Hillel International, the largest Jewish campus organization in the world, has long struggled with where to draw red lines on the conversation about Israel. Since the “Hillel Guidelines for Campus Israel Activity” were updated, there have been regular campus battles between university students and the organization. The guidelines restrict whom Hillel groups may partner with or host, based on their politics, something that has been persistently controversial. Yesterday, Swarthmore College Hillel took a huge step by breaking with the guidelines officially and declaring itself an “Open Hillel.” Now might be the time for Hillel International to take another stab at updating those guidelines.

The problematic bits in the guidelines that govern “Campus Israel Activity” include the following prohibitions on partnering with or hosting groups or speakers that as a matter of policy or practice: (a) deny the right of Israel to exist as a Jewish and democratic state with secure and recognized borders, (b) delegitimizes, demonizes, or applies a double standard to Israel, or (c) supports boycott off, divestment from, or sanctions against the State of Israel.

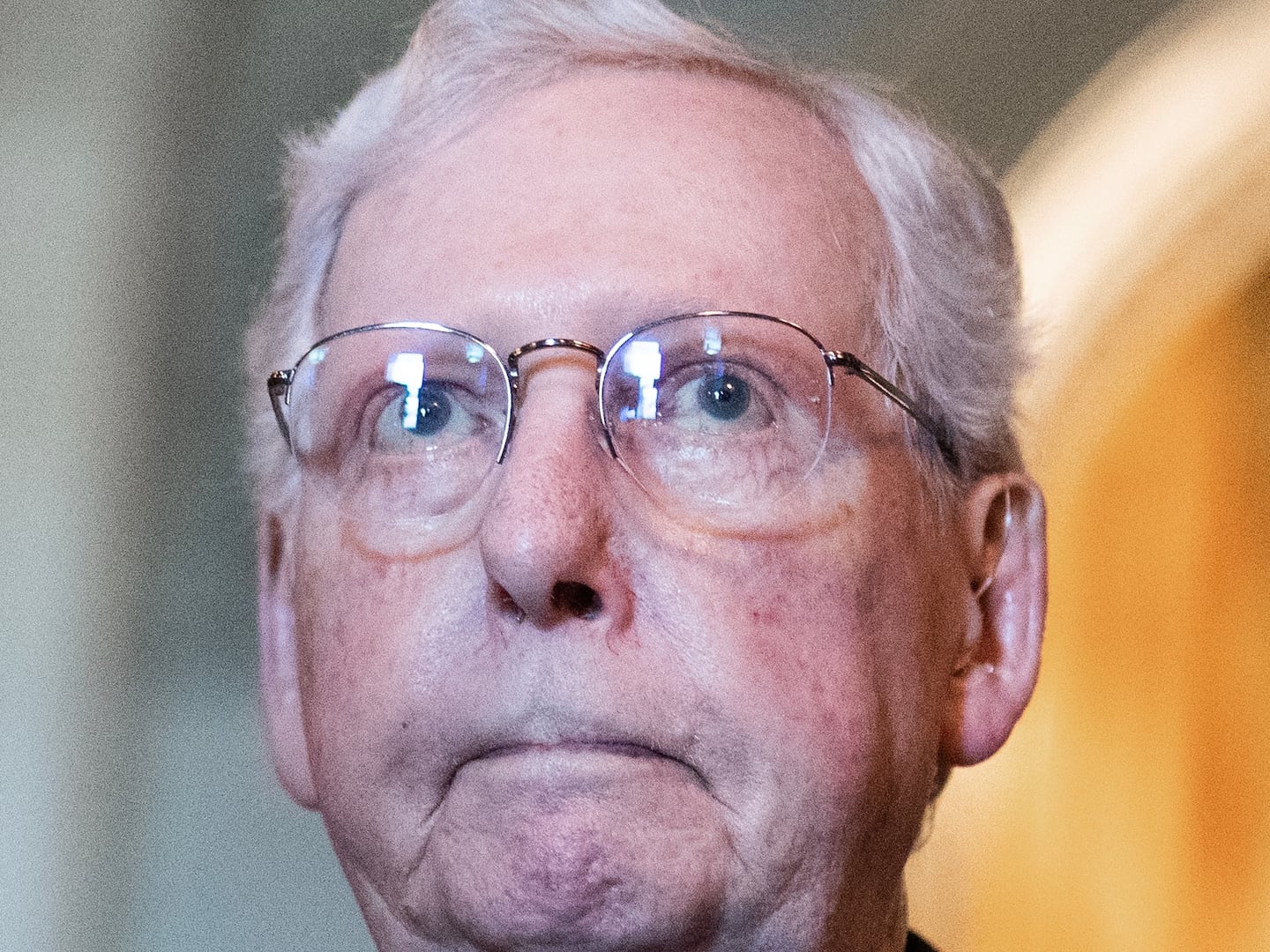

It is those bits that Swarthmore Hillel announced it is done with, and it’s those bits that have Hillel International President and former Democratic Ohio Congressman Eric Fingerhut up in arms. Those sections of the guidelines were emphasized when Fingerhut and long-time AIPAC leadership development director Jonathan Kessler teamed up in a recent op-ed in which they announced that they would work together “to strategically and proactively empower, train and prepare American Jewish students to be effective pro-Israel activists on and beyond the campus.” And it’s those prohibitions that spawned the initial Harvard-driven petition to “Open Hillel” which garnered nearly 900 signatures.

But Swarthmore didn’t need to break with these guidelines because it hasn’t been following them up until now. According to Swarthmore Hillel’s communications coordinator Joshua Wolfsun, for Swarthmore, this is “not a departure.” In fact, Swarthmore is in an “ideal situation”—both financially and structurally—to challenge the international organization with this bold move, Wolfsun told me. Swarthmore Hillel, unlike most in the U.S., does not have an executive board. Instead, it has only a “staff advisor” and students vote on Hillel decisions. Furthermore, it is not particularly reliant on Hillel International for funding.

In the last two years alone, Swarthmore has brought the often-fraught organization Breaking the Silence (BtS) without any trouble, applauded Noam Chomsky’s answers to questions on Judaism and Zionism (he pointed them to a Bible verse, though he didn't come to campus to speak on Israel-Palestine), and held a march for peace, co-sponsored by J Street U and Students for Peace and Justice in Palestine. Swarthmore is a liberal campus, and it’s been a liberal campus. Now they’re just letting us know.

So Swarthmore could do it, and they did it. But what about everybody else? Investigating the two cases Wolfsun pointed me to in our conversation—University of Pennsylvania Hillel’s experience with BtS and Harvard’s recent false step with former Knesset speaker Avrum Burg—we might not yet know the answer. Still, some introspection on the part of Hillel International might be worthwhile. Digging in its heels isn't getting it anywhere.

When I asked Leanne Gale, the principle student organizer for J Street U who brought BtS to UPenn’s campus last spring, whether she thought this could happen at Penn, her response was adamant: “Absolutely not,” she said. Gale had to jump through a million and one hoops to bring BtS, an organization of IDF veterans who talk about their experience serving in occupied territory, into the Hillel building. The reason being that BtS was a group that fit into one of the above-mentioned off-limits categories. Gale went to meeting after meeting to negotiate with the local Hillel Board of Directors and the Hillel Board of Greater Philadelphia (which is connected to the Jewish Federation). She even brought a petition and a letter signed by Jewish campus leadership, including the president and vice president of Hillel at the time, in an attempt to keep the event she had planned (and added to the Hillel calendar) at the very beginning of the year from being cancelled.

In the end, it was only postponed, but she was left with a number of stipulations: the event needed to be closed to the press, it needed to be framed as “pro-Israel” and was to be open to Penn students only. In the end, they held the event, turning away the reporter from Penn’s newspaper the Daily Pennsylvanian at the door and demanding Penn IDs from all entrants. Gale’s takeaway: “I think we fictitiously believe that Hillel is run by the students for the students,” she said. “In reality, Hillel is run by the money of Jewish Federations and big time alumni donors.” With an entrenched power system like Penn’s, Swarthmore-like chutzpah likely wouldn’t get very far.

I also spoke with Sandra Korn, vice-president of education for the Progressive Jewish Alliance (PJA) at Harvard. She told me how the Weatherhead Center for International Relations had reached out to her to see if she would like to bring Avrum Burg, whom they had already invited to campus, to speak at an event for students co-sponsored by Jewish and Palestinian groups. Like at Penn, she was told only once she scheduled the event—cosponsored by PJA, J Street, Harvard Students for Israel and Palestine Solidarity Committee (the Harvard equivalent of Students for Justice in Palestine)—that it could not be held inside the Hillel building, this time by Harvard Hillel’s executive director, who hadn’t realized when the event was scheduled that it would be cosponsored with a Palestinian group. This led to a great deal of running around until it was finally decided that there would be an event in Hillel with Burg sponsored only by PJA, and then afterwards everyone would trek across the street to hear Burg speak at the co-sponsored event.

“It wasn’t only an inconvenience to organize,” said Korn, “it was kind of embarrassing to have to explain to the Weatherhead Center why we weren’t having it in Hillel anymore…It put Hillel in a bad light, made Hillel seem petty. To the Center, this is a university, where people debate their opinions all the time.” When I asked Korn if she could see Harvard coming out with a document like Swarthmore’s, she said she didn’t know, either way, “Hillel International is going to have to change its idea of what’s acceptable in the campus Hillel because I don’t think Swarthmore is the only campus where Hillel students are open to hearing critical voices in their campus Jewish space.”

The official Hillel International response, published in a letter from Eric Fingerhut to Joshua Wolfsun, is genial enough at first, welcoming conversation. But it quickly becomes stern, announcing, “Hillel International does draw a line.” It restates the guidelines for good measure, and then is “very clear” that “‘anti-Zionists’ will not be permitted to speak using the Hillel name or under the Hillel roof, under any circumstances.”

Eric Fingerhut and Hillel International seem to have made a choice—they’re done. Swarthmore Hillel may need to take a new name (I suggest the obvious “Shammai”). But Penn and Harvard are not done. They have not yet burned the bridge Swarthmore has, but they are also not ready to let the conversation in their Hillel’s whither. Before this escalates any further, it might be worth all sides to consider a more local approach (as Harvard has begun doing) in which the circumstances of each college allow it to gather students who will—perhaps in conjunction with local Hillel boards—dictate their own guidelines.