I confess that I first opened this stocky book with a skeptical mind. What is there left to learn about Berkeley in the 1960s? Anyone with even a casual interest in that well-documented era has probably already read about the Free Speech Movement (FSM), the counter-cultural bazaar that was Telegraph Avenue, and the battle for People’s Park—or, at least, seen the videos on YouTube. The inhabitants of Berkeley were prominent combatants in every cause and conflict of the decade: civil rights and black power, women’s rights and environmentalism, hippies vs. straights, doves vs. hawks, radicals vs. liberals, and conservatives against left-wingers of every stripe. One could evoke the scent of tear gas and the din of angry rhetoric just by mentioning the name of the smallish city by the large and lovely bay.

The principal campus protagonists are still pretty famous too: the eloquent young radical Mario Savio, leader of the FSM, and the anxious liberal Clark Kerr, president of the California “multiversity” he struggled, vainly, to pacify. Moreover, every biography of Ronald Reagan describes how, in 1966, his repeated denunciations of “the mess at Berkeley” helped him claim the governorship of California in a landslide—and immediately won the hearts and minds of conservatives everywhere who saw the charismatic actor as their best chance to capture the White House.

Happily, Seth Rosenfeld, a veteran investigative reporter from the Bay Area, found a splendid way to refresh this familiar story—with tens of thousands of pages of previously unreleased FBI documents. And his narrative, while lengthy, moves along with vigor, enlivened by deft portraits of major and minor characters and the many battles, literal and figurative, they fought.

The files, in their entirety, took Rosenfeld 30 years and four lawsuits to pry out of the Bureau, and it was definitely time well spent. They reveal that J. Edgar Hoover and his zealous underlings viewed the ragtag Berkeley left as a dire threat to the American system and did all they could to discredit and destroy it. Because Kerr, who had once been an expert labor mediator, sought to compromise with radical students, Hoover denounced him as a coward and alleged, using charges he knew to be false, that he had once consorted with Communists. Early in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson told Kerr he wanted to appoint him secretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare—the key cabinet post at the height of the Great Society. But after Hoover divulged his smears to LBJ, the offer was quickly withdrawn.

Meanwhile, the FBI director’s obsession with Savio, whose stint as a leader was actually quite brief, became increasingly irrational. Early in 1968, long after the FSM had dissolved, Hoover fingered him as a “Key Activist” in a secret program which then dispatched agents to scour his bank statements, grill his employer, and track his movements on a daily business. By then, Savio was a danger to no one’s security but his own. He was struggling to hold down a blue-collar job at an electronics factory, plagued by depression and afraid he was “losing his memory.”

In the crusade against troublemakers at Berkeley and their supposed codependents, Hoover could always count on the zealous assistance, both covert and public, of a number of national celebrities and local politicians. The most significant of these, Rosenfeld shows, was none other than Ronald Wilson Reagan. Reagan’s close relationship with the FBI began early in the Cold War, when he exchanged “information” about pro-Communist actors, screenwriters, and union officials with agents who stopped by his home in the Hollywood hills.

For the next three decades and more, Reagan became, according to Rosenfeld, “one of the FBI’s best contacts ever.” He routinely passed along to the Bureau rumors about Communists in the film industry and frequently lauded the agency in speeches, press interviews, and on television. So appreciative was Hoover that, in 1965, he stopped his agents from questioning Reagan about his son Michael’s close and rowdy friendship with the son of a top Mafia chieftain, Joseph “Joe Bananas” Bonanno. Instead, the FBI boss ordered his men, as Rosenfeld puts it, “to confidentially warn the father about Michael’s ‘dangerous dalliance.’” Reagan, then considering a gubernatorial campaign, responded with gratitude and relief. A high-ranking G-man reported that “he [Reagan] realized that such an association and actions on the part of his son might well jeopardize any political aspirations he might have.”

Once he took office in Sacramento, Reagan worked diligently in tandem with the Bureau to drive the scourge of radicalism from the premier campus of the state university, and to buff his own image as a defender of Middle American resentments. He pressured the Board of Regents to fire Kerr, solicited reports from FBI informants, and met with Hoover in Washington to discuss what the aging director called “some of the problems which the Governor has had to face up at the University of California and his determination that law and order be maintained there.” If Hoover had lived into the 1980s, he might still have been trading the latest scuttlebutt about Mario Savio with the man who became president of the United States.

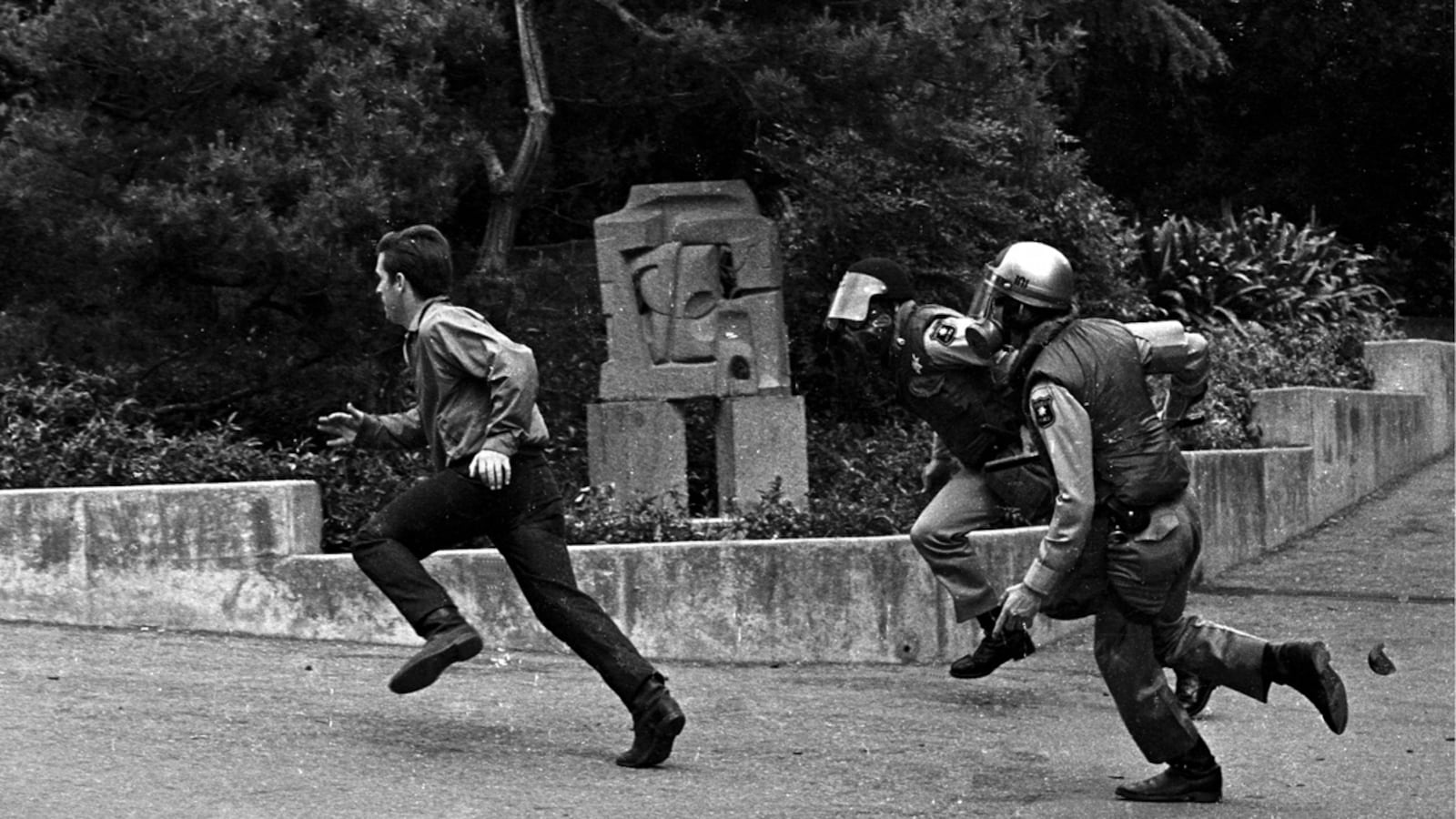

For all the rich evidence he distills, Rosenfeld ventures no opinion about the effectiveness of the FBI’s undercover campaign in the radical mecca by the Bay. The director was convinced that if he and his men, with aid of Governor Gipper, could stifle the “agitational activity at Berkeley,” they would “set up a chain reaction” that would set back student radicals all across the nation. But the decentralized, often anarchic nature of the New Left was nothing like the hierarchical organization of the Communist Party—Hoover’s rigid template of a “subversive” network. In fact, a defeat for protesters in Berkeley had little or no impact on radicals in Madison, Austin, or Cambridge. If anything, overt acts of repression, such as Reagan’s armed dismantling of People’s Park in 1969, provoked more young people into joining the cause.

Coyly, Rosenfeld chooses does not to identify whom he believes were the true subversives. Were they the Berkeley radicals who demanded the right to hawk literature for non-campus groups inside the gates of their public university and then protested, loudly but mostly nonviolently, against an unjust war their nation was fighting in Southeast Asia? Or were they the employees and allies of a powerful government agency who, in the name of protecting freedom, spied on, harassed, denounced, and sought to punish Americans, most of whom had committed no crime? If you think the answer is blowing in the wind, you really haven’t been paying attention.