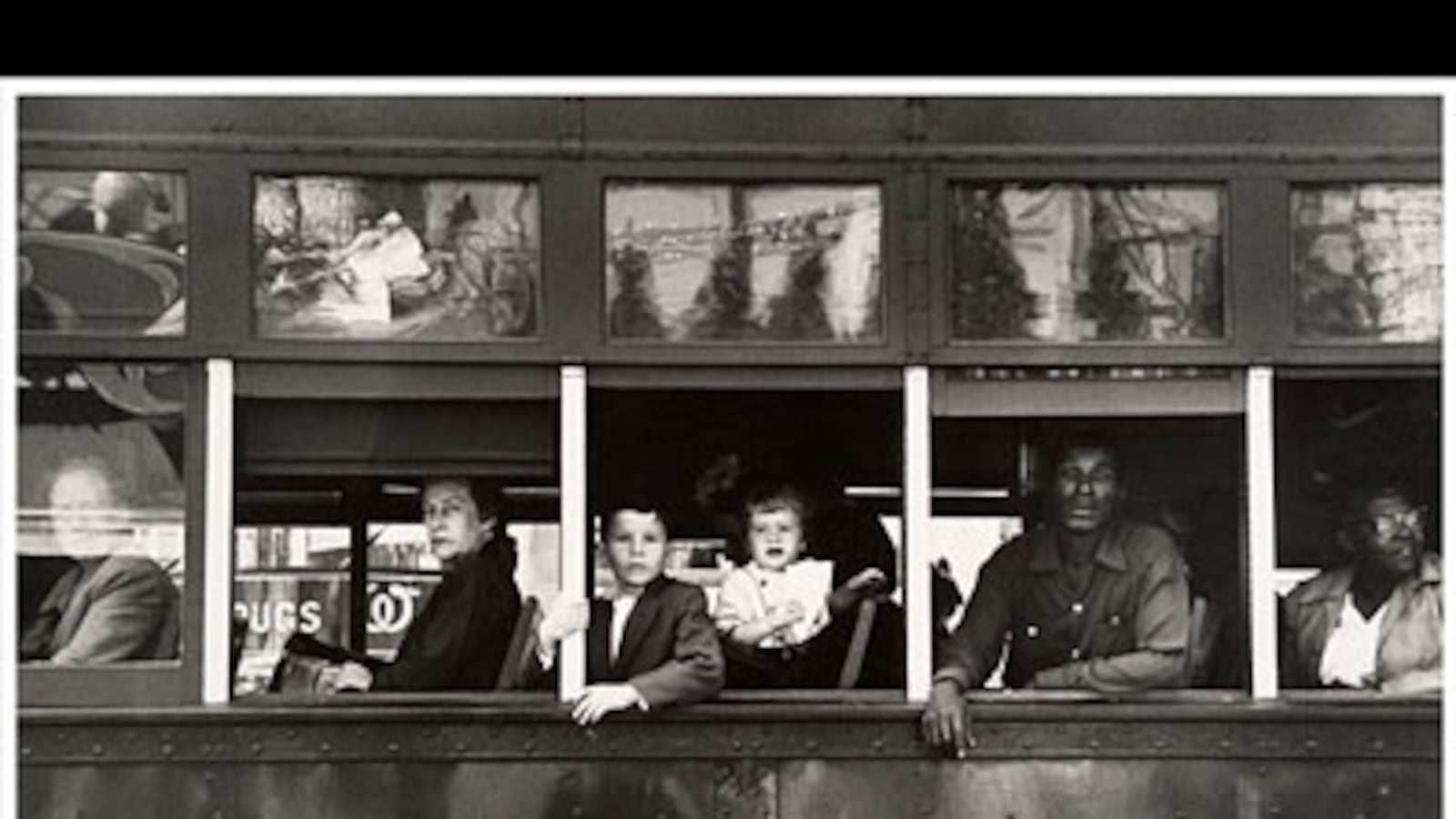

In 1959, the Swiss-born Robert Frank published a modest book of black and white photographs. His pictures were made during several road trips across America in the 1950s and show common people in ordinary situations. They were dismissed at the time, not only for their “muddy exposures, drunken horizons, and general sloppiness,” but because they were perceived as a bitter indictment of American society.

Still, his fellow photographers recognized the tenor of their moment reflected in his work, and the book, The Americans, has long since come to be regarded as a 20th-century masterpiece.

Click Image Below to View Our Gallery

Now Frank, arguably the most influential living photographer, is about to mark another defining cultural moment. Next week, the exhibition, Looking In: Robert Frank’s ‘The Americans, opens at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That august institution has never before given such comprehensive focus to a single body of work by an individual photographer—nor has it bestowed such a crowning acknowledgment of photographic achievement.

All 83 pictures from The Americans will be exhibited together for the first time in New York. Additionally, the show, organized by Sarah Greenough, a senior curator at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., where it originated last January, includes vintage contact sheets from which the pictures were selected (out of 767 rolls of film); a wall of the original work prints from which Frank selected the final images for the book; a map that charts his cross-country trips; correspondence that includes letters to Walker Evans; and Jack Kerouac’s original typescript for the book’s introduction. As exhibitions go, this one strikes a remarkable balance of incisive, exhaustive scholarship and rich visceral satisfaction.

The show features a map that charts his cross-country trips; correspondence that includes letters to Walker Evans; and Jack Kerouac’s original typescript for the book’s introduction.

Until Robert Frank came along, objectivity was a hallmark of the documentary photograph, typified by the compositional tidiness, visual clarity, and emotional distance found in the work of Walker Evans. Not only did Frank’s photographs liberate the picture frame from those conventions, his work has come to underscore the idea that what passes for photographic objectivity may be only a matter of style. Frank set out to document America, but he made a visual chronicle of his own experience at the same time.

Abstract Expressionism defined the artistic climate in which the photographs for The Americans were produced. Frank, who lived in downtown Manhattan from the time he arrived in the United States in 1947, counted among his good friends Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Allen Ginsberg. They set a precedent for Beat generation artists and writers, whose improvisational art-making practices aimed for the spontaneous act of expression to be a vital component of their work. Frank’s pictures reflect the stream of consciousness art making of the period as he attempted to capture the authenticity of his own experience in visual terms.

Frank might well be called the father of “the snapshot aesthetic,” a term coined a decade after The Americans was published to identify an emergent photographic style that combined the un-self-conscious informality of family snapshots, the authenticity of documentary photography, and the increasingly active style of news pictures. “Innocence is the quintessence of the snapshot,” Lisette Model would write. “I wish to distinguish between innocence and ignorance. Innocence is one of the highest forms of being and ignorance one of the lowest.”

A fidelity to the spontaneous moment is no longer the terra firma on which the photographic image is grounded. The constructed narrative has come to dominate the landscape of contemporary photography. Today’s wall-size, color saturated, commercially hued, and issue-infused photography casts Frank’s modest black and white pictures in poetic relief. They look so pure and true by comparison, and it is quaint to think that they were perceived as blurry and badly composed when they were made. They seemed more in keeping with the grainy look of early broadcast-television imagery. Nonetheless, Frank’s pictures might have appeared bleak and disparaging in context of the breezy veneer of American optimism and affluence promoted in movies and glossy magazines of that period, but, contrary to what people thought, he was on something of a romantic quest to find what was true and redeeming about his adopted country.

Frank set out to make a photographic chronicle of America that wasn’t simply to take one picture at a time; it was a larger endeavor to put a book together the way he thought it should be—one picture per page, identified only by the name of the place it was taken and the date. There is a poetic register to Frank’s pictures in The Americans, not only in the actual moments he captured but, also, in the quality of his own experience resonating in the frame.

Plus: Check out Art Beast, for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Philip Gefter was a picture editor at The New York Times and wrote regularly about photography for the paper. His book of essays, Photography After Frank, was recently published by Aperture. He is currently producing a feature-length documentary on Bill Cunningham of the Times, and working on a biography of Sam Wagstaff.