It may be hard to fathom today, but there was a time when the existence of a 23-inch-long satellite heralded America’s downfall. The tiny contraption in question was Sputnik, the launching of which by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957 simultaneously set off the “space race” between the United States and its communist adversary. That Moscow had beaten the US into space cast a pall over the nation; one commentator noted Sputnik was “a shock which hit many people as hard as Pearl Harbor.”

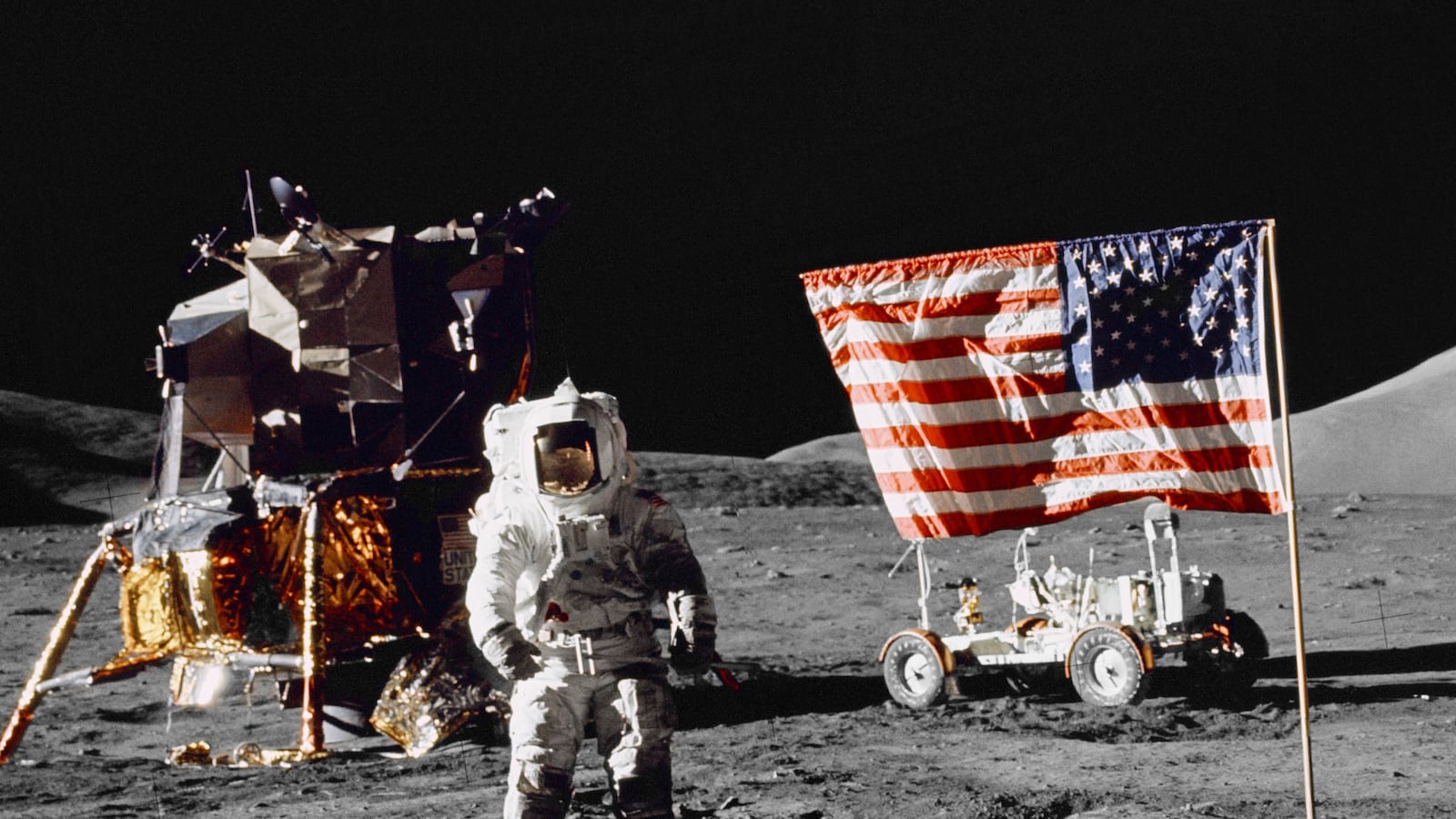

Of course, 12 years later, America landed the first man on the moon, which, like Sputnik before it, was a momentous if largely symbolic achievement. But it hardly dissuaded the prophets of American decline, whom, according to German intellectual Josef Joffe, have been repeating a similar mantra, carefully adapted to the times, since the founding of the American republic. The specific markers of the country’s deterioration may change with the era, but the message is the same: America, once a great and mighty power, will soon be dislodged from its place as #1, a state of affairs owing both to self-inflicted wounds and the inevitable “rise of the rest.” A consistent theme in the diagnosis is that it is precisely America’s distinguishing characteristics—its placing a high value on individualism and what appears to many as a free market fundamentalism—will ultimately lead to the country’s downfall. “Capitalism is the threat and America its vanguard,” Joffe writes of declinists then and now. “This motif has been a classic of anti-modernism for two centuries in Europe.”

Joffe, editor-publisher of the highly influential German newspaper Die Zeit, is a longtime observer of America, having been educated here as a young man and a long-time teacher at Stanford. First arriving at Swarthmore as a student in the 1960’s, he speaks from experience when he writes that America’s supposed, “decline unfolded not over centuries, as in the case of Rome, but as repertoire theater season by season.” His new book, The Myth of America’s Decline: Politics, Economics and a Half Century of False Prophecies, provides a much-needed response to the trendy “declinism” that has become a cottage industry among pundits like Fareed Zakaria, who heralds the “post-American world,” and Thomas Friedman, who has never encountered a Chinese high speed rail project or shopping mall he didn’t think spelled the end of America’s global preeminence.

Hardly an uncritical cheerleader of The American Way, Joffe is nonetheless rare in being a European commentator who does not revel in the easy anti-Americanism embraced by so many of his colleagues. Most of his book is comprised of hard data analysis that might come as a surprise to those of us treated to endless forecasts of America’s imminent demise. To be sure, Joffe concedes that there is “always a rational basis for this kind of angst attack” that has perpetually afflicted American pessimists. It wasn’t just Sputnik that made so many fearful about their country’s future; that year the US economy shrunk by 4%. Similarly, the economy witnessed a 5% drop in 2008, the beginning of the global financial crisis. What’s remarkable, however, is that America has always—always—bounced back. Its share of the world economy was 27% in 1950, a figure that has remained consistent to the present day. Meanwhile, China’s rise, while impressive, is only so remarkable because of the low point at which the country began its economic ascent, and it remains a place where literally hundreds of millions of people continue to live in poverty. Indeed, the gap between American and Chinese GDP has actually widened since 1990, not closed.

America has also been able to endure the sorts of military and economic setbacks that have cast asunder countless empires before it. The Vietnam War, though traumatic to the nation at home, did not spell an end to America’s global power (while the Soviet Union’s Vietnam, an ill-fated adventure in Afghanistan, precipitated its dissolution). Joffe points out that no country today would be able to launch two, massive, overseas land wars—as America has done in the past decade in Afghanistan and Iraq—never mind maintain its pride of place after achieving stalemates, at best, in both conflicts. Though President Obama’s defense cuts have come in for criticism, America still boasts a navy whose tonnage is larger than that of the next 13 largest navies combined, a figure that will not change despite a massive Russian military modernization plan and China’s expanding naval capability. The thesis of “imperial overstretch,” which forecasts that America will suffer the same fate as the British Empire due to its overseas military commitments, has hardly come to fruition.

Meanwhile, Joffe throws some much-needed cold water on the China boosters endlessly wowed by Beijing’s model of politically authoritarian, managed capitalism. Dredging up historical examples across the world, Joffe shows how economic “growth favors democratization,” as a widening middle class expects more political accountability from its leaders, yet as “democracy expands, growth shrinks.” So China will face a choice: either increase democratic rights and experience slower growth, or clamp down even harder on the populace, thereby risking “a Tiananmen and its twin, a crashing economy.” The Chinese “three C’s,” as Joffe dubs them, “crony capitalism, corruption and collusion,” are a recipe for disaster. China’s moment in the sun, then, is temporary, and its rapidly aging population—thanks in no small part to the one-child policy—means the massive bill will come sooner rather than later.

Numbers, however, only tell us so much. While acknowledging that anything is possible and America’s best days may yet be behind us, Joffe is adept at explaining the intangible factors that will likely ensure America’s preeminence for ages to come. In the wake of the financial crisis and domestic political deadlock, many Americans have pointed towards China’s authoritarian capitalism, in which pesky things like democracy and free speech don’t get in the way of grand infrastructural projects, as a better alternative. Yet it is precisely the ingredients of America’s open society—however messy and ineffective it can at times seem—which have guaranteed the country’s success. China’s highly managed economy and authoritarian educational system discourages entrepreneurship and independent thinking, what Joffe believes to be America’s most enduring and important qualities. As a “universal nation” founded and continually replenished by immigrants, America is unique in not connecting nationality to blood and soil, making it the most welcoming place in the world for immigrants, who continually invigorate the American economy.

In conclusion, Joffe moves from an analytical repudiation of the declinists to a reasoned, unemotional argument detailing why a world without American political, economic and cultural leadership would be an objectively bad thing. For all the cries over so-called American imperialism, America is a “liberal empire” in the mold of its British predecessor; it “fought three very large wars (one cold) a la Britain—not to overturn but to restore the balance.” America is a status quo power, the “default power,” Joffe writes, because it performs the heavy lifting of maintaining a liberal, rules-based world order that no other one nation or even concert of nations is willing, never mind capable, of doing.