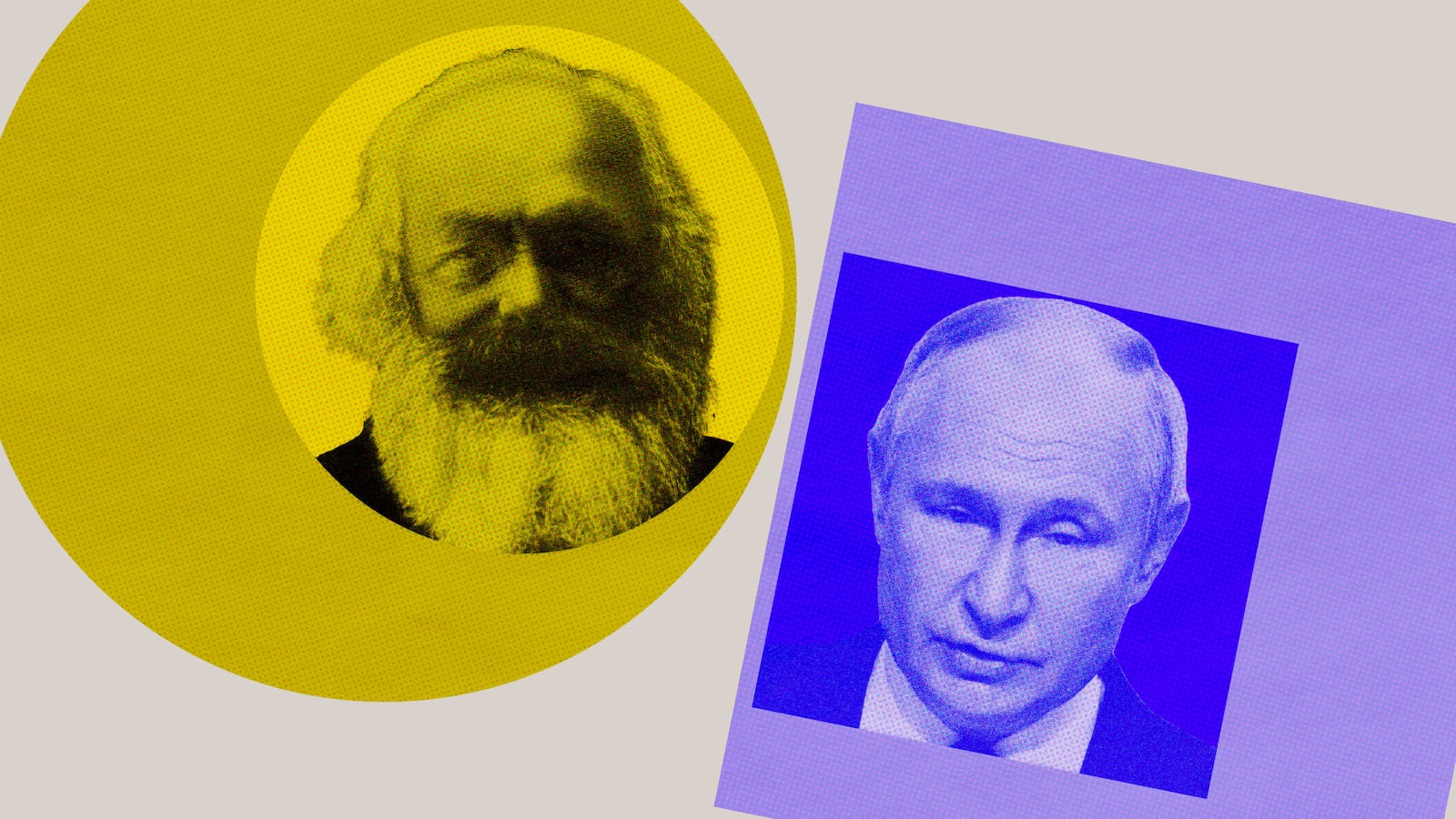

Sen. Kevin Cramer (R-ND) has some very strange ideas about history. In justifying his vote for a controversial aid package to Ukraine and Israel, he called Russian President Vladimir Putin “the modern Marx.”

There are so many layers of absurdity in that statement that it’s hard to keep them all straight.

Karl Marx was the most important thinker in the history of the socialist movement. He advocated an egalitarian society in which ordinary workers would democratically run the “means of production”—think farms, factories, and other engines of economic activity. He was bitterly opposed to imperial wars in which the lives of poor and working people were thrown away to further the interests of wealthy business-owners. Oh, and he was an adamant atheist who advocated a strict separation of church and state.

Vladimir Putin is about the furthest thing from any of that. He was the handpicked successor of Russian President Boris Yeltsin—the politician more responsible than any other for spearheading the dissolution of the USSR and the transition to capitalism in Russia.

The Soviet Union was authoritarian and economically dysfunctional in many ways, but it was a comparatively equal society where the privileges enjoyed by party elites were nothing like the wealth of Western capitalists. Russia today is a gangster-capitalist oligarchy with far greater disparities between rich and poor than most developed countries. Putin is currently waging exactly the kind of imperial war in Ukraine that Marx abhorred. And Putin heads a socially conservative government that gains much of its legitimacy from a cynical alliance with the Russian Orthodox Church.

Why Can’t Conservatives Remember There Isn’t a Soviet Union?

To be fair, Cramer isn’t the only right-winger to be a bit confused on this point. New York Post columnist Karol Markowicz recently told talk show host Dave Rubin that Putin’s talk of Russia’s land claims based on historic borders sounded to her like the rhetoric of “land acknowledgment leftie college kids.” A Compact magazine columnist somehow detected “quasi-Marxist analysis” in Putin’s comments on the Ukraine war to Tucker Carlson.

And at the beginning of that war, multiple high-level Republicans seemed to have trouble remembering the fall of the Soviet Union. Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin called Putin a “Soviet” dictator—even though the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics dissolved long before most soldiers who Putin sent to die in that war were even born. In fact, in his big speech when the war started, Putin blamed the USSR’s founder, Vladimir Lenin, for creating Ukraine as a distinct national entity.

Cramer’s Senate colleague Tommy Tuberville (R-AL) made an even stranger comment at the time. Explaining why Russia invaded Ukraine, he reportedly said, “It’s a communist country, so [Putin] can’t feed his people, so they need more farmland.”

Sen. Tommy Tuberville, R-Ala., attends the House and Senate committee markup of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 in Dirksen Building on Wednesday, November 29, 2023

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty ImagesThis is pretty wild stuff. The Soviet Union once took up a sixth of the land surface of the Earth, and its collapse at the beginning of the 1990s played out for many of its residents like a dystopian science fiction movie. There were wars and civil wars. There was an explosion of lawlessness and a steep rise in organized criminal gangs. In Russia, in particular, life expectancy plummeted. Those Russians who were lucky enough to join the new middle class certainly benefited from the transition, but others underwent tremendous suffering as what had been a state-owned economy was sold off to a handful of ruthless, politically connected “oligarchs.”

Calling Putin a “Soviet” dictator would be like calling Youngkin a “Confederate” governor or Tuberville a “Confederate” senator. Like the victory of the Union army in the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, the transition to capitalism in the former Soviet nations was a world-historic event–and it’s more than a little disconcerting to see senators and governors apparently forget that it had happened.

But it isn’t nearly as bizarre as calling Putin “the modern Marx.”

Marx vs. Putin

Even listing off the differences between Putin and Marx feels like the setup to an absurdist joke—like asking what the top five differences were between Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Mongol warlord Genghis Khan.

Calling any of the leaders of the Soviet Union “the modern Marx” would have been absurd. Associating him with the brutally inegalitarian society that emerged after the USSR’s collapse—which shared with the Soviet past only the absence of core democratic rights—is fantastical.

Marx wrote eloquently about the folly of censorship and the importance of freedom of the press. He opposed the death penalty. He never advocated any sort of one-party dictatorship. Nor did he support any dictator who held power during his lifetime. As far as I know, the only living head of state he liked enough to even send a friendly telegram was the democratically elected Abraham Lincoln—who he supported for standard anti-slavery reasons. And his hopes for a future post-capitalist society were the opposite of Soviet authoritarianism. He wanted to extend democracy from the political sphere to the factory floor through collective ownership and democratic control of the means of production by the workers themselves.

Nor did Marx think that socialism could come about in a semi-feudal country like Russia in 1917. A big difference between Marxism and earlier forms of socialist thought is that Marx thought capitalism wasn’t an avoidable historical mistake but a necessary stage of historical development. It builds up the economic machine of society to a point that makes a more democratic and egalitarian system possible without everyone being reduced to sharing a few crumbs and an authoritarian government keeping people in line. He was very clear that unless a revolution in Russia was accompanied by revolution in the industrialized West, there was no way Russia could skip from a pre-capitalist country to a flourishing socialism.

Russian President Vladimir Putin is seen on a screen set at Red Square as he addresses a rally and a concert marking the annexation of four regions of Ukraine Russian troops occupy - Lugansk, Donetsk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, in central Moscow on September 30, 2022.

Alexander Nemenov/AFP via Getty ImagesIn a couple of writings when thinking about a transition to socialism, Marx briefly uses the phrase “the dictatorship of the proletariat.” But, in context, this widely-misunderstood phrase means not the dictatorship of a single individual or a single political party, but the rule of the proletariat—i.e. of the working-class majority of society.

Marx’s model for what such a proletarian “dictatorship” might look like was the Paris Commune of 1871—when ordinary workers and soldiers briefly took over the city government in Paris at the end of the Franco-Russian War. In his pamphlet, The Civil War in France, the specific features of the Commune he singled out for praise were radically democratic ones—like making all elected officials recallable by their constituents at any time and for any reason, and limiting them to the average salary of a skilled worker.

Speaking of the Franco-Prussian War, here’s what Marx wrote about the beginning of that war:

“The English working class stretch the hand of fellowship to the French and German working people. They feel deeply convinced that whatever turn the impending horrid war may take, the alliance of the working classes of all countries will ultimately kill war.”

In other words, working-class people everywhere are used as cannon fodder in wars they have no say in starting. It’s in their interests to join together across national boundaries to “kill war.”

Who do you think the author of that quote would have identified with more—Russian and Ukrainian draft resisters desperate not to have their lives thrown away in the conflict, or the conservative nationalist politician, supported by wealthy oligarchs and the Russian Orthodox Church, who started the war?

It’s not a hard question.