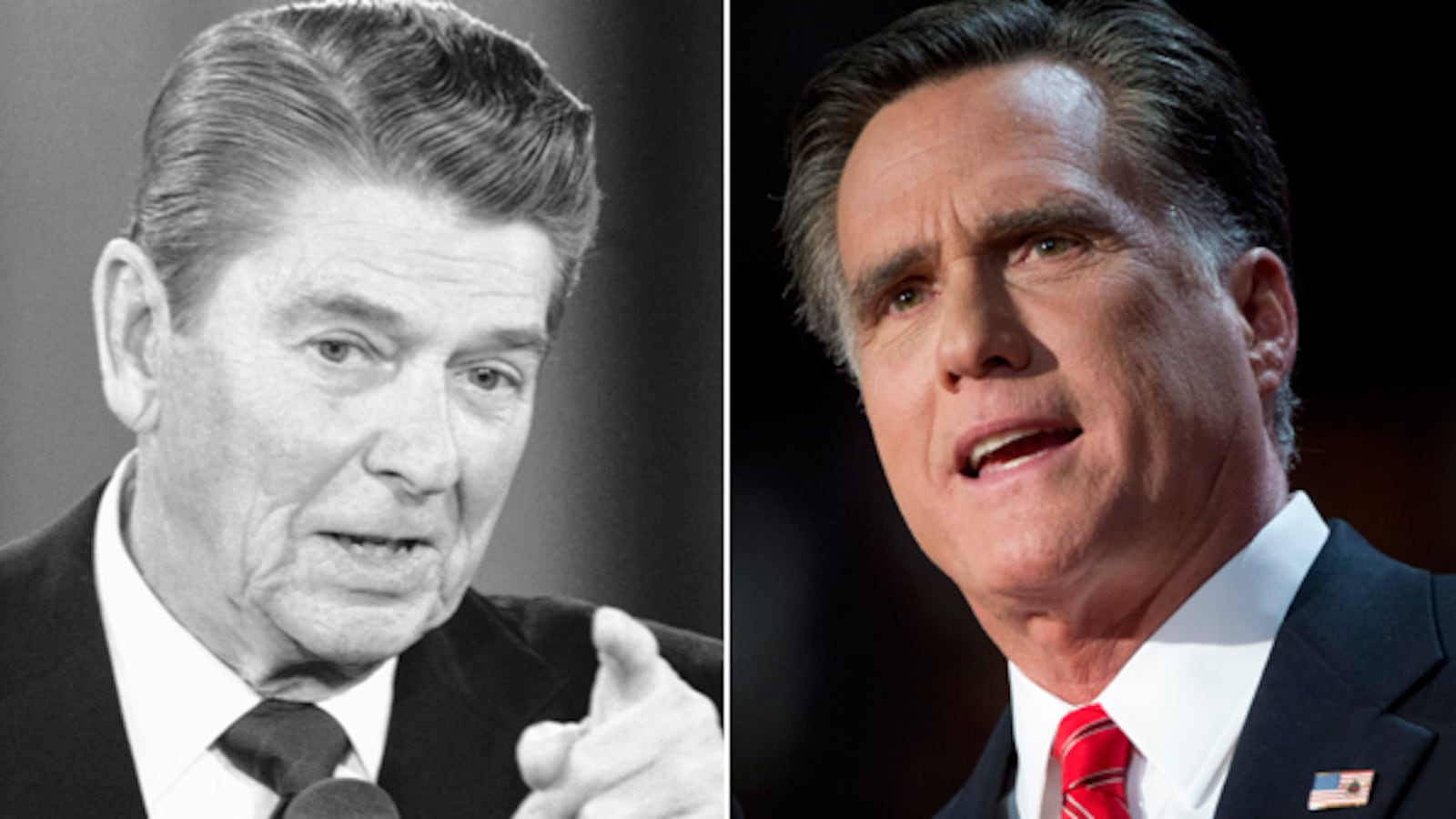

In a small but telling episode, Republican activists reportedly blocked a plan for a surprise speech outside the party’s convention—by a hologram of Ronald Reagan. They feared the projection would overshadow living candidate Mitt Romney’s speech accepting the GOP nomination.

It was the right call. The Tampa Republicans have resigned themselves to Romney, but they positively adore Reagan. The last thing they needed was a giant holographic image reminding them of how very unlike the Gipper their nominee is.

Reagan was the ultimate conviction politician. It helped, of course, that he was a genial ex-actor who knew how to deliver a line. But his political career was anchored in the bedrock of certain political beliefs: individual liberty, free enterprise, anti-statism, and America’s democratic mission. Even many who disagreed with Reagan or thought his views too simplistic admired his sincere and steadfast dedication to these principles.

Romney is the opposite. He is identified with no consistent body of political ideas or themes. He is pragmatic and transactional, doing whatever is needed to solve the problem at hand. That has served him well in business, but it has not equipped him for the ideological and inspirational demands of political leadership.

In accepting his party’s nomination last night, Romney, an uncommonly private politician, cracked open the door on his private life and feelings. He issued a stinging indictment of President Obama’s supposed failures, but had surprisingly little to say about what he would do differently. Romney offered the country his own glittering biography, not a governing agenda.

His stands on the issues, in fact, appear to be entirely situational. In liberal Massachusetts, Romney was pro-choice, concerned about global warming, tolerant on gay rights and committed to expanding health care. In the Tea Party–infused GOP nominating contest, he was pro-life, stridently anti-immigrant, unalterably opposed to tax hikes and an inveterate foe of “Obamacare,” despite its many similarities—including an individual mandate—to the universal coverage plan he supported in Massachusetts.

Romney probably doesn’t see himself as disingenuous or hypocritical; he simply adapted his positions and tactics to the exigencies of the party nominating battle. Don’t be surprised as he modifies them again over the fall campaign against President Obama. A man without an internal political compass, where he stands is strictly a matter of context.

That extreme elasticity made for some awkward moments in Tampa. As Ezra Klein observed, delegates lustily cheered Chris Christie and Paul Ryan when they argued that tough times demand honest and courageous leaders willing to tell voters what they need to hear, not what they want to hear. But Mitt Romney, who took the gold in flip-flopping during the primaries, is anything but a candidate of hard truths.

Addressing the party faithful in the hall and the millions of Americans watching him on television, he didn’t ask for any sacrifice. Like a motivational speaker, he asks only that Americans believe in themselves. Sounding like a cross between George Babbitt and Ward Cleaver, he affirmed the traditional gospel of success through faith and family, self-reliance and free enterprise, while offering no detail about the policies behind that pitch. He asks voters to believe in an American mythos that leaves out all the imperfections, tragedies, and moral conflicts that are as integral to our national story as the freedoms and opportunities he extolled.

In this sense, Romney is the anti-political candidate. He is uncomfortable talking about his political philosophy or public policies, or about going into the devilish details about his time in the private sector. At the convention, he offered his services on the basis of his private virtues as a husband, father and pillar of his church—topics that the uncommonly private politicians had previously tried to avoid engaging—as well as his competence in mastering complex challenges, like turning around a failing company or rescuing the Salt Lake City Olympics.

His argument isn’t about a better direction for America. What America needs now, he argues, is not a political visionary or polished speechifier like Barack Obama, but a certified turnaround artist like Mitt Romney.

Such, at any rate, is Romney’s case. It does not make the heart pound, or inspire the kind of devotion that leads people to stick with their leaders through thick or thin. Reagan was the captain of the conservative cause; Romney offers himself as the mechanic America needs to repair its misfiring economic engine.

Little wonder that Republicans in Tampa didn’t exactly fall in love with Mitt Romney, even if they accepted him as their standard bearer. Just don’t expect them to be naming airports and buildings after Romney, even if he wins.