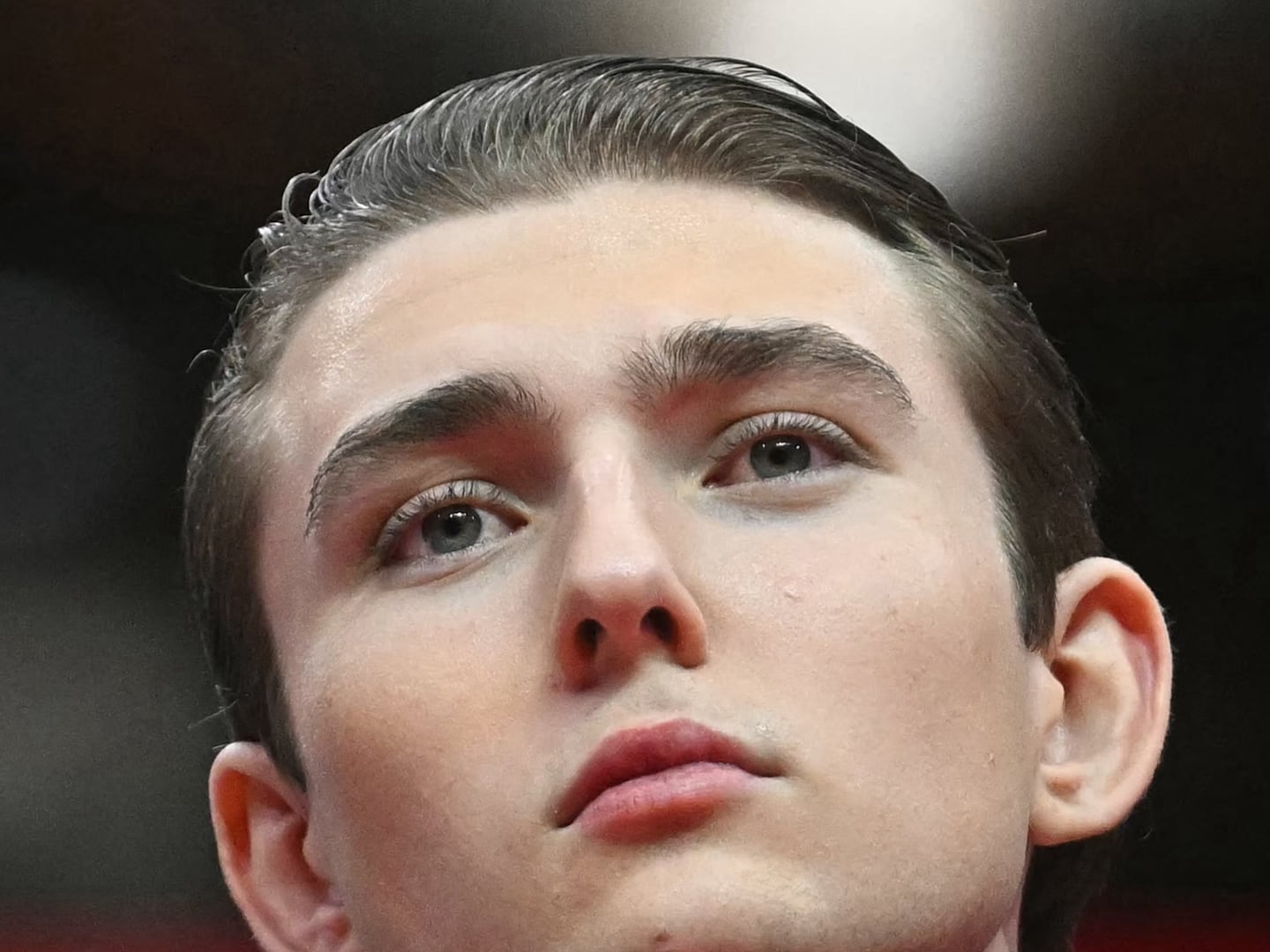

Near the end of the second act of The Member of the Wedding, a play adapted from the Carson McCullers 1946 novel of the same name and running all week at this summer’s Williamstown Theatre Festival, a 12-year-old white girl named Frankie (Tavi Gevinson) climbs onto the lap of her caretaker, a middle-aged black woman named Berenice Sadie Brown (Roslyn Ruff).

“Have you ever thought about this? Here we are—right now. This very minute. Now.” Frankie says. “But while we’re talking right now, this minute is passing. And it will never come again. Never in all the world. When it is gone, it is gone. No power on earth could bring it back again.”

Frankie, an androgynous misfit on the cusps of teendom, is filled with observations like these: trite, but cutting—the kind of theatrical philosophizing usually reserved for stoners, cult members or anyone else unburdened by fear of cliche.

Most of Frankie’s insights ring oddly true, but this particular consideration lands with a good deal of irony—partly because Frankie is speaking in a play, but mostly because the production itself, which is set in 1945—the year before the novel was written—could have easily been talking about today.

The story, which unfolds over the course of a weekend with a brief epilogue three months later, follows Frankie and Berenice as they learn that Frankie’s older brother Jarvis will be married to his sweetheart, Janice.

Frankie, obsessed by the notion of “membership” and belonging, falls in love with the wedding, and concocts an imaginative plot to accompany the couple on their honeymoon.

Berenice, another outsider with a blue glass eye, a no-nonsense sensibility, and four failed marriages of her own (each an attempt to recreate the ferocious, “shivering” love of her first husband) plays Frankie’s anchor – and arguably the anchor of the whole show – endeavoring to bring her outlandish expectations back to earth.

Throughout the three act play, director Gaye Taylor Upchurch stages McCullers’ portraits of boiling racial tensions, the common desire for community, and the confusing strictures of gender identity—depictions so familiar that it is alternately hard to believe how old they are and disturbing to register how recent they could be.

“It’s the perfect play to revive right now, because Carson McCullers was writing in such a progressive way about race, about gender,” Upchurch told The Daily Beast. “It’s a hard look at race relations in America at that time. It’s set in 1945—but at this moment, with Black Lives Matter, and how we’re starting to investigate what America is really like, particularly for black people living in it, it harkens back to that time. Unfortunately, it’s not too difficult to draw a thread between what’s going on in 1945 to some of the white supremacist rhetoric that’s going on in 2018.”

In the first act of The Member of the Wedding, for example, a young black horn player named Honey Camden Brown (played by Will Cobbs) storms into Frankie’s warmly lit kitchen, holding his head in his hands. As he uncovers his forehead, Berenice, Honey’s foster sister, examines a massive wound at his hairline. “Why, it’s a welt the size of a small egg,” she says. “What were you doing?”

“I was just passing along the street minding my own business when this drunk soldier came out of the Blue Moon Café and ran into me. I looked at him and he gave me a push. I pushed him back and he raised a ruckus. This white M.P. came up and slammed me with his stick.” Berenice’s boyfriend, an elegant bald man who goes by T.T., quietly observes: “It’s the kind of accident that could happen to any colored person.”

Later, after spitting at a white soldier, fleeing the state with just six dollars to his name, and getting arrested by the authorities, Honey hangs himself in his cell.

Upchurch, who grew up in Jackson, Mississippi, said McCullers’ gothic language, and portrayal of white cruelty in the mid-century Southern city rang true to her. The director’s family had their own complicated racial legacy.

Throughout the 1900’s, her grandparents owned The Clarion-Ledger, a once profoundly racist publication serving the greater Jackson area which, like most of the white-run papers, publishers, and writers of the time, largely ignored the racial violence Honey describes and lives in the play.

Only in the late 1970s, when they started to overhaul the newsroom, hiring black journalists and journalists from the North— according to this Global Journalist report—did the Ledger begin to report on the city’s African-American community.

As acute American racism crackles around Frankie and Berenice, she and her cousin, a round, pre-pubescent boy named John Henry, explore another kind of quiet tension: the stiff categories of gender which don’t allow them the “fluidity” they would like.

In the novel, during a game Frankie, John Henry and Berenice play, where each can envision their ideal world, Frankie wishes “that people could instantly change back and forth from boys to girls, whichever way they felt like and wanted.”

That same desire—though not repeated verbatim in the script – plays out onstage. Frankie, who keeps her hair shaved in a close crew cut, has trouble relating to the girls of the town and often imagines she will “dress up like a boy and join the Merchant Marines.”

Her outfits range from a boyish combination of shorts and T-shirt to an elaborate orange evening gown, so theatrical and flamboyant it almost reads as drag. (When Frankie’s father first sees the dress, he says he thought it was a “show costume.”)

John Henry, who modifies his cousin’s imaginary world to make everyone “half boy and half girl” in the novel, performs a similar kind of gender fluidity, embracing feminine signifiers in a way it’s hard to imagine in the 1940’s American South. (Upchurch believes the character was based in part on McCullers’ childhood friend and sartorial icon Truman Capote, although there are no primary source documents to verify the claim).

In the penultimate scene, for example, John Henry tears across the stage in a gargantuan tulle fairy costume.

On questions of gender and sexuality, McCullers was decades ahead of her time. Though married to a man and not openly gay or bisexual, McCullers often fell in love with women, perhaps platonically or romantically. “There’s a story of her being at [the writers’ colony] Yaddow at the same time as Katherine Anne Porter, and she becomes obsessed with her,” Upchurch told The Daily Beast.

“She kept knocking on her door, and finally Katherine Anne Porter says, ‘I’m not coming out until you go away.’ After a few hours she hadn’t heard anything from Carson. So, she opened her door and Carson was lying across the threshold of the door. Things like that, these obsessions—wonderfully bizarre, yet almost scary.”

On another occasion, in April of 1963, when McCullers visited Charleston, South Carolina, she met a young Gordon Langley Hall at a party.

Years later, Hall would become one of the first people to undergo gender affirmation surgery and re-emerge into public life as Dawn Pepita Hall. But at the party in Charleston, Hall still looked and walked through society life very much as a man. In an interview from 1971, Hall recalled that McCullers had studied her, quietly taking in her masculine body, and then noted: “You’re really a little girl.”

McCullers’ ability to see things as they were animates The Member of the Wedding and—three quarters of a century later—gives the play an unnerving familiarity.

Throughout the production and the novel, Frankie remarks to Berenice, with the vague matter-of-factness of pre-teen philosophy, that the world is a “sudden place.”

She meant that things speed up, Upchurch said, that they can change quickly: “It just takes one little thing to happen to make everything feel like, ‘Wow, that came out of nowhere and that was so fast.’” But watching the production in 2018, seventy three years after the story first hit the market, the world doesn’t seem very sudden at all.

“Well, I don’t know,” Berenice demurs. “Sometimes sudden and sometimes slow.”

The Member of The Wedding is at Williamstown Theatre Festival until August 19. Book here.