Mitt Romney’s brazen attitude toward Bain Capital’s dealings in Panama, coupled with his refusal to release his tax returns, shows he is more than out of touch with the causes of the men and women he would serve. He is openly at odds with their financial well-being. How is it that someone can talk relatively openly about having potentially taxable income parked overseas and remain a viable candidate for the highest public office? How often, really, do places with lax banking regulations such as Liechtenstein, or Andorra, or Switzerland enter our national dialogue?

Offshore tax evasion presents an especially insidious example of our “out of sight, out of mind” mentality about how our financial systems operate at the highest levels. As international banking has become an increasingly mystical and mystifying process, we have lost sight of how what one individual does with his income—say, moving it to the Cayman Islands—directly influences our own lives.

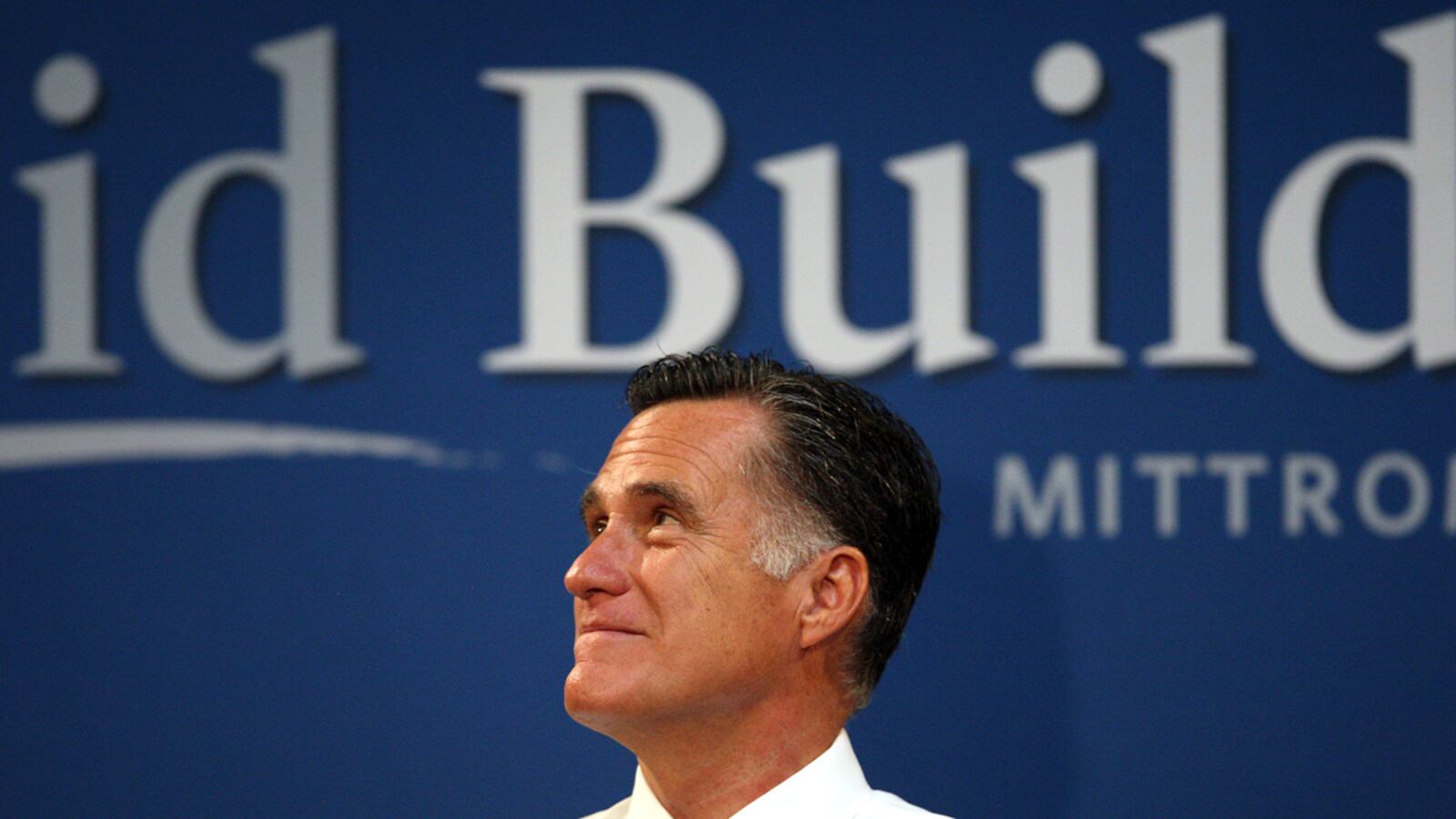

Which is precisely why, when Robert Costa of National Review asked the Republican candidate why he had yet to rid himself of the offshore accounts that were providing such easy fodder for his opponent, Romney’s best defense was to hide behind the cloak of obscurantism. He informed Costa, as one might a schoolchild, that “the world of finance is not as simple as some would have you believe.” Employing a disingenuous double logic, Romney worked hard to present a convincing argument that offshore accounts benefit America. “The so-called offshore account in the Cayman Islands, for instance, is an account established by a U.S. firm to allow foreign investors to invest in U.S. enterprises and not be subject to taxes outside of their own jurisdiction,” he said. “So in many instances, the investments in something of that nature are brought back into the United States.”

International finance is indeed a complex system, which is why specialized firms such as Bain Capital charge as much as they do. As markets become increasingly interconnected, allowing vast sums of money to move about the globe in real time, there are ever more complicated schemes through which individuals can secret money away from their home nations.

But when all of those individual offshore accounts are considered as a whole, they present a resoundingly clear and alarming picture. All of that potentially taxable income sitting in tax havens amounts to billions—some estimates say trillions—of dollars lost from the American tax pool. For local communities, this translates into a host of government services and programs that won’t be launched because the revenue that would have funded them has been lost forever.

We need to stop thinking, or not thinking, about tax havens as peripheral spaces with little influence on our economy. A group of economists led by Columbia University’s Ronen Palan has proposed that tax havens are “one of the most important instruments in the contemporary globalized financial system” and “one of the principal causes of financial instability.” The more money that moves about in territories with lax banking regulations, the more opaque and thus unstable our own financial institutions become.

Meanwhile, the territories complicit in these kinds of clandestine banking operations profit wildly from money that would ideally benefit the home nations of the clientele they serve. Monaco, for instance, boasts a GDP estimated at more than $6 billion despite having a population of roughly 30,000 and a territory spanning less than half the size of Central Park. A French government report on Monaco’s banking system, released in 2000, found that there were roughly 10 bank accounts for every one resident, with the bulk of these accounts held by absentees. The same report quotes the principality’s head of foreign relations as saying that for Monaco to operate as a relatively tax-free environment “a certain equilibrium must be respected. We cannot allow ourselves the luxury of frightening people. Launching a financial inquisition of dubious merit would promote bad feeling all around…because the majority of foreigners here have made their mea culpa in their countries of origin and come here in peace.”

In the decade since that report appeared, Monaco has tried to appease the international community by tightening regulations. But what about other territories that are less compliant? Whose job is it to keep the snakes out of these fiscal paradises? We cannot depend on wealthy individuals with few real ties to the places in which their money is deposited to take an active interest in the dirty politics or potential ties to money laundering and terrorism found in such states. Nor can we logically expect the foreign governments reaping so much reward from this absentee population to self-regulate.

We need to take responsibility locally for the ways our money moves about internationally. It is unpleasant to think that, in certain circles, if a person mentioned having an account in the Caymans, he or she would more likely be asked to recommend a good tax lawyer or the best restaurant in the Caribbean than be branded a traitor.

When pressed by Costa about his offshore financial wrangling, Romney made sure to remind voters that all of his investments are managed “in a blind trust.” When someone running for public office acquires and invests wealth in a manner that has potentially negative consequences for his fellow taxpayers, we need to open our eyes and take a long and sober look at the numbers. They will tell us a story far simpler than some would have us think.