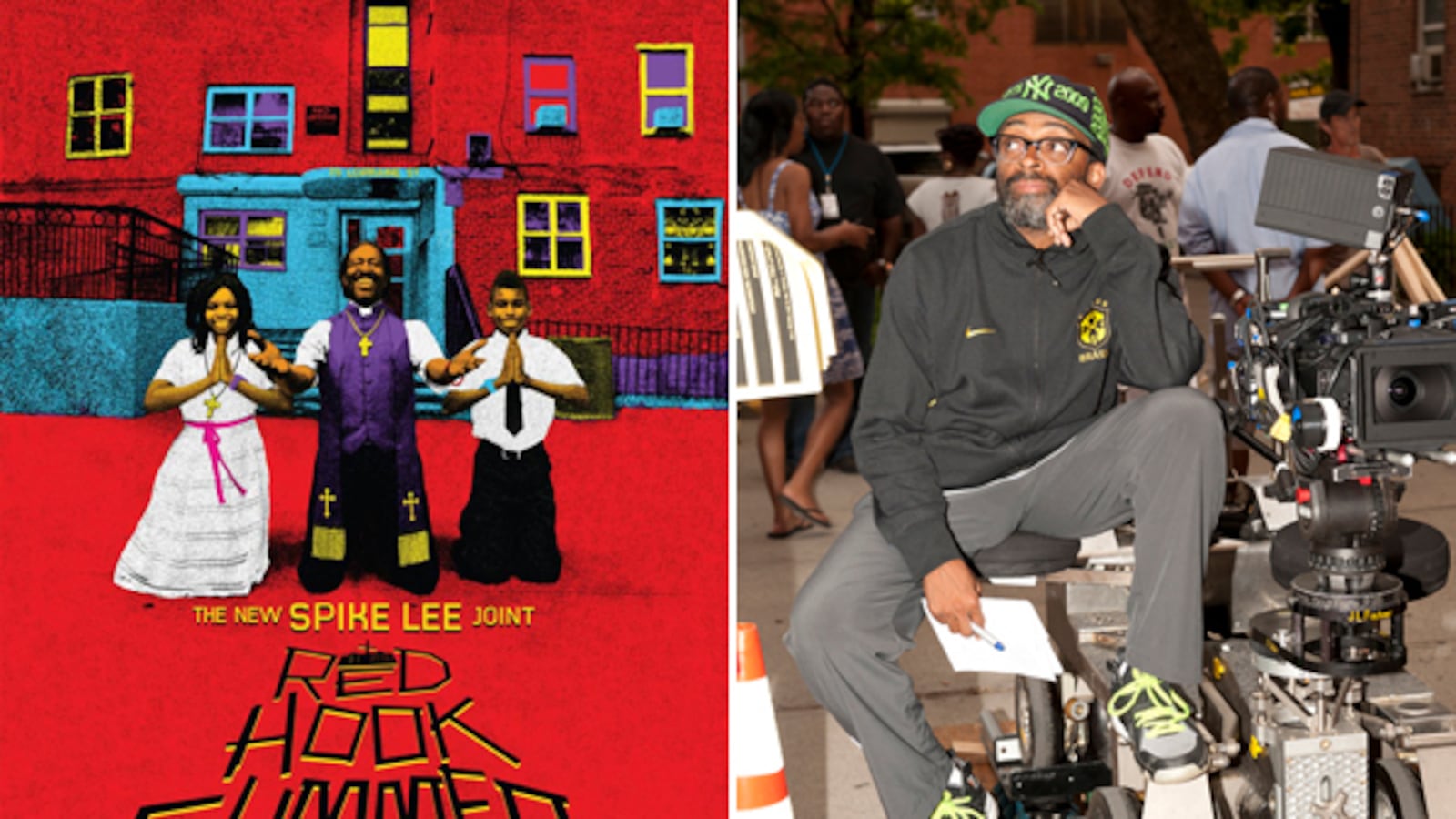

Director Spike Lee has two teenage children of his own and he’d like for you to get to know them—or at the very least, realize teenagers just like them actually exist. In his new film, Red Hook Summer, Lee and his cowriter James McBride attempt to lure moviegoers into the lives of two average African-American teenagers growing up in Brooklyn and learning the heavy lessons of friendship, love, pain, and redemption during one hot summer in a Red Hook housing project.

Lee tells the story through the eyes of Flik Royale, a determined young boy sent from his middle-class home in Atlanta to live with his ultrareligious grandfather in New York. The cultural shift and the haunting family secret that is eventually revealed in grand fashion should keep audiences completely tuned in, engaged, and shocked. Of course, the 55-year-old filmmaker is no stranger to controversy or in making films that showcase a different slice of African-American life. His hometown of Brooklyn is the stirring backdrop to a fascinating study on teenage angst, strained family relations, and the loving communion found every Sunday morning in the black church. Lee, the father of a daughter and son, was so committed to getting Red Hook Summer in theaters that he financed the movie himself. Tomorrow, after a strong showing in New York last week, the film will open in Los Angeles and other major cities via the self-distribution specialist Variance Films. Lee spoke with The Daily Beast about his own faith, Willow and Jaden Smith, and the 2012 presidential election.

Why was making this type of film with such a strong religious backstory so important to you?

Lee: Well, first off we didn’t begin thinking it would be a film about the black church. In conversations with different people like James McBride (author of The Color of Water), we were always talking about our teenage kids and what they were like and what they were doing. Then we’d talk about not seeing teenage kids like ours on the big screen. That’s where Red Hook came from and that’s why I was OK paying for it to make sure it was released.

You weren’t seeing kids like yours in the mainstream media and thought that was a huge problem in 2012?

Yes. I love those films by Rob Reiner about teenagers like Stand by Me. Those were great films about being teenagers, but there weren’t ever films about black teenagers like that and I asked myself why. I kept thinking where are those films that show black teenagers like my kids, James’s kids, and others’ kids who aren’t gangstas, thugs, or whatever. Kids that are just teenagers living life and not in trouble. With the exception of Jada and Will’s (Smith) kids, where do you see regular black kids like that in media? You don’t. But they do exist and so Red Hook is about a few of those kids. Then we had to add layers and that’s where the black church came into play.

You said that you weren’t raised in the black church yet the church scenes are among the most stirring in the film. How did that happen?

James wrote some of those church scenes, and when we filmed them, they took a life of their own. People were really getting the spirit in the church and forgot the cameras in there. We had real gospel choirs with people from Spelman and Morehouse colleges singing. People were catching the holy ghost and we caught it all on the camera. We had people from everywhere in the church and they heard the message being preached by the good Bishop Enoch Rouse (actor Clarke Peters of The Wire) and connected. We were really able to capture great shots of call and response in the black church and that I think that resonates with audiences.

Is there a message in the film about the power and importance of the black church given the place it’s had in the community for years?

On some level, because so much history, so many great people and events have come out of the black church. We make the point in the film that this generation doesn’t go to church anymore or as much as the generation before them. That relationship isn’t there in the same way and that’s not just in the black church. That’s way it is for churches across the board no matter the color or religion, but for African Americans it could have a deeper meaning because of the history.

Were you moved to attend church at all by filming those scenes? It was hard not to "feel the spirit"’ in a few of those church scenes.

(Laughs) No. Every year I go with my wife to her parents’ hometown and attend church with them. It’s a homecoming service and that’s cool. We make that pilgrimage every year and that’s about it for me. It’s just not something I do particularly with the prosperity churches out here now. I don’t want to go to a megachurch where the Houston Rockets once played. It’s like waiting on Hakeem Olajuwon to come out or something during the sermon. I know church is a business, but now they aren’t “passing the plate’’—they’re passing the garbage cans around to take in a lot of money. It’s the mentality “I make thousands and thousands of dollars and so can you.” That’s church today. But people can worship the way they want. I’m not judging, just saying it’s not for me.

In a few of your last interviews about the film, you’ve made it clear that you aren’t the spokesperson for all black people on the issues. Is that a label people have placed unfairly on you? Does it bother you?

No. I accepted it after all these years, but on some programs, like Piers Morgan on CNN, I have to make that point because there can be confusion about that and a lot of questions with those expectations in the answers. I have to be clear on it.

You’re supporter of President Obama. You’ve said you never thought you’d live to see a day where we elected a black president. With that said, is this election more important than the last one?

I think so. We have to get him in for one more term. There isn’t the same excitement as it was for the last election but it will come. Sometimes [black people are] late as a people on some things, but it’s coming. Don’t worry.