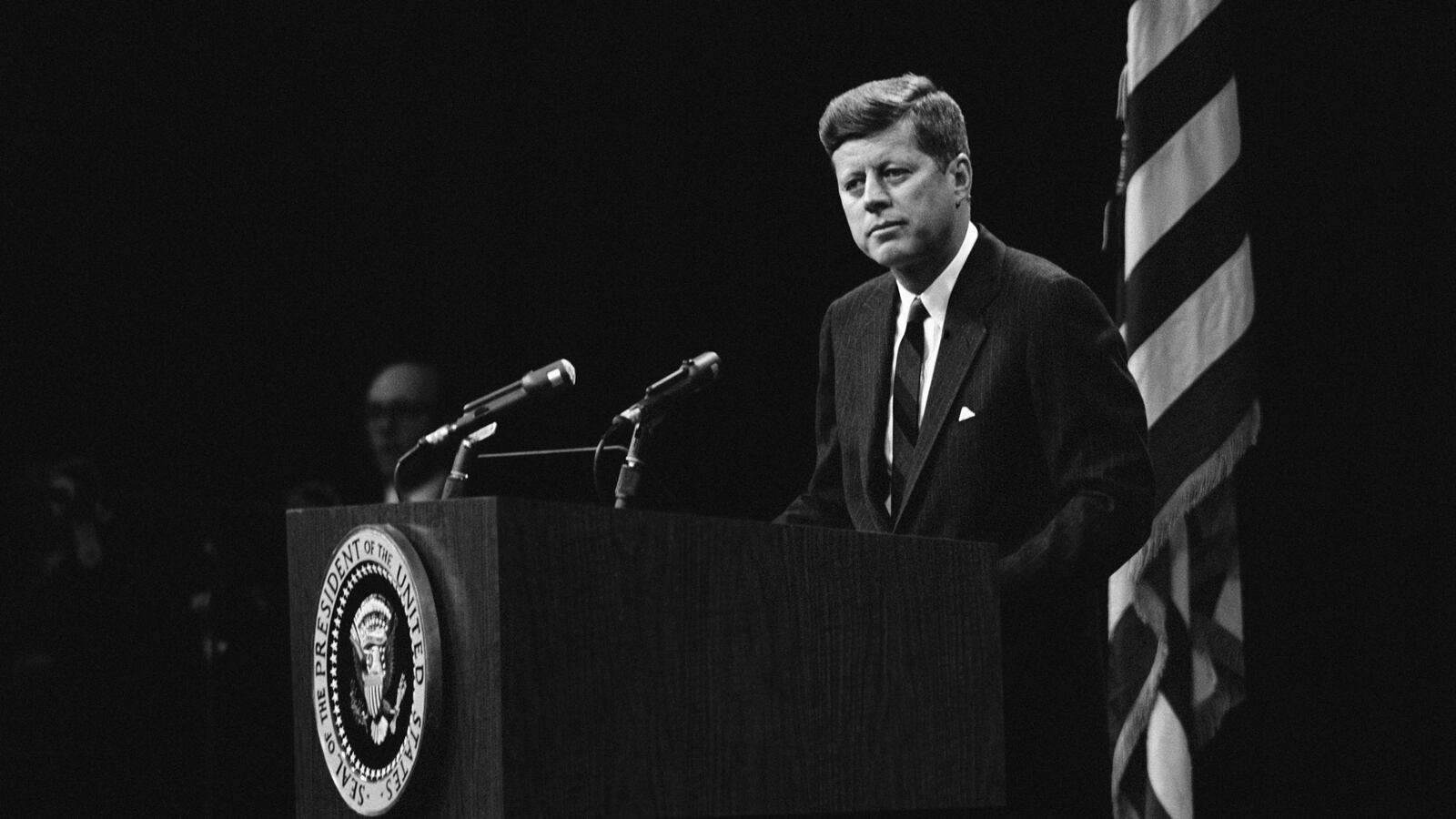

It will be 50 years this November since the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas. But the question of his legacy remains at issue and this fall will see the publication of a number of works treating the question, including one by former New York Sun editor Ira Stoll that audaciously attempts to lay claim to JFK as a conservative. Meanwhile, we have JFK’s Last Hundred Days: The Transformation of a Man and the Emergence of a Great President, in which author Thurston Clarke presents Kennedy as a liberal pragmatist who, for all his faults and failings, was on the verge of doing extraordinary and progressive things both overseas and at home.

Historical assessments briefly aside, when I think of John Kennedy I first recall the evening of the 1960 Democratic National Convention when our neighbor Mrs. D’Andrea wanted to know if my mom and dad, as Jews, could vote for a Catholic. Mrs. D’Andrea and her husband were Catholics and she apparently wanted some reassurance that if the Irish-Catholic senator won the nomination that night he would not fail to pick up the “Jewish vote” in November. As my parents told her, while Kennedy was not their first choice (which had nothing to do with his religion and a lot to do with his father, Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr.), they were Roosevelt Democrats and could never imagine voting Republican.

While my parents had voted for Kennedy and were deeply shocked by his death, they never struck me as JFK enthusiasts. Perhaps, as FDR Democrats, they were simply disappointed with his performance in the White House. The 1960 Democratic Party platform was one of the most progressive ever issued. Written like a manifesto, it recommitted the party to both Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man and “The Economic Bill of Rights,” which Roosevelt wrote into our national conscience. It declared that Democrats would act to create full employment; strengthen workers’ rights and protect consumers; improve the nation’s environment, public infrastructure, and cities; ensure decent housing, education, and health care; reform immigration; assure women’s equality; safeguard civil liberties; and actually end segregation. And yet Kennedy, after telling Americans to “ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country,” had proceeded to ask little of them. He seemed disinclined to fight for the things he and his party had projected.

Admittedly, Congress remained dominated by a conservative coalition of Republicans and Dixiecrats. But Kennedy himself did not try to rally Americans to his cause in favor of pushing the Democratic agenda. He was necessarily keen on foreign affairs, but his foremost domestic ambition was to stimulate even greater economic growth by enacting tax cuts for capital and the rich, which is why conservatives might lay claim to him. Only when liberals and labor and civil-rights activists seriously pressed him for action, and the 1964 reelection campaign began to loom on the far horizon, did he begin to energetically take up his party’s liberal projects. I may be wrong, but I recall more enthusiasm at home for President Lyndon Johnson than there had been for President Kennedy, due no doubt to LBJ’s apparent and amazing determination to enact the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts, build a Great Society, and pursue a War on Poverty that included expanding Social Security to include Medicare and Medicaid.

In JFK’s Last Hundred Days, Clarke argues that Kennedy had come to see both the Cold War and the domestic political situation in a fresh light in the wake of the 1962 missile crisis and that by the summer of 1963 he was starting to lay the political groundwork for realizing the promise he had represented and the promises he had made. Specifically, Clarke contends that Kennedy was planning to build on his success in securing the 1963 Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty by inviting the Soviets to be partners in going to the moon; to open secret negotiations with Castro in hopes of pulling Cuba out of the Soviet orbit (even as he continued to use the CIA and Cuban refugee groups to try to bring down Castro’s regime); to actually extricate the United States from Vietnam; and he was growing ever more hopeful that he could get Congress to reform America’s racist immigration law, enact the civil-rights bill he had proposed in the wake of the white-on-black violence in Birmingham that spring, and fund campaigns to combat poverty in Appalachia and elsewhere. In short, as Clarke presents it, the tragedy of November 22 was even greater than we have thought.

The author of 11 works of fiction and nonfiction, including The Last Campaign: Robert F. Kennedy and 82 Days That Inspired America; Ask Not: The Inauguration of John F. Kennedy and the Speech That Changed America; and Lost Hero, a biography of Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat and rescuer of Hungarian Jews during World War II, Clarke has written a real page-turner in JFK’s Last Hundred Days. Believe me, it makes for a great and stimulating vacation read. Sure, we know what’s coming at the end of the 100 days, but Clarke, deftly weaving together the private, personal, and intimate with the public, the political, and the-then-secret public and political, makes one want to keep reading to find out even more of the scoop.

Clarke recounts not only the sad death of the Kennedys’ premature baby Patrick, Jackie’s and Jack’s mourning and respective recoveries, and Jack’s own understandable obsession that there were folks eager to see him dead (perhaps even a conspiracy in the fashion of the film Seven Days in May), but also, retrospectively, the secrets of both Jack’s many health problems and his innumerable affairs with women such as the actress Marlene Dietrich; the wife of a German military attaché, Ellen Rometsch; and a couple of White House interns. And while he highlights how the Kennedys seemed to grow much closer to and warmer with each other in the wake of the loss of Patrick, he does not say that Jack would not have returned to his usual philandering ways—in fact, he hints at the possibility that he had.

As much as Clarke might want us to think and feel otherwise about Jack and Jackie, I did not find either one of them all that likable based on his accounts and narrative. I readily grasp their popular appeal and attraction. They were young, smart, beautiful people who seemed happy and good for each other and America. He was a war hero, and he had what people called “charisma.” She had an aura. But Clarke’s portraits of them are far from endearing.

Jack Kennedy didn’t just screw around a lot. He was a chauvinist and a misogynist, at times nastily so (see also the former White House intern Mimi Alford’s memoir). Moreover, his womanizing was so reckless as to not only threaten to destroy his presidency and the hopes of the majority of his fellow citizens (his marriage was surviving despite his cheating, which Jackie knew about), but also jeopardize national security. Rometsch was an East German refugee who had been a member of communist youth groups, knew the East German leader Walter Ulbricht, and still had family in the East, not to mention, as Clarke notes, was quite possibly a spy (and Kennedy had her deported back to Europe when things heated up and threatened a Profumo-like scandal). At the same time, Jackie herself comes across as nasty and selfish in her own way when, despite Jack’s not wanting her to do so, she accepts an invitation, only weeks after the loss of her child, to join her sister Princess Lee Radziwill on a Mediterranean cruise aboard the yacht of the Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, whom she would later marry in 1968.

More critically, I must dissent on Clarke’s argument that Kennedy was on the verge of becoming a truly great president. I agree that he would have beaten Goldwater in 1964, assuming that Goldwater was the candidate and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover or some GOP operative did not reveal JFK’s extra-marital affairs—the Greatest Generation would never have voted against what they had struggled for in the 1930s and '40s. I accept that Kennedy may even have come to seriously want to do all that Clarke projects him going on to do—indeed, he was testing the waters of the Cold War to see what might be possible. But could he have pulled it off?

Kennedy faced powerful opposition in Congress and what Eisenhower dubbed “the military-industrial complex.” And, for all of his talent as a speaker, he would have been a second-term president who had neither effectively cultivated the liberal and progressive spirit that had boosted him into the White House (a liberal spirit that Clarke’s narrative sorely discounts), nor fully learned, despite his capacity for conniving and deal-making, how to master Congress as LBJ had as Democratic Senate Majority Leader. (Clarke himself fails to criticize the Kennedy entourage for mocking and dismissing Johnson as incompetent behind his back.)

As informative and intriguing as I found JFK’s Last Hundred Days, and as tempting as it is to believe that Kennedy was on the verge of greatness, I cannot endorse Clarke’s argument. I not only find it hard to imagine that Kennedy could have succeeded in getting Castro to pull out of the Soviet orbit, making the Soviets our partners in space, and withdrawing the nation from Vietnam after the 1964 elections. I also find it very hard to believe he would have been able to redeem and advance FDR’s New Deal vision as effectively as Johnson did in 1964 and 1965. Politics, after all, is the art of the possible, not of the dream.