Our love of art often leads us to seek out more information about the artists themselves. We guiltily (or not so guiltily) read US and People; we crave information about the creators of the movies, books, and music that have meant so much to us. Who are they, these people who have the power to stir our most private emotions, to provide comfort to us when we're feeling lonely or depressed? This curiosity with glimpsing behind the scenes all started for me when I was 8 years old and my parents took me to see Charles M. Schulz, the creator of the Peanuts comics.

My love of Peanuts started a few years before that, when I was 5. On Sunday mornings my parents slept in. I would creep out the front door in my pajamas and bare feet to get the Sunday paper, and rifle through it to find that beautifully psychedelic explosion of color—the funny pages. I read them all, even the serials that I didn't understand, like Mary Worth and Rex Morgan, M.D. (Did Mary Worth have a job? A home?) But Peanuts was my favorite. The stories were told from the point of view of kids. The drawings showed the view down low to the ground, where I was—not like the view when I was up on Dad's shoulders. They were drawn simply and because of that, were inviting to a young child, not complicated like Dick Tracy where you had to study the panel to figure out what was going on. For my 6th birthday, my parents surprised me with two Peanuts books, collections of weekly published comics. I was amazed—I had no idea that one could take the newspaper comics and put them all together so that I could read them whenever I wanted. It was a revelation for me.

And so began a lifelong fascination with books, with humor, and with comics. I was a solitary kid, preferring to spend my time with Charlie Brown, Linus, Snoopy, and also The Hardy Boys, Tom & Huck, and Henry Huggins (whose nemesis, Ramona-the-pest, reminded me a bit of Lucy). During the summer when I was eight, my parents took me and my four-year old sister on a long, long drive (more than two hours!) up north to visit the couple who had run the summer camp my father went to as a child. He loved "Mom" and "Pop" Walton as much as he loved his parents. I read my Peanuts books in the car, and read some of the strips to my little sister. We all had lunch at the Walton's farm in Forestville, surrounded by apple trees and trails, ant hills and creekside salamanders – all wonderful things to an eight-year old. On the way home, I saw a road sign that read "Sebastopol." I couldn't contain my excitement, and started bouncing up and down on the back seat of the car.

"Mom! Dad! Look!!! It's Sebastopol!"

"Yes, dear, that's the next town. Why is that exciting?"

"Sebastopol – that's where Charles Schulz lives!" I quoted a line from the about the author paragraph in my Peanuts books, “’Charles Schulz lives with his wife and beagle in Sebastopol, a small town in Sonoma County, California.’ Can we go see him? Can we please?”

My sister chimed in, "Please Daddy?" She has always had my back.

They pulled over at a Flying A gas station and my Dad gamely looked up the number in the phone book, called, and then came back to the car. With a somewhat puzzled look, my father said "He says he'd be happy for us to come over."

We drove for 10 minutes past flat one-story houses, each with a short, crisp lawn that looked like a small golf course.

Dad stopped the car in front of one and said we were here, but it didn't look anything like I imagined. It was a wooden house with a low roof, a very wide house as though all the rooms were just laid side-by-side in a straight line. The front wall of the entrance didn't reach all the way up to the roof, there was a big cut-out space that you could see through to fruit trees in the back. It looked a bit like the architect Wilbur Post's house on the TV show Mister Ed. It looked so…normal. I don't think I was expecting a gingerbread house but I expected something a little more fun. Mom and Pop Walton's house was an old farmhouse with weeds everywhere, hidden cupboards, and siding you could lift off to find ants, and a cellar with an outside entrance, and crickets crawling up the porch. That was a fun house. This place looked too clean to be any fun.

We rang the bell and a man opened the door. Grey socks. Grey trousers. Short bristley hair. No smile. Old. This was Charles Schulz.

Inviting us in, he offered us lemonade that his wife had in a big pitcher. It was sour and they made me and my sister drink out of paper cups while the adults drank out of glasses. They wouldn't let us take our drinks out of the entry because there were carpets in the other rooms. All this time his beagle lay motionless on the floor in the entry hall. He was not dancing Snoopy's Christmas dance, or even walking around.

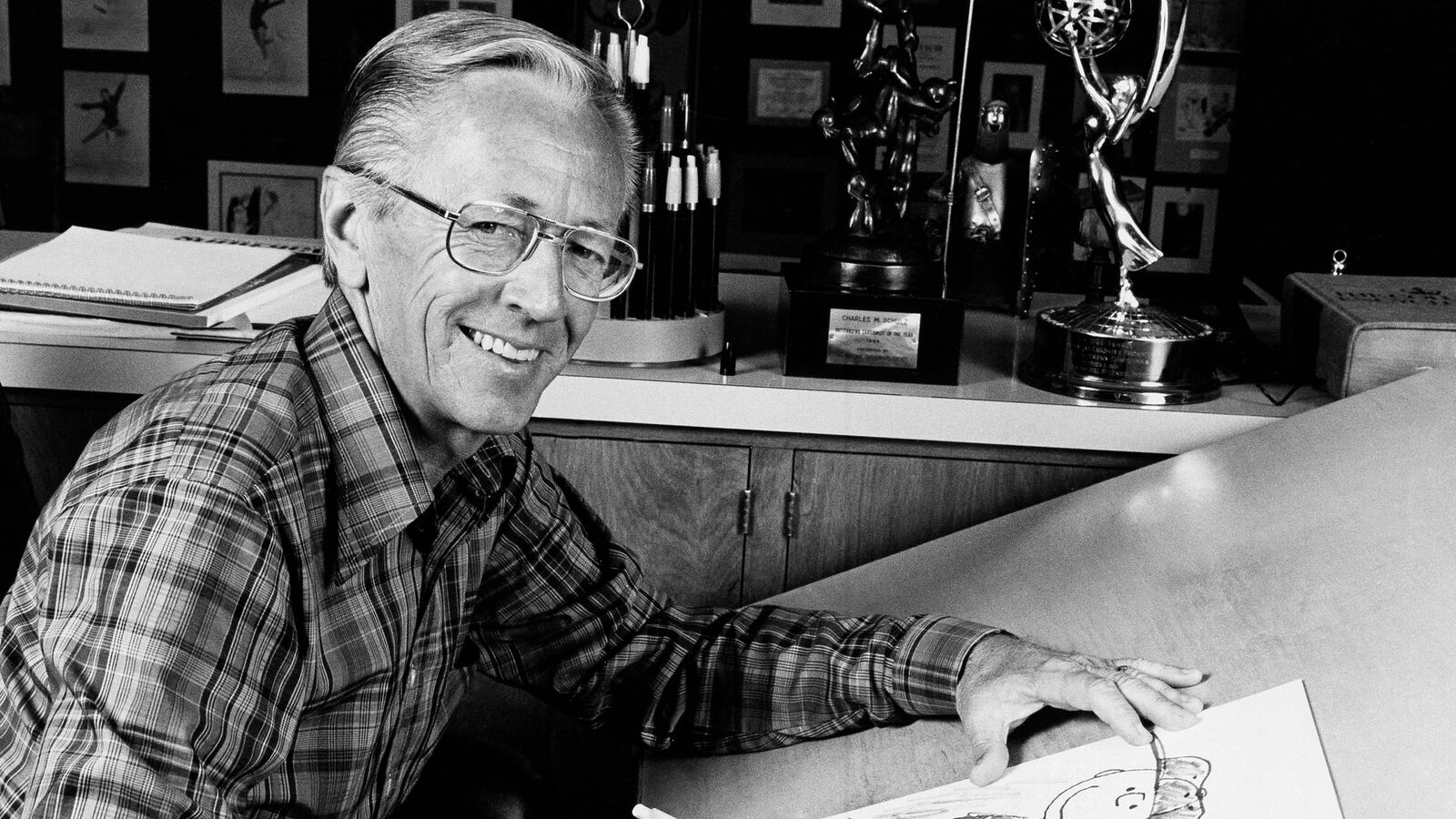

Schulz took us to his studio where he drew the cartoons. He had a work table that was angled up, and I saw a Sunday panel in progress. He had drawn all the squares for the story, and had sketched in some of the characters. None of them were saying anything yet, and they were only there in a light outline. My mother asked him something about where he got his ideas from. He answered her in a voice that was flat and plain, like the voice that a carrot might have. He hadn't really spoken to me since we arrived.

I looked around the room. It was large with a high ceiling, windows all around and a lot of light. There was a white carpet on the floor. The dog was still on the floor out in the entry. My good-natured sister was holding my father's hand, happily taking it all in. But I was so disappointed with everything that I suddenly started to cry.

I don't know what I expected exactly. I had been so excited to visit the home of my hero, the creator of so many hours of happiness for me – of companionship.

The Peanuts strip was a world that pulled me in and made me feel less alone. I felt that those characters were my friends. If only I could live inside that comic strip, I knew that I would find the happiness that I never had in the real world. Charlie Brown and I would be friends. Snoopy would say funny things and take me on adventures. Linus would let me hold his blanket. We'd have long discussions about things. No one would talk down to me, or tease me.

Schulz and his home were just more of the real world and I didn't like it. I expected him to entertain me, or at least to fill me with the good feelings that I had when reading Peanuts. I don't think I expected him to prop me up on his knee and tell me stories like my grandpa did before he died. But I somehow expected that just being with him would make me feel as good as reading his comics.

No one knew why I was crying and I couldn't explain it. Mrs. Schulz tried to offer me more sour lemonade in a paper cup. Then, the dog got up and came over and put his head against my leg. I sat down with him in the corner while the adults continued their adult talk about this and that. The dog's fur was soft. He didn't talk, or kiss me, or seem to be thinking much of anything, but I was happy there with my head resting against his.

Schulz had created a world that millions of people found escape in for a few moments a day, over a cup of coffee or a bowl of Cheerios. And for the lucky ones with Peanuts books, a world that filled long summer afternoons in treehouses, parks and summer camp cots. The Peanuts world, as many fictional worlds are, was more entertaining, more engaging, and – to some of us – more real than the day-to-day world.

This morning, I picked up the recently published biography of Schulz, whose real life seemed duller than a bag of flour. I learned that he suffered from depression, was moody, and not a particularly pleasant person. So maybe he himself didn't have much use for the real world and he created Peanuts as an escape for himself too.

And there he was, in the center of it, the anti-hero named Charlie. Optimistic, able to ride the tide of disappointment from each lost baseball game to the next without giving into despair. The greater the pain, the more beautiful the art, it has been said. The very thing that makes life unpleasant is that which propels the artist to reinvent everything for themselves, the way it could be. The way it should be.

Charles Schulz's beagle didn't know how to dance. But it knew a thing or two about comforting a sad human.

Charles Schulz died 13 years ago this week; he would have been 91.