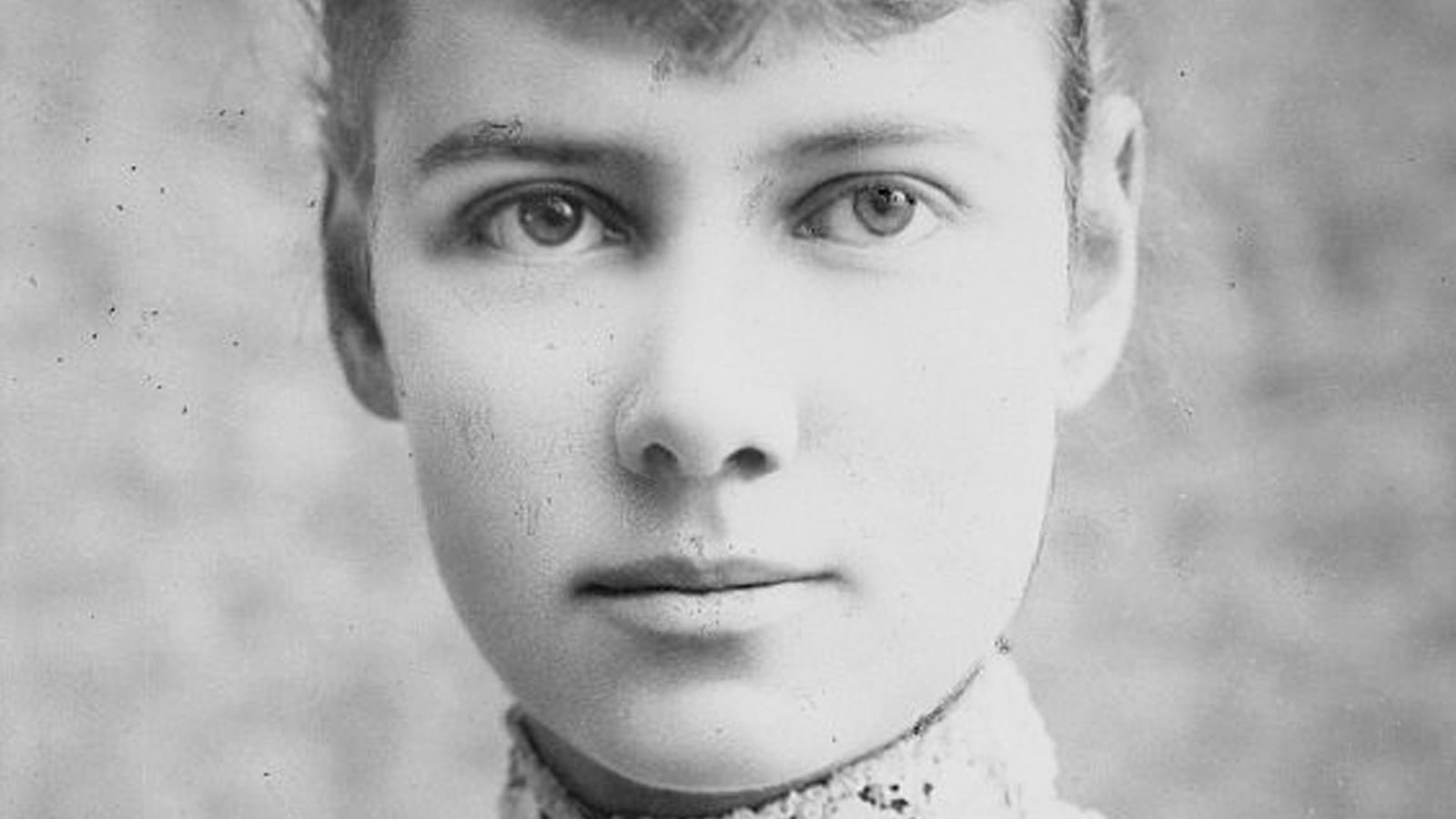

Long before Jessica Mitford would publish The American Way of Death, her explosive exposé on the corrupt American funeral system in 1963, there was a young muckraker who called herself Nellie Bly. Born Elizabeth Jane Cochran in 1864, Bly responded anonymously (but with much verve) to an article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch in 1885 that mocked women looking for work. The editor was so impressed with the response that he advertised for the responder’s identity, hoping to hire her. Hire her he did, and when she became frustrated by only receiving assignments related to the domestic sphere, she became a freelancer, chose the pseudonym Nellie Bly, and went on to write some of the most provocative journalism of her time.

Now, to complement the biography of Bly published in 1995 by Brooke Kroeger, Jean Marie Lutes, a professor of English at Villanova, has compiled a great deal of Bly’s writings into the splendid Around the World in Seventy-Two Days and Other Writings. If you assume the word “provocative” cannot mean the same thing in the late 1800s as it does today, you will be in error. For the very issues Bly made her focus, such as women’s pay, the treatment of the insane and infirm, and immigration, just to name a few, are still very much relevant concerns of 2014.

In her response to that despicable article suggesting that women should only concern themselves with being creatures of leisure, Bly pointed out that not all women are blessed with the choice to work or stay at home. “When duties are over for the day, with tired limbs and aching head, she hastens sadly to a cheerless home. How eagerly she looks forward to pay day, for that little mite means so much at home. Thus day after day, week after week, sick or well, she labors on that she may live ... This poor girl does not win fame by running off with a coachman; she does not hug and kiss a pug dog nor judge people by their clothes and grammar; and some of them are ladies, perfect ladies, more so than many who have had every advantage.”

She even goes on to quote an average salary of a male office worker ($2 a day) versus the going rate “just as girl”—a paltry $5 a week.

But the piece that was to make Bly’s name was her exposé of the insane asylum on New York's Blackwell's Island. Pretending to be Cuban, Bly was committed there and found that most women in the asylum were in fact not insane but immigrants who could not communicate with their jailers or single women without a place in society. Bly stayed there for 10 days and described the horrible treatment and conditions of the place. “Suddenly I got, one after the other, three buckets of water over my head—ice cold water, too—into my eyes, my ears, my nose and my mouth. I think I experienced some of the sensations of a drowning person as they dragged me, gasping, shivering and quaking, from the tub. For once did I look insane, as they put me, dripping wet, into a short canton flannel slip, labeled across the extreme end in large black letters, ‘Lunatic Asylum, B.I.H. 6.’”

The publication of the piece in the New York World in 1887 earned Bly a full-time position—and, by the end of the year, as Lutes remarks in her notes, the city had increased the budget for the Department of Public Charities and Corrections “with $50,000 earmarked for Blackwell’s Island asylum.”

Bly would go on to champion the rights of laborers and women, interviewing and publishing pieces on “box girls,” women who labored in a box factory, and on Belva Lockwood, the first female lawyer to argue before the Supreme Court and the first woman ever to run for president of the United States in 1884, and none other than Susan B. Anthony, who Bly called the “champion of her sex.” She would even author an article published in 1888 that asked the question “Should women propose?” Marriage, that is.

In another life-changing assignment, Bly was sent on a trip around the globe in 1890. The journey and its subsequent piece (which was then collected into a book) made her a household name—readers could even keep up with Bly’s exploits on a board game or make their guess about how long the journey would take. Afterwards, Bly made the somewhat strange decision of supporting Austria during World War I—she had traveled there to be on the front lines and sent back many a dispatch about the difficulties of war on both sides—but her stance made her relationship with her home country a bit tricky.

By then she had married, according to Maureen Corrigan’s foreword, “a millionaire industrialist nearly forty years her senior.” But never one to rest on her laurels, Bly took over control of the company, “marketed the first steel barrels in America and filed several patent applications for inventions, including a stacking garbage can.” But the world to which Bly had returned was a very different one. She continued to write, mostly through an advice column “Dear Nellie,” at The New York Evening Journal. Legal issues with her deceased husband’s children and her lessening salary led to difficulties and Bly eventually died, of pneumonia, at St. Mark’s Hospital.

An Internet search today of her name came up alongside the label “yellow journalism,” which is defined as “journalism based upon sensationalism and crude exaggeration.” The work of Nellie Bly may have been sensational, but it was by no means exaggerated or crude—as we know now, the conditions she exposed both in the labor industry and in the asylum were cruel, and barely short of torture.

The only thing unbelievable about Nellie Bly is that it’s taken this long for her work to be recognized—and with a life story this rich, where is the biopic? Thanks to this new collection at least, Bly’s life work will be accessible for a whole new world of readers.