A cleansing bout of craziness in 2012 could be just what the GOP needs.

I’m talking about a nominee so far to the right that conservative populists get their fondest wish—and the Republican Party is forced to learn from the result. Namely, that there is such a thing as too extreme.

The dangerous groupthink delusion being pushed in conservative circles over the last few years is that ideological purity and electability are one and the same. It is an idea more rooted in faith than reason.

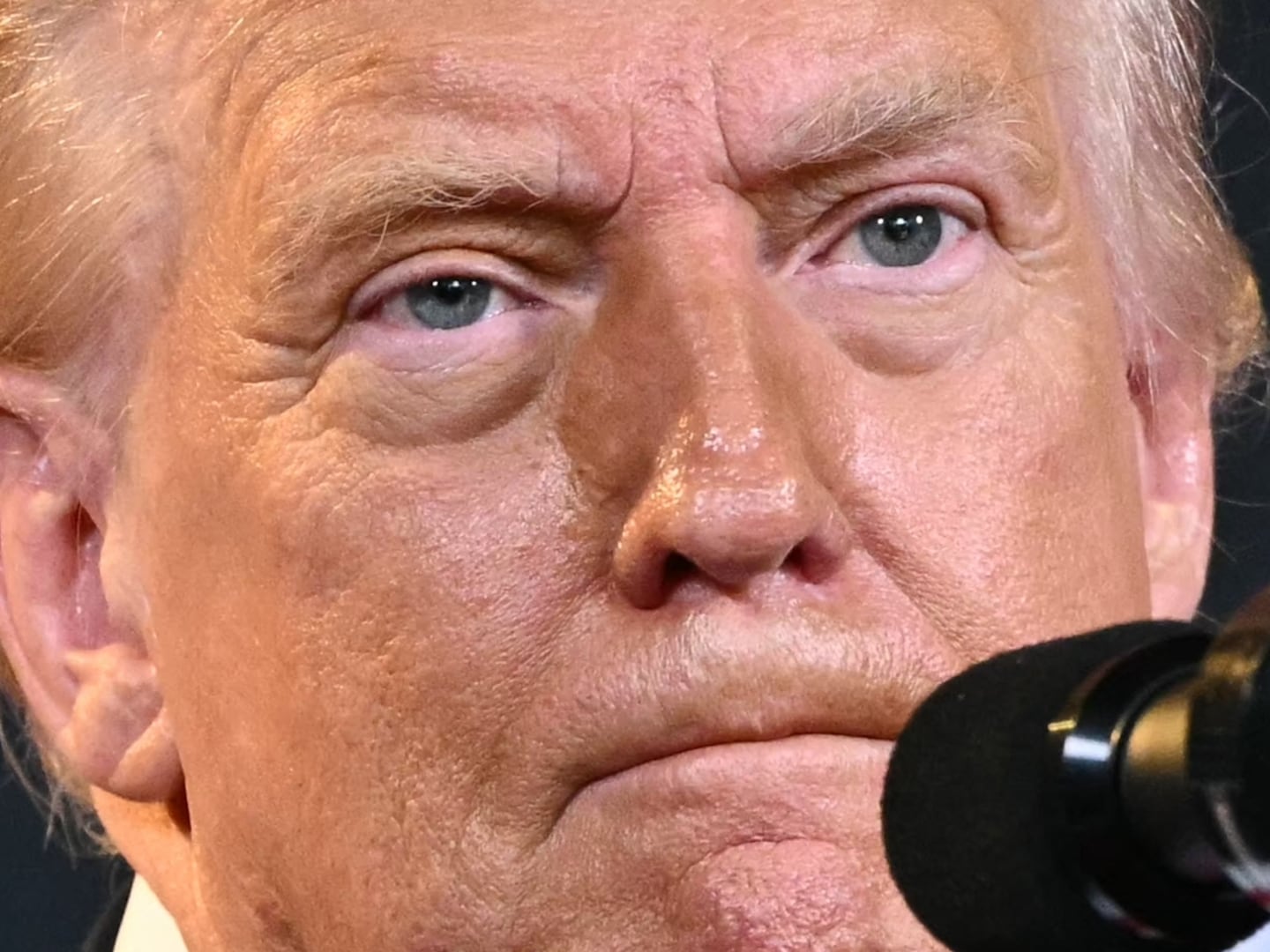

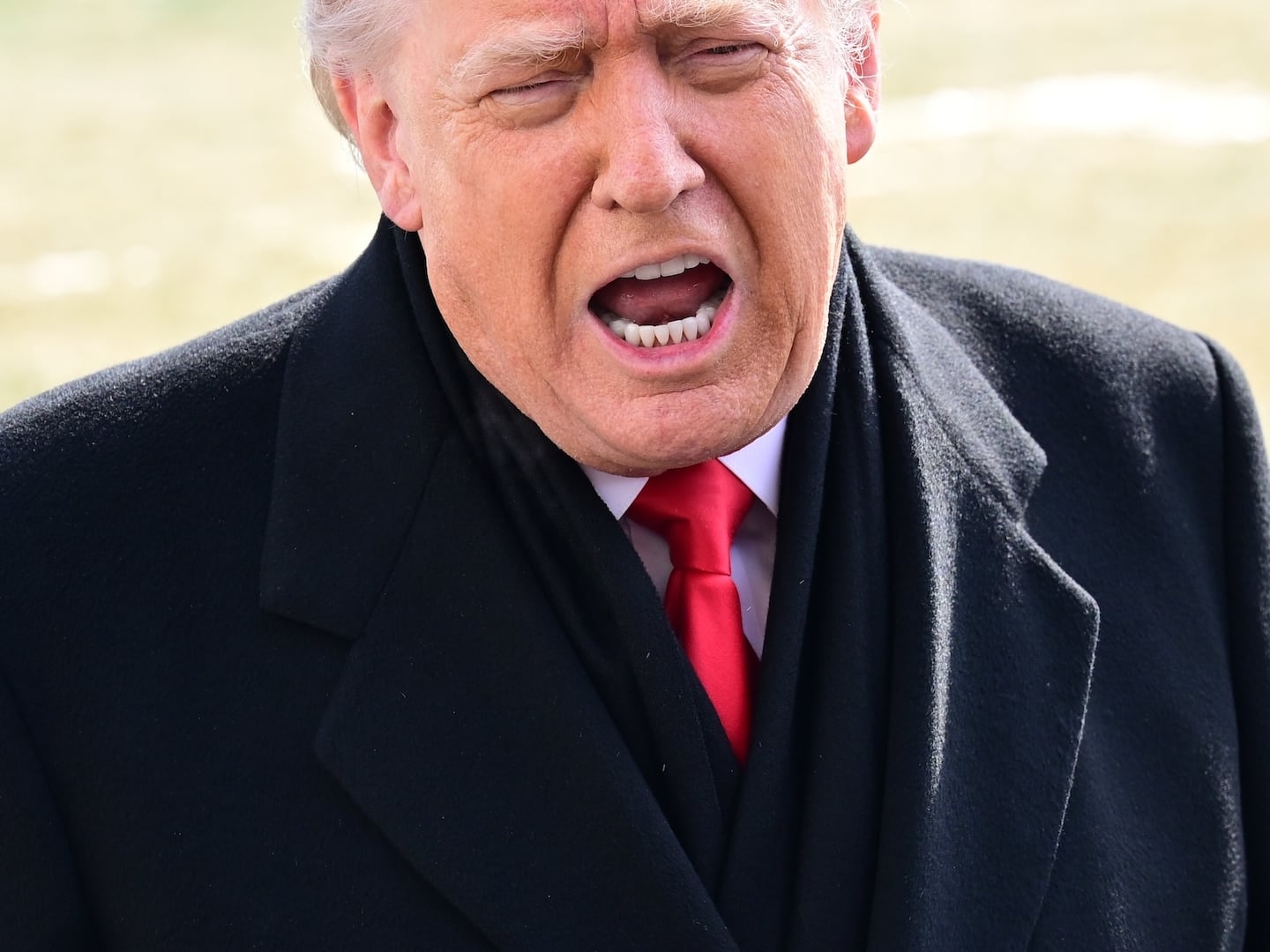

If Mitt Romney does finally wrestle the nomination to the ground, and then loses to Obama, conservatives will blame the loss on his alleged moderation. The right wing take-away will be to try to nominate a true ideologue in 2016.

But if someone like Rick Santorum gets the nomination in an upset, the party faithful will get to experience the adrenaline rush of going off a cliff together, like Thelma and Louise—elation followed by an electoral thud.

This could be educational. After all, sometimes you have to hit rock bottom before you recognize your problems.

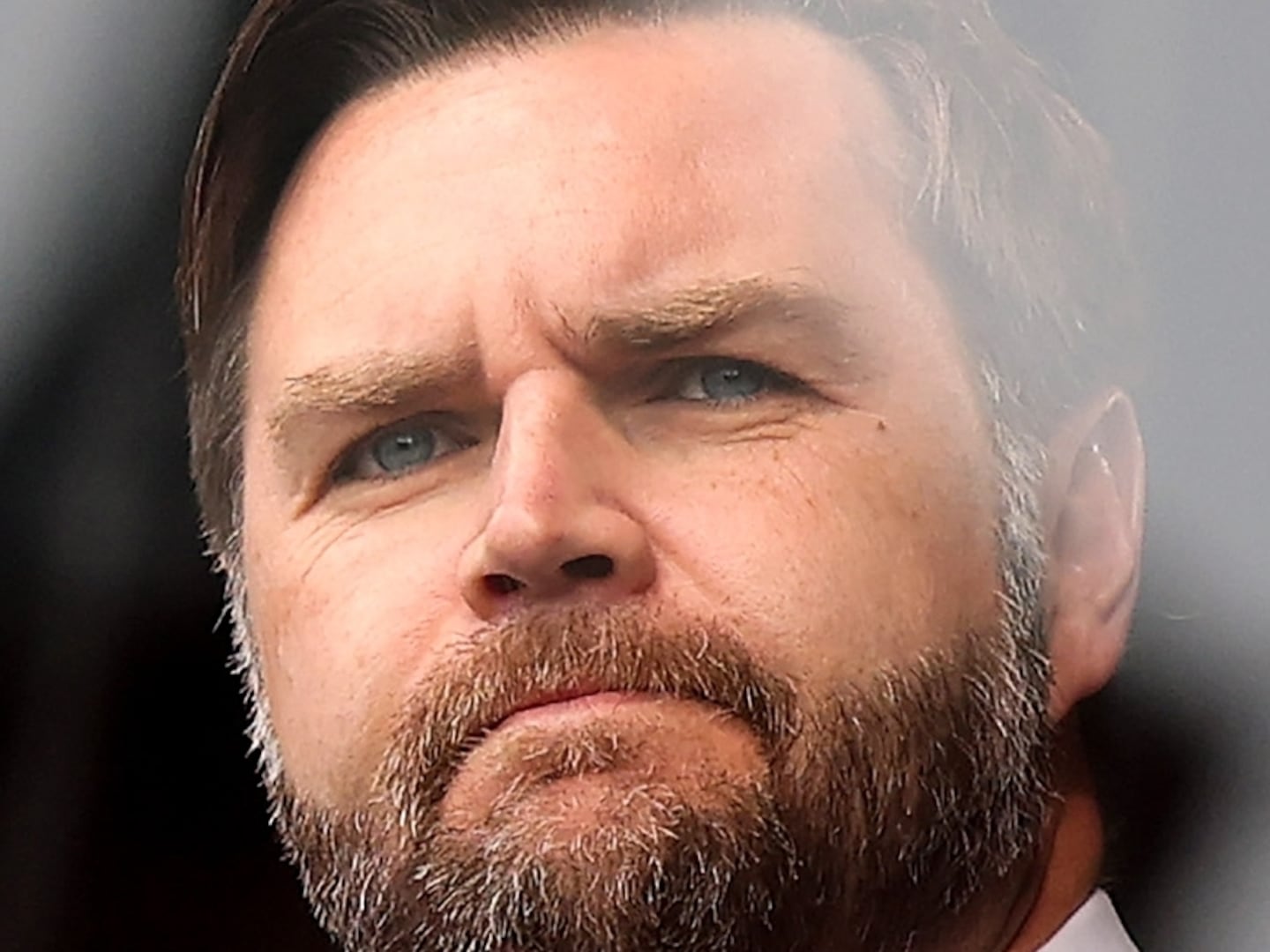

Giving a self-identified “full-spectrum conservative” theo-con like Santorum the nomination would mean we’d really have a “choice, not an echo” election in November. Republicans would be forced to confront the fact that talk about Satan attacking America, negative obsessions with homosexuality, contraception and opposition to abortion even in cases of rape and incest alienates far more people than they attract.

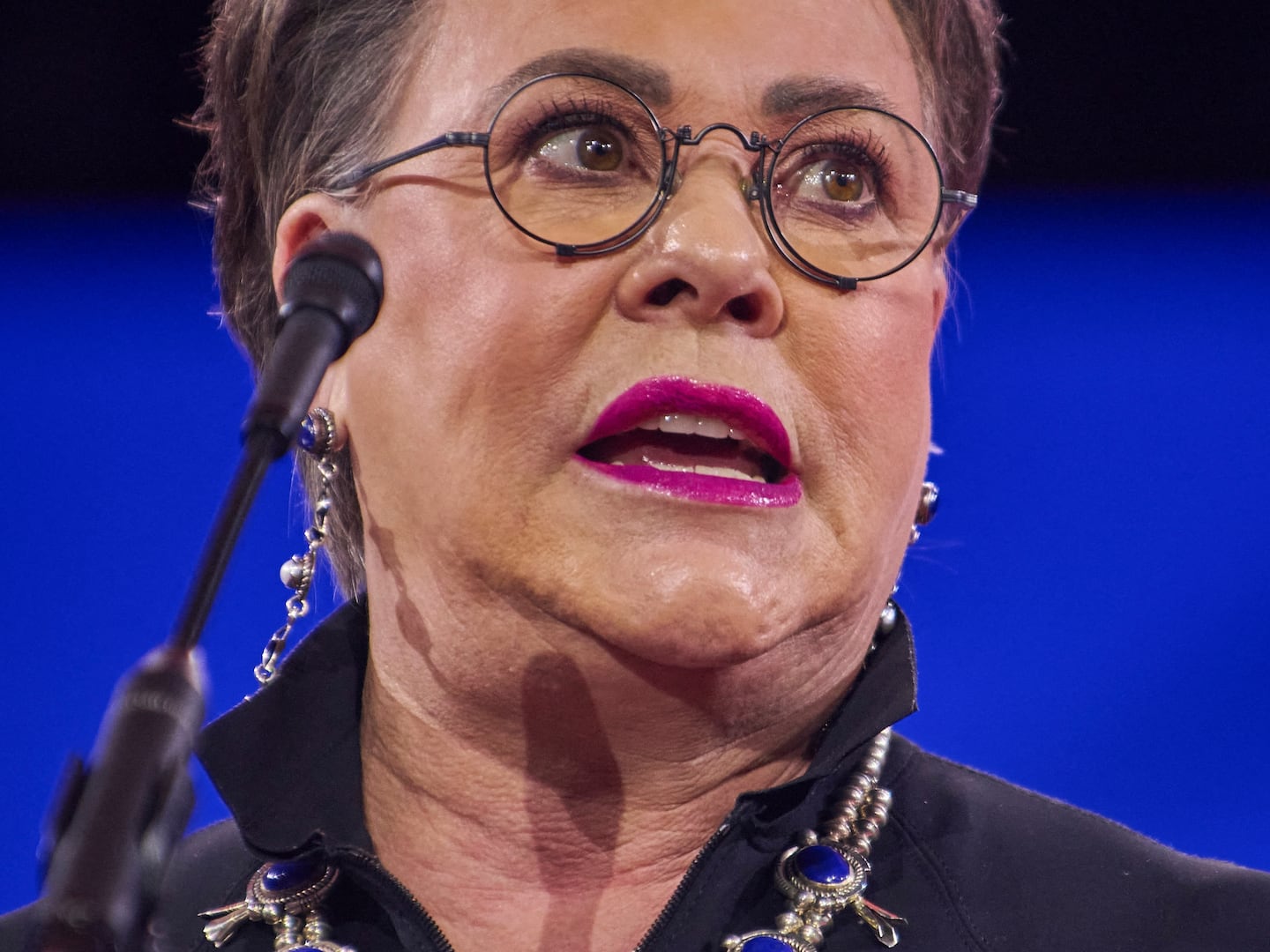

Our politics are looking more and more like a cult because of unprecedented polarization—any issue where there is deviation from accepted orthodoxy leads to an attempted purge. It is absurd that clownish conservative caricatures like Michele Bachmann and Herman Cain were briefly elevated to the top of the polls while more sober-minded presidential candidates with executive experience like Tim Pawlenty and Jon Huntsman Jr. failed to gain any traction. The result is the weakest Republican field in living memory.

That the conservative favorite from 2008 is now derided as a RINO says more about the rightward lurch of the Republican Party than it does about Romney. You reap what you sow.

The Tea Party driven win of 2010 seems to have taught some in the GOP that firing up the base with extreme anti-Obama rhetoric leads to victories, and so candidates like Gingrich happily comply with talk about “Kenyan anti-colonial” mindsets and “secular socialist machines.” The obvious fact that this works better in comparatively low-turnout, high-intensity midterm elections than in the broader, more representative turnout of presidential years has been ignored, willfully or otherwise.

Likewise, it’s been scrubbed from many conservative’s memories that the Tea Party in 2010 used libertarian appeals to attract independents—avoiding more polarizing social issues and instead keeping a tight focus on fiscal ones like reducing the deficit and debt.

But in the wake of 2010, we’ve seen the social-conservative agenda reemerge with a vengeance, because Republican legislators in statehouses and Congress made it a priority. Not surprisingly, this has alienated independents, women, and young voters outside the conservative tribe.

But in a tribal time, ideological apparatchiks have outsize influence. They come to debates armed with their own facts. In their Kool-Aid-laden retelling of recent political history, unsuccessful GOP nominees like John McCain lost because of his independent center-right profile (rather than a backlash against the excesses of the Bush administration or the nomination of Sarah Palin). Barry Goldwater’s 44-state loss to Lyndon Johnson in 1964 is recast as a triumph because it allegedly led to Reagan’s landslide ... 16 years later. Nixon’s 49-state win in 1972 is stripped from the history books as winning candidates with shades of gray in their resume—Ike’s successful center-right two terms, George H.W. Bush’s country-club conservatism, or even W’s 2000 call for “compassionate conservatism”—are ignored as ideologically inconvenient.

Goldwater would be attacked as a RINO today for his rejection of the religious right, his wife’s cofounding of Planned Parenthood in Arizona, or his early support of gays serving in the military. Some conservative activists turned on Reagan during his White House years (the editor of the Conservative Digest memorably wrote in the early '80s, “Sometimes I wonder how much of a Reaganite Reagan really is”). Almost by definition, absolutists oversimplify, turning everything into a fight between angels and devils.

Giving conservative activists everything they want in a presidential nominee would ultimately be clarifying for the Republican Party. It would break the fever that has afflicted American politics turning fellow citizens against one another. It would restore a sense of balance, recognizing that it is unwise to systemically ignore the 40 percent of American voters who identify themselves as independent or the 35 percent who are centrist. After all, a successful political party requires both wings to fly.

There’s nothing like losing 40 states to refocus the mind.