In the two decades that James “Whitey” Bulger served as a secret FBI informant while extorting citizens, peddling cocaine, and killing people to protect his Boston-based criminal empire, there is only one federal agent who tried seriously to shut him down: Robert Fitzpatrick.

For his efforts, Fitzpatrick was frustrated at every turn, not by Bulger and his fellow gangsters, but by his own, the FBI.

After being introduced to Bulger in 1981, Fitzpatrick warned his regional supervisor that Whitey was “sociopathic … untrustworthy … likely to commit violence” and suggested that he be “closed” as an informant. Not only were his memos and recommendations ignored, some in the FBI sought to discredit Fitzpatrick and destroy his reputation.

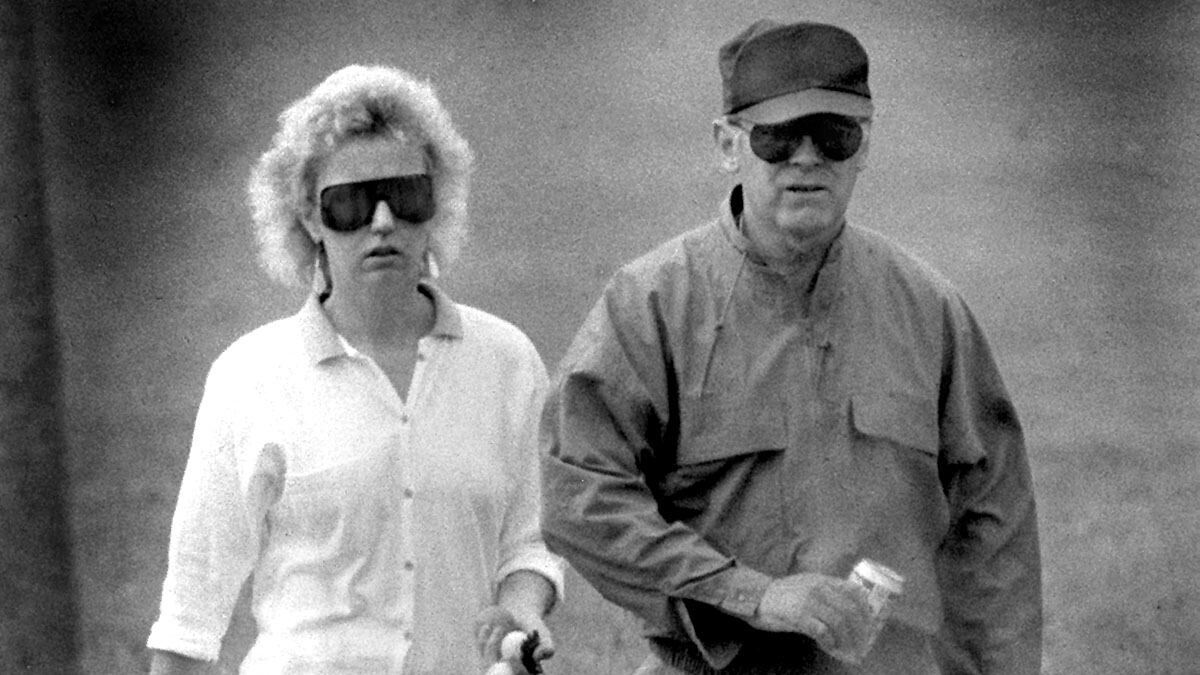

The aggrieved former G-man finally has the opportunity to tell his side of the story in Betrayal, an explosive memoir of his years as assistant special agent in charge of the FBI’s Boston office. The book has the feel of an ongoing therapy session, as Fitzpatrick seeks to make sense of a sprawling conspiracy of agents, cops, judges, criminals, and politicians who for decades enabled Bulger and made it possible for his campaign of corruption and terror to infect an entire city. Currently, Bulger awaits trial on 19 counts of murder, after having been on the lam for 16 years.

It is a sickening story, one that Fitzpatrick and his co-author, Jon Land, allow to unfold slowly, like a toxic oil spill that envelopes and destroys the surrounding ecosystem—in this case, the entire criminal justice system of the state of Massachusetts.

It is now common knowledge that Special Agent John Connolly, Bulger’s primary handler in the Bureau who is presently in prison on murder charges, and former state senator William “Billy” Bulger, Whitey’s powerful politician brother, formed a support system that made it possible for the Bulger era to sustain itself. But in Betrayal, Fitzpatrick broadens the conspiracy, detailing the culpability of a vast matrix of enablers, including, most notably, the late Jeremiah T. O’Sullivan, who, as lead prosecutor for the state’s Organized Crime Strike Force, undermined potential prosecutions of both Whitey and Billy Bulger, and Lawrence Sarhatt and James Greenleaf, successive special agents in charge of the FBI’s Boston office, who buried reports, including Fitzpatrick’s recommendation that Bulger be “closed” as an informant.

Fitzpatrick does not attempt to portray himself as a hero; the dominant tone of the book is one of frustration and astonishment as the author, who was sent to Boston by FBI headquarters in Washington D.C. with the expressed task of evaluating Bulger’s “suitability” as a top-echelon informant, encounters malfeasance and corruption at every level.

Early in the book, he describes being a young boy at the infamous Mount Loretto orphanage in Staten Island, N.Y., where he encountered bullies and institutional abuse. Late at night, he sought solace by laying in the dark and listening to the popular radio program This Is Your FBI. Fitzpatrick’s belief in the FBI as both an avenue of personal salvation and an institutional force for justice haunts the book, as the reality of corruption and careerism crushes his idealism much the same way Bulger strangled, shot, and mutilated his murder victims.

Fitzpatrick came to Boston well suited to deal with subterfuge and corruption. He had gone undercover in the Deep South in the mid-Sixties in an attempt to penetrate and bring down white supremacist organizations. In the 1970s he’d been one of the lead agents on the ABSCAM investigation, a sting operation involving corrupt public officials that led to numerous high-profile arrests, including the indictment of a sitting U.S. senator.

In Boston, Fitzpatrick spent nearly a decade trying to unravel what he calls “the Bulger arrangement.” As a veteran G-man who had trained budding agents on the proper cultivation of criminal informants at the FBI academy in Quantico, VA, he recognized all the telltale signs of a disaster in the making. He saw that Connolly and his supervisor, John Morris, were too close to Bulger. Also, as Fitzpatrick noted to anyone who would listen, the Bulger situation violated one of the most basic tenets of informant cultivation; the proper strategy with informants is to get someone mid-level who can help take down the boss and therefore an entire organization. You cannot have an organized crime kingpin as an informant, because it is inevitable that person will choose to manipulate the information they reveal to their handlers as a way of staying in power.

When it became apparent to Fitzpatrick that his warnings about the Bulger relationship were being ignored, he sought to build his own cases against the mob boss. He developed informants like Brian Halloran, a sad-sack career thug who worked for Bulger, and John McIntyre, a naïve Irish Republican Army (IRA) sympathizer who partnered with Bulger on a scheme to send guns to Northern Ireland in exchange for shipments of marijuana and cocaine. Agents in Fitzpatrick’s own office leaked information to Bulger about the informants; Halloran and McIntyre were both brutally murdered by Bulger, as were other informants whose identities were compromised and revealed to local gangsters by Connolly and Morris.

In the end, Fitzpatrick’s reputation within the Bureau as a potential whistleblower and general “pain in the ass” began to wear him down. It took a personal toll on him and his wife. Fitzpatrick began to get the sense that Bulger and his gangster partner Steve Flemmi, who was also a longtime FBI informant, were more important to the local office than he was. “Apparently Bulger and Flemmi were the FBI’s ‘guys’ while I, somehow, wasn’t,” writes Fitzpatrick. “While busting [the Mafia] remained every bit a top priority in Washington, my efforts and accomplishments were being demeaned by a groupthink mentality that led to a scenario of ‘us versus them,’ with me inexplicably linked with ‘them.’”

When Fitzpatrick, frustrated and disillusioned, resigned from the Bureau in 1987, the full dimensions of Bulger’s partnership with the FBI was not yet known, even to the agent. It wasn’t until the late 1990s, when Bulger went on the lam after being tipped off by his FBI contacts that he was about to be arrested, that the truth started to come out. In a series of hearings and depositions, the Bulger cohorts who were left behind turned “rat” and testified in court. In a groundbreaking hearing presided over by Federal Judge Mark Wolf, Fitzpatrick testified, and for the first time the story of his efforts to rectify the Bureau’s sinister alliance with Bulger began to take shape.

In January 2000, after Whitey’s righthand man provided details on a series of murders, including where the bodies were buried, Fitzpatrick stood in the rain alongside Dorchester gulley as the remains of John McIntyre, his one-time informant, were dug up. “As I stood on that embankment,” writes Fitzpatrick, “steaming over confirmation of what I’d suspected ever since John McIntyre had disappeared in 1984, I never imagined I was looking at the means to achieve my long sought vindication.”

Fitzpatrick’s vindication would come in court, where he testified as part of a civil lawsuit brought by the McIntyre family—and other families of Bulger’s victims—against the FBI and the U.S. government for having underwritten Bulger’s murderous criminal career. In 2006, the McIntyre family was awarded $3.1 million in damages. All told, litigation from cases related to the Bulger debacle would result in damages of more than $20 million.

Betrayal provides the most complete overview to date of the culture of corruption that made Bulger possible. Fitzpatrick names names and offers an appendix filled with FBI memos, letters, and excerpts from depositions and court proceedings. The cumulative effect is a devastating reaffirmation of the findings of a U.S. congressional committee that declared the Bulger-FBI relationship to represent “one of the greatest failures in the history of federal law enforcement.”

The final chapter on Bulger has not yet been written. Whitey is scheduled to stand trial sometime in 2012, and Fitzpatrick will likely be called to testify. In this sordid saga of homicidal gangsters and dirty federal agents, Fitzpatrick’s perspective—and his book—offers a rare beacon of light.