The blame game has begun. The latest round of diplomacy on Iran’s disputed nuclear program is on life-support and may fully collapse during next week’s technical meeting in Istanbul. Few expect anything grand to come out of that meeting—including the parties themselves. That’s why they are preparing themselves for the inevitable blame game instead.

Obviously, the vast majority of the blame will be spared for “the other side.” Immediately after the last meeting in Moscow, Iranian officials complained about “Western dishonesty.” Even former President Hashemi Rafsanjani, who is considered more moderate on the nuclear issue, had harsh words for the P5+1. “The talks showed that Western sides are not interested in interaction, are not honest, and have based their policy only on bullying in order to find an opportunity to achieve their objectives in the future,” he said.

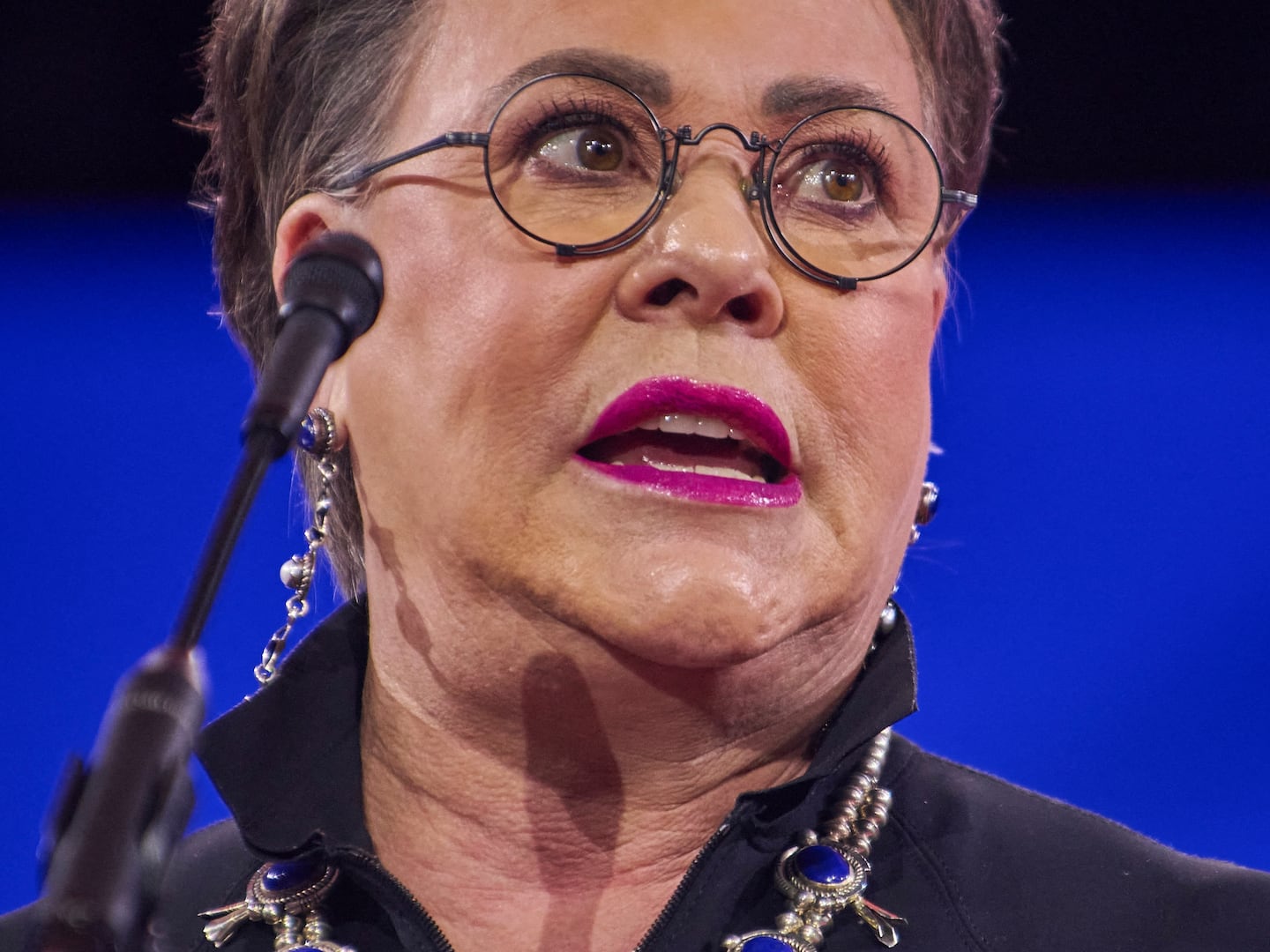

And European foreign policy chief Catherine Ashton put the onus on the Iranians, arguing that Iran had yet to decide whether it wanted diplomacy to work.

But now finger-pointing within the P5+1 is also beginning to emerge.

Al-Monitor correspondent Laura Rozen reports that some P5+1 members have concluded that the “United States hardened its position in Moscow” and walked back from offers it had made in Istanbul and Baghdad. Russian lead negotiator and Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov complained to former AFP reporter Michael Adler that the US and the EU should accept Iran’s right to enrich uranium. "What in the world precludes the US, France, and others to recognize this very simple fact?" he asked.

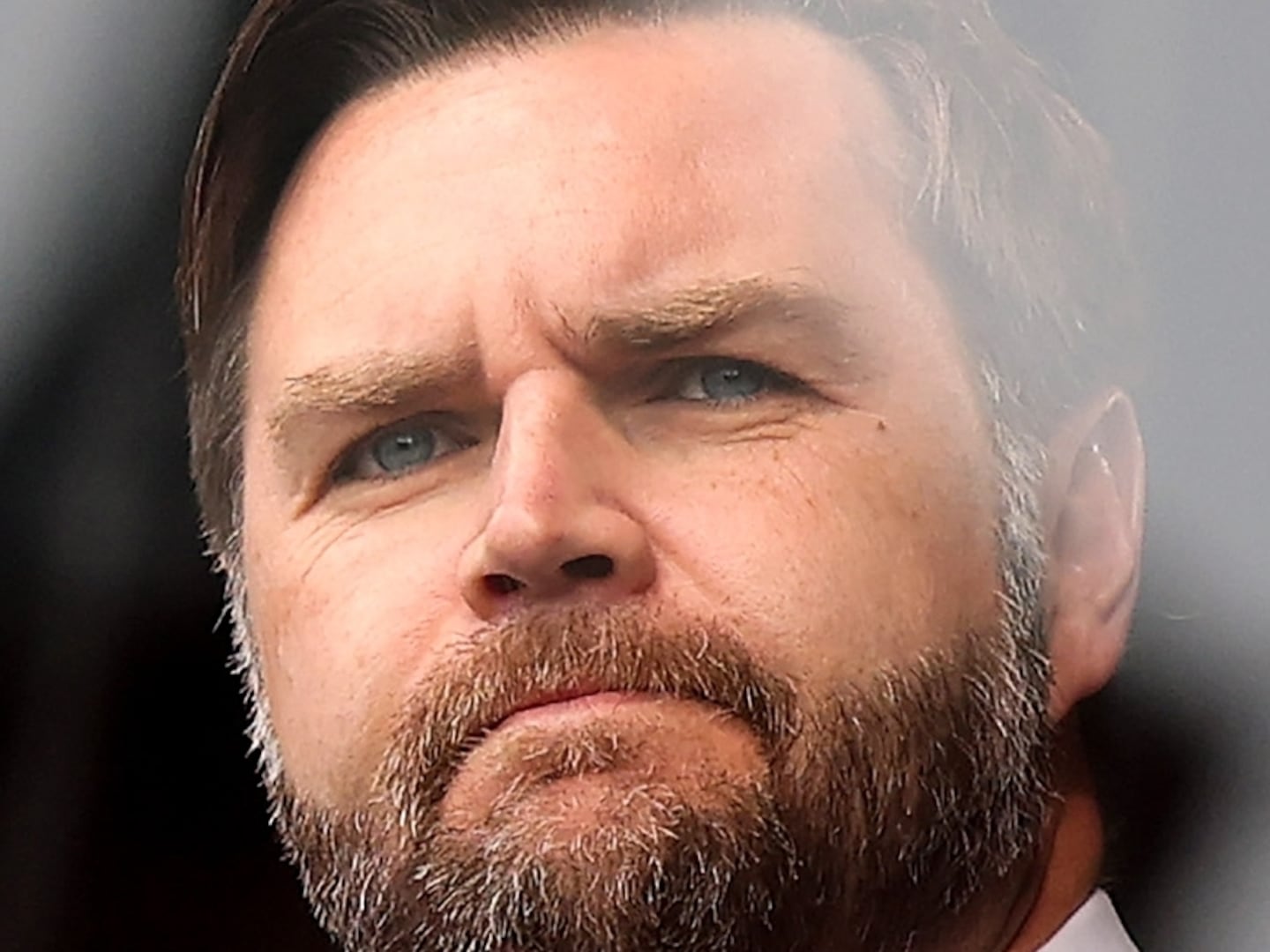

The frustration seems to lie in the fact that the imperative of keeping a united front vis-à-vis Iran meant that the P5+1 had to adopt a negotiation position based on their lowest common denominator. That is, the rest of the P5 had to adjust to what was politically acceptable to the Obama administration. And with elections around the corner, Obama’s political margins are narrow.

In fact, the reason a deal could not be reached in Moscow seems largely be rooted in US political calculations. Pressure on the Obama administration from members of Congress—both Republicans and Democrats—and from Israel grew considerably after the successful meeting in Istanbul in April.

Demands were made that Obama should not offer Iran any sanctions relief in return for Iranian nuclear concessions. A House resolution was passed with overwhelming majority using Bibi Netanyahu’s red line on the nuclear issue (no enrichment) instead of Obama’s (no nuclear weapon).

To the White House, this meant that if a small interim deal was struck, the domestic political cost would be considerable. Both Obama’s Republican opponents, as well as his fellow Democrats in Congress, would chastise him for having offered Iran too much if the sanctions were touched or if Obama honored his earlier signal that limited enrichment on Iranian soil under strict inspections could be accepted by the US at the end of the negotiations.

And as former Presidential adviser Aaron David Miller said during a NIAC conference immediately after the Baghdad talks, Obama is very vulnerable to criticism from Israel: “Keeping [the Israelis] away from adding to the President’s political problem between now and November is going to be extremely important,” Miller said. “The Israelis cannot start making noise in Washington about their unhappiness about how these talks are going.”

Ultimately, the political reality in Washington meant that in Moscow, success would be failure, and failure would be success. Since the political cost of a small deal was deemed higher than the political cost of no deal, failing in Moscow would translate to success in Washington. So according to diplomats from the P5+1, Obama changed the goal post and sidestepped the principle of reciprocity and made demands of the Iranians without offering anything in terms of sanctions that Tehran viewed as valuable. That way, the President could assert that he offered no compromise and no sanctions relief – which would cause failure in Moscow but be well received in Washington.

In political terms, the Obama Administration’s strategy seems to have worked. The talks failed to produce an agreement—and no one in Washington complained. There were no sustained attacks from the Republicans. No complaints from Netanyahu. Democrats in Congress stayed silent. In fact, Obama was praised for having stood firm—and refusing to reach a compromise.

But what is politically expedient in the short term may be detrimental in the medium-term and disastrous geopolitically. Come November, the failure to reach a deal may become a political liability. The Republicans will still criticize Obama’s record on Iran, accusing him of having failed to stop Iran’s nuclear program, betraying the Iranian people and not standing up for Israel’s security. They have no choice but to attack Obama, and Iran is viewed by the Republicans and by Israel as Obama’s weak spot—deal or no deal.

In the absence of a deal, even a small interim deal, Obama’s defense line will solely be that he has been tougher on Iran than the Republicans because of the international support for sanctions he has managed to manufacture. Once again, a Democratic President will compete with the Republicans on who can be tougher, not who can be smarter.

This will be an argument that will do little to energize Obama’s own base and activate the very energy needed to change the political reality in Washington in order to make a breakthrough in the negotiations both a nuclear and political success.

Despite the short-term cost, even an interim deal would have benefitted Obama better by November.