gets stuck in a door, causing anguished minutes of practical upheaval. Later, he plays Peter Pan’s shadow—a shadow who is not only a terrible shadow, but also determined to hog scenes. Mischief co-founder Nancy Zamit as Annie provides early wows for a sequence of blinkingly fast costume changes between Mrs. Darling and maid Lisa.

Shields—who is a dead ringer in looks and tone for John Cleese as Basil Fawlty—is also the archetypal Cleese-ian ringmaster of chaos, desperately and futilely wanting this production of Peter Pan to be as professionally executed as possible. But everything goes wrong: scenery shakes and fails, lights fall, flashes of sparks appear.

To construct and then merrily destroy a production from within takes even more skill than a conventional production—Adam Meggido’s direction is a mischief- and stage madness-embracing wonder, with the vital support of Simon Scullion’s stage design, Roberto Surace’s versatile costuming, Matthew Haskins’ lighting, Ella Wahlström’s sound, and Adam John Hunter’s stage management. Keeping things so tightly together under the guise of tearing things apart takes a very special set of skills.

The show does not just dwell in chaos. Mischief’s co-founder Charlie Russell plays Sandra playing Wendy as an intense and self-contained actor, who off-stage is involved with a Peter Pan (Greg Tannahill), who when it comes to Jonathan—the actor playing him—is no hero.

Instead, the audience hopes she gets it together with the actor Max (Matthew Cavendish), who plays Michael Darling and the Crocodile (in ridiculous, fluffy crocodile outfit, appearing on stage maneuvering on a little trolley). Max is the charmed presence at the heart of the Cornley theatrics; we learn first the production has been made possible by a sizeable donation from the uncle; quite unlike Robert’s underfunded Jack and the Bean (get it?). There is a rumble of wounded outrage among the audience when Robert’s true feelings about Max—“He cannot act to save his life. He’s terrible as Michael, and the crocodile. He’s playing it like a mammal”—are overheard by Max.

Chris Leask plays Trevor, Cornley’s stage manager, who emerges as a quiet hero as he tries to save the actors from various disasters, until he makes the fatal error—after injury fells Jonathan—of playing Pan himself. Oh Trevor, bad move! Ellie Morris plays Lucy, Chris’ niece who is frozen with stage fright, and also a magnet for every possible physical injury a badly overseen production could cause an already terrified human. (One thing: Bianca Horn as Gill, a stagehand and paramedic, should have more fun things to do.)

The production excels in the mêlée it conjures from the harum-scarum flying scenes, and then—at the end—a thrilling and crazy sequence where the out-of-control revolving stage brings together all the on- and offstage dramas in a whirling dervish of kinetic and frozen tableaux, as characters scramble from one set to another, eventually just trying to escape further injury and finish the play physically intact.

The real surprise is that the ending of both Cornley and Broadway show is quiet and resonant, as a moment of victory for one character we have felt so bad for, and an underlining of the spirit of magic within Barrie’s original—and the art and passion of creating theater. No joke.