There’s a scene near the end of season two of Ricky Gervais’ Netflix series After Life in which his character Tony, a small town journalist, and his photographer colleague Lenny go to report a story on a 50-year-old man who “identifies as an 8-year-old schoolgirl.”

When they arrive at the man’s house, he’s wearing a flowery dress and pigtail wig. “I’m trans,” the man says. “Deal with it.” When his wife says he’s having a “breakdown,” he accuses her of being “transphobic.”

“I haven’t got a problem with trans people—real trans people,” the wife explains. “I couldn’t give a shit what gender people want to be, or become, or what they want to be called, or how they want to dress, or whether they keep their knob or the fanny they were born with. I couldn’t give a shit. But you are not trans, you’re having a fucking breakdown.”

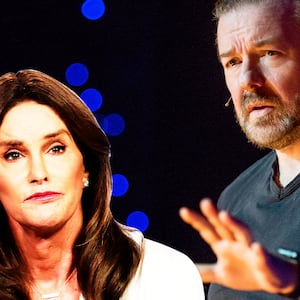

It’s hard to watch this scene without thinking about the controversy that has dominated Gervais’ comedy career for the past decade. During our conversation on this week’s episode of The Last Laugh podcast, I asked him if this was his way of commenting on the backlash to his Caitlyn Jenner jokes.

While Gervais resists drawing a direct line from his real-life controversy to that moment from his latest fictional television show, it is clearly something that gets under his skin.

“Most offense comes from people who mistake the subject of a joke with the actual target. And they’re not necessarily the same,” he says. “I’ve had it throughout my career. So there, you know, ‘He’s making fun of a trans person, therefore he’s transphobic,’ which is very odd. That would suggest that you can never make fun of a trans person for any reason. Even if it had nothing to do with their trans-ness.”

This is the defense that Gervais has used repeatedly in the past, both in interviews and in the opening section of his 2018 stand-up special Humanity.

When the comedian hosted the Golden Globes for his fourth time in 2016, it was not long after Jenner had come out as trans. “I’m going to be nice tonight. I’ve changed,” he said near the top of his monologue, before adding, “Not as much as Bruce Jenner. Obviously. Now Caitlyn Jenner, of course.”

“What a year she’s had!” he continued. “She became a role model for trans people everywhere, showing great bravery in breaking down barriers and destroying stereotypes. She didn’t do a lot for women drivers. But you can’t have everything, can you? Not at the same time.”

For Gervais, the target of that extremely dark joke is the fatal car crash that Jenner was involved in before her transition. Much of the criticism he received at the time had to do with the way he misgendered or “deadnamed” Jenner at the top of the joke, something he said he learned was viewed as offensive only after the fact—but continued to do for comedic effect in his special.

As Samantha Allen wrote for The Daily Beast in March of 2018, “Gervais pretends as if he’s going to explain why his original joke wasn’t transphobic, but, as so many comedians tend to do, he doubles down instead, grotesquely and inaccurately describing the practice of male-to-female sex reassignment surgery as having ‘your cock and balls ripped off and a hole gouged out.’ By the time Gervais has got it all out of his system, a quarter of his special is over. His return to stand-up will forever be 25 percent transphobia, 75 percent everything else.”

“It’s like they’ve created a dogma around it, that this should never be joked about,” he says now of his critics. “But why shouldn’t it be joked about it? It depends on the joke. That’s absurd.”

“I’ve seen it with so many issues,” he continues. “People saying, we want to be treated the same as everyone else, but not in jokes. And I want to go, that’s asking for privilege, that’s not asking for equality. If you joke about everything, you joke about everything. Dogma used to be confined to religion and other cults, but now it’s come into identity politics. They want to shut you down.”

When people “put ‘phobic’ on the end of a word,” as many have done, labeling him “transphobic,” Gervais says, “What that means is, ‘Shut up! Shut up!’ That’s all that means. Just because someone accuses you of something, it doesn’t mean that it’s true. I see it all the time.”

He goes on to compare it to people shouting “racist” or “sexist” at someone with no basis. “They think that it means something,” he says. “And what it means is they want you to shut up.”

Of course, he has no intention of shutting up. And he mostly blames the media for stoking what he views a faux-outrage.

Gervais is particularly alarmed by headlines—even in “reputable” newspapers—that read, “So and so said a thing and people are furious.”

“No one’s furious!” he exclaims. “They wouldn’t even have heard about it if you hadn't printed it. So it’s bullshit. It’s fake outrage. No one’s outraged. No one’s annoyed. No one cares.”

For Gervais, this frustration is something he’s been dealing with for much of his career. “I do jokes about every awful atrocity in the world. And people laugh at 19 of them and they don’t laugh at the 20th because that happened to them,” he says. “Everyone thinks that their thing is more important and worse than yours.”

“When I do a joke about famine, they know I don’t mean it,” he adds. “Or cancer, they know I don’t mean it. Or AIDS. But when I do a joke about their thing, they go, ‘Mine’s misunderstood. He might mean it with me.’ Because they can’t see the wood for the trees. Because it’s an emotive reaction and comedy is an intellectual pursuit.”

Gervais says it still “annoys” him “when people think a joke is a window to the comedian’s true soul” because “nothing can be further from the truth.”

“I’ll flip a joke. I’ll pretend to be something I’m not, if it makes the joke better,” he admits. “I’ll pretend to be right-wing, left-wing, no wing. It depends on the joke. The comedian’s true feelings shouldn’t come into a joke. Because it’s a magic trick, a joke. It should stand up by itself. Anyone should be able to tell it and it should still work.”

Gervais likes to remind anyone who will listen that there is no such thing as an “off-limits” topic in comedy and that “the line” is constantly moving in terms of what causes offense. As he has made clear in both his stand-up and on After Life, no amount of people telling him to “shut up” will make him stop trying to find comedy in the subject of trans people.

As Tony and Lenny are leaving the “trans” 8-year-old girl’s house on that show’s season two finale, Lenny delivers a surprisingly nuanced monologue—as written by Gervais—about the differences between people who used to be called “transsexual” or “transvestites” but now identify as transgender.

“It’s all got a bit serious,” Lenny says finally. “No one just dresses up as a bird for a laugh anymore.”

“Good,” Gervais’ Tony replies. “It was never that funny.”

Next week on The Last Laugh podcast: Former SNL cast member and actress Michaela Watkins.