It could’ve happened to any black man. This sort of thing happens all the time. But this particular instance—legendary Harvard professor Henry Louis “Skip” Gates, Jr., arrested on his own front porch—tells you that even if a black man is a brilliant, famous, rich, classy, Harvard professor who’s 58 years old, walking with a cane because of hip-replacement surgery, and ensconced in his own Cambridge home during the day, he can still be arrested.

After the arrest of Skip Gates, the most important black academic in the country, we can put all that kumbaya we’re-post-racial crap in the toilet.

That’s because Malcolm X’s 40-year-old quote is still true: “What do you call a black man with a Ph.D.? A nigger.”

Some people were thinking, “We’ve got a black president, America is beyond racism, we’re post racial now.” Some think racism has become a boogie monster that only blacks fear is under the bed, but there’s nothing but paranoia.

Well, after the arrest of Skip Gates, the director of Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, the most important black academic in the country, we can put all that kumbaya we’re-post-racial crap in the toilet.

In the hours after the story broke, the actor/playwright Sarah Jones tweeted, “Do we still need our Free Papers?” Yes, the incident sent shock waves so deep that people felt echoes of being post-slaves and having to prove their liberty to anyone who asked. Gates told me in an email, “I am outraged.” Many are.

Being a black man is often Kafkaesque, and this situation definitely is. The facts agreed upon by the Cambridge Police Department’s report and the statement released by Harvard Law professor Charles Ogletree, who’s serving as Gates’ counsel, are these: On Thursday, July 16, 2009, around 12:44 p.m., Gates forced open the door to his Cambridge home. Someone called 911 to report breaking and entering. An officer approached Gates’ home, when Gates was inside, and asked him to step outside. Gates declined. The officer went into Gates’ home, where Gates showed him ID that proved Gates lived there. Gates asked for officer’s name and badge number and Gates did not get them.

Gates was handcuffed on his own front porch, where several officers had amassed. He was charged with disorderly conduct and taken to the Cambridge Police Station, where he spent four hours locked up. Those are the points of agreement, but the differences between the two accounts are so many they suggest two entirely different sets of people interacting.

The police account paints Gates as belligerent and tumultuous from the encounter’s beginning, while the officer is polite and accommodating in the face of an unruly person. A neighbor sees a man breaking into a home and calls 911. When an officer shows up at Gates’ home he says he’s investigating a break-in in progress and Gates responds, “Why, because I’m a black man in America?”

Gates arrogantly berates the officers, his mouth never stopping, telling the officer that he has no idea who he is messing with and that he’s racist. When the officer asks Gates to step outside, Gates says, “I’ll speak with your mama outside.”

Still, there is this sentence: “While I was led to believe that Gates was lawfully in the residence, I was quite surprised and confused with the behavior he exhibited toward me.” That’s so precious—the officer has entered a man’s own home and asked him if he’d broken into it and asked him to prove that it’s his home and still is confused about why the man is angry.

Gates’ account, as presented by Ogletree, paints Gates as a gentleman while the officer is strangely quiet. Gates had just returned from a trip to China, where he was shooting his new PBS documentary. The door was broken and needed to be forced open. Shortly afterward, an officer arrived and Gates told him who he is and provided ID. But when the officer walked out of Gates’ house, saying nothing, Gates followed him, asking fruitlessly for his badge number.

The officer said, “Thank you for accommodating my earlier request,” meaning to come outside, and then, for no apparent reason, placed Gates under arrest, handcuffing him on his own front porch. There must be more to both stories.

This is surely not over—there’s a gulf between those two accounts wide enough to drive a Hummer through. And many questions are left unanswered: Why did Gates’ neighbor, who works at Harvard magazine, fail to recognize him? When the Harvard University Police showed up, couldn’t they have realized what was happening and whose home it was and found another way to resolve all this? And most important, why did the officers find it necessary to arrest a man who was in his own home and who had not posed or made a threat to them? The worst crime in the police report is Gates yelling at an officer who was telling him to calm down. Is that a crime?

Skip Gates has long been an extraordinary figure, but it’s more than his stature, it’s that the incident happened in his home that makes it a frightening, tragicomic moment worthy of Chappelle’s Show. Black intellectual who’s navigated his way up the ladder to the top of academia but suddenly can’t handle a cop asking rude questions. Comedian Paul Mooney jokes about certain blacks having something horrible happen to them that serves as their “nigger wakeup call,” as in, a reminder that no matter their money or status, being black will eventually catch up with them. This time I think we all got a nigger wakeup call.

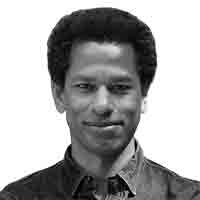

Touré is a columnist for The Daily Beast. He's also an NBC contributor and the author of Never Drank the Kool-Aid , Soul City , and The Portable Promised Land . He is a contributing editor at Rolling Stone, was CNN's first pop culture correspondent, and was the host of MTV2's Spoke N Heard . His writing has appeared in the New Yorker and the New York Times.