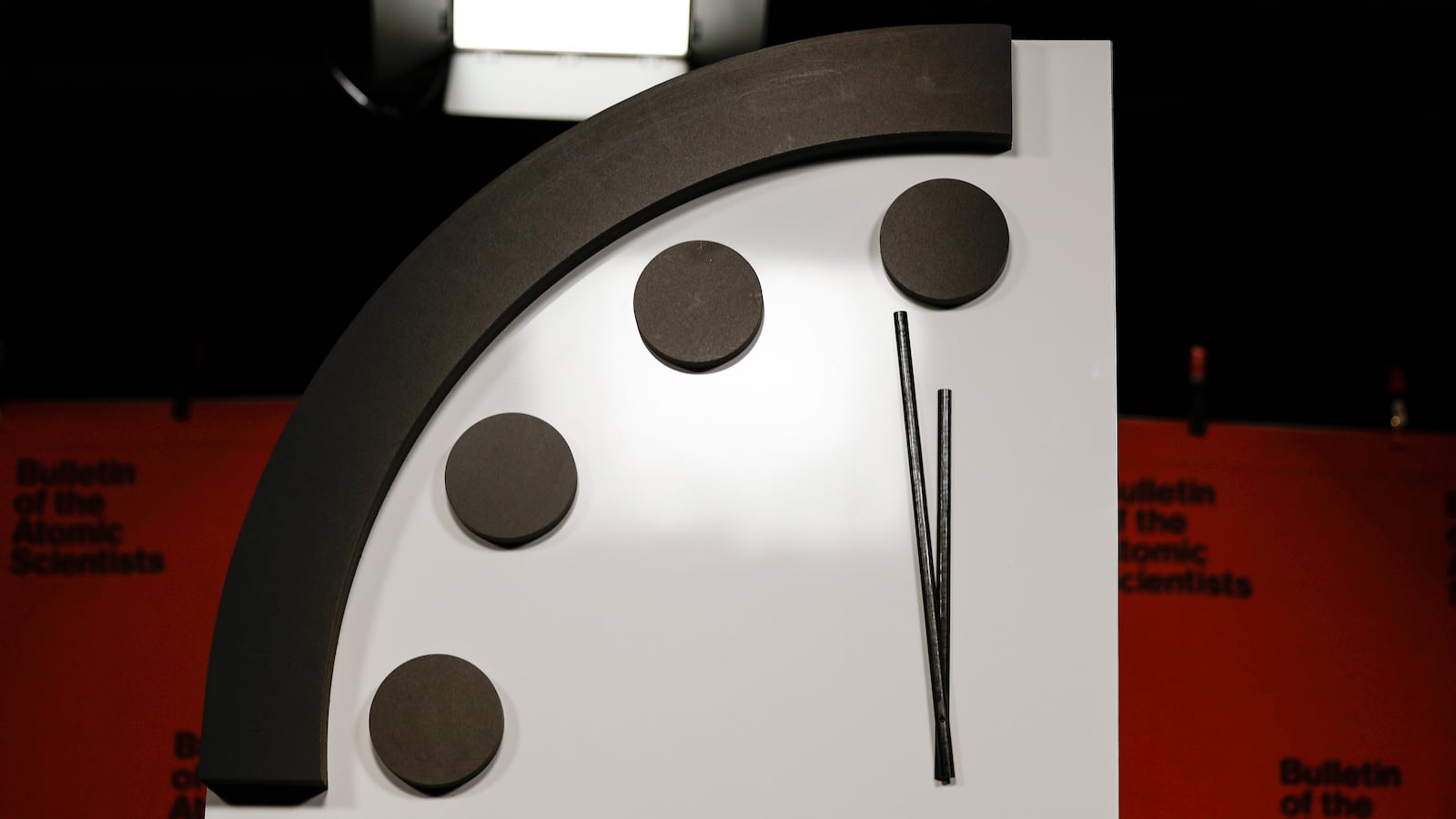

The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists announced on Jan. 24 that the Doomsday Clock is now set to 90 seconds to midnight—the closest it’s ever been moved to, and a sign of how dangerously close scientists think we are to initiating our own apocalypse.

The update was attributed largely to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which the Bulletin said creates compounding crises including the threat of nuclear destruction, a collapsing supply chain, and exacerbating climate disasters. The new time beats the previous record set in 2020 when the clock was moved to 100 seconds to midnight in the wake of the pandemic, and remained there until today..

“Today, the members of the science and security board move the hands of the Doomsday Clock forward, largely, but not exclusively, because of the mounting dangers of the war in Ukraine,” Rachel Bronson, president and CEO of the Bulletin, said in the announcement. “We move the clock forward the closest it has ever been to midnight.”

Members of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Siegfried S. Hecker, Daniel Holz, Sharon Squassoni, Mary Robinson and Elbegorj Tsakhia stand for a photo with the 2023 Doomsday Clock ahead of a live-streamed event on January 24, 2023 in Washington, DC. This year the Doomsday Clock is set at ninety seconds to Midnight.

Anna Moneymaker via GettyWhile certainly ominous, the Bulletin, a nonprofit organization dedicated to raising awareness about potential runaway dangers of technological advancements, describes the Doomsday Clock as simply a metaphor for global catastrophe. They hope that the clock serves as a call-to-action for the public, global leaders, and scientific community to reign in the tools and systems that can potentially destroy humanity.

That’d be a fine and noble goal… if it did any of that at all.

Instead of real action that pulls us away from doom, however, the response to the Doomsday Clock’s hands being moved back and forth is typically a lot of fear mongering and sensationalist headlines when they do update it. It’s not hard to see why. Look no further than the name “Doomsday Clock” itself. It’s spine tingling, hair raising, and stomach dropping. That’s the whole point, of course—but that’s also what makes the clock a futile relic.

The clock was initially created in 1947 by a group, dubbed the Chicago Atomic Scientists, was founded by researchers who worked on the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb. Shortly after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the group began publishing the Bulletin as a newsletter. Its cover depicted the Doomsday Clock to reflect how close they felt humanity was to destruction.

Or, as co-founder and inaugural editor of the Bulletin Eugene Rabinowitch put it in 1967, “The Bulletin’s Clock is not a gauge to register the ups and downs of the international power struggle; it is intended to reflect basic changes in the level of continuous danger in which mankind lives in the nuclear age, and will continue living, until society adjusts its basic attitudes and institutions.”

In other words, the Bulletin’s scientists are mostly using vibes to come up with their predictions. While there are a host of considerations taken into account including the opinions and analysis from a panel of Nobel laureates and scientists, it’s kind of a collective group guess at the end of the day.

“It’s not scientific,” Lawrence Krauss, a physicist and chair of the Bulletin’s Board of Sponsors, told The New Republic in 2018. “It’s a number that’s arrived at by a group of people who are exploring each of the questions, then having a huge amount of discussion, and ultimately a convergence on a number. And that number is frankly arbitrary. It’s not a scientific quantity.”

Over the decades, the clock’s proximity to midnight—which is supposed to signify calamity for the human species—has fluctuated pretty wildly, moving as far as 17 minutes to midnight in 1991 after the Soviet Union signed an arms reduction treaty with the U.S. before the U.S.S.R. dissolved later that year; and as close as 100 seconds to midnight in 2020 during the initial onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic, runaway climate change disasters, and the end of a nuclear treaty between Russia and the U.S.

The Bulletin’s scientists do have a point with the Doomsday Clock. Things, at best, feel very dire right now. At worst, things are just straight up a nightmarish hellscape for a lot of people. We’ve had a hard few years between the pandemic that won’t go away, a war in Europe threatening to pull the rest of the world into it, and compounding climate disasters that have claimed and changed the lives of people all over the world.

That said, the Doomsday Clock continues to be an exercise in futility, in which the Bulletin simply points out what many are already well aware of: It’s not going great, Bob.

Since its peak in optimism in 1991, the clock has been updated 11 times. With each announcement, we’ve steadily inched closer to the end times. We are no longer dealing in minutes until the end, but seconds. Rabinowitz once said that the clock was meant to “frighten men into rationality.” The message is loud and clear from the Bulletin: Do something soon, or we’re all screwed.

But really, there hasn’t been a case throughout history of the Bulletin that we can point to where it seems like the Doomsday Clock has done very much of anything in order to meaningfully call attention to the dangers facing the world.

Moreover, the Doomsday Clock might actually be doing the opposite of what’s intended and causing people to feel a sense of hopelessness with the state of the world. It should be no surprise that doomerism—the mindset that everything is hopeless and there’s nothing we can do in order to change catastrophe from things like climate change—and the Doomsday Clock would go hand-in-hand. After all, it’s in the name.

So why would anyone want to work towards a better future if we’re resigned to the fact that there won’t be a future in the first place?

That’s not a knock on the undoubtedly intelligent and well meaning people behind the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. It’s important that we have people in the Death Star constantly screaming about the outer vents that can be targeted with photon torpedoes.

But, much like the Bulletin’s mission to speak truth to power even when it’s hard to swallow, we need to be honest with ourselves and admit that the Doomsday Clock has run out of time.