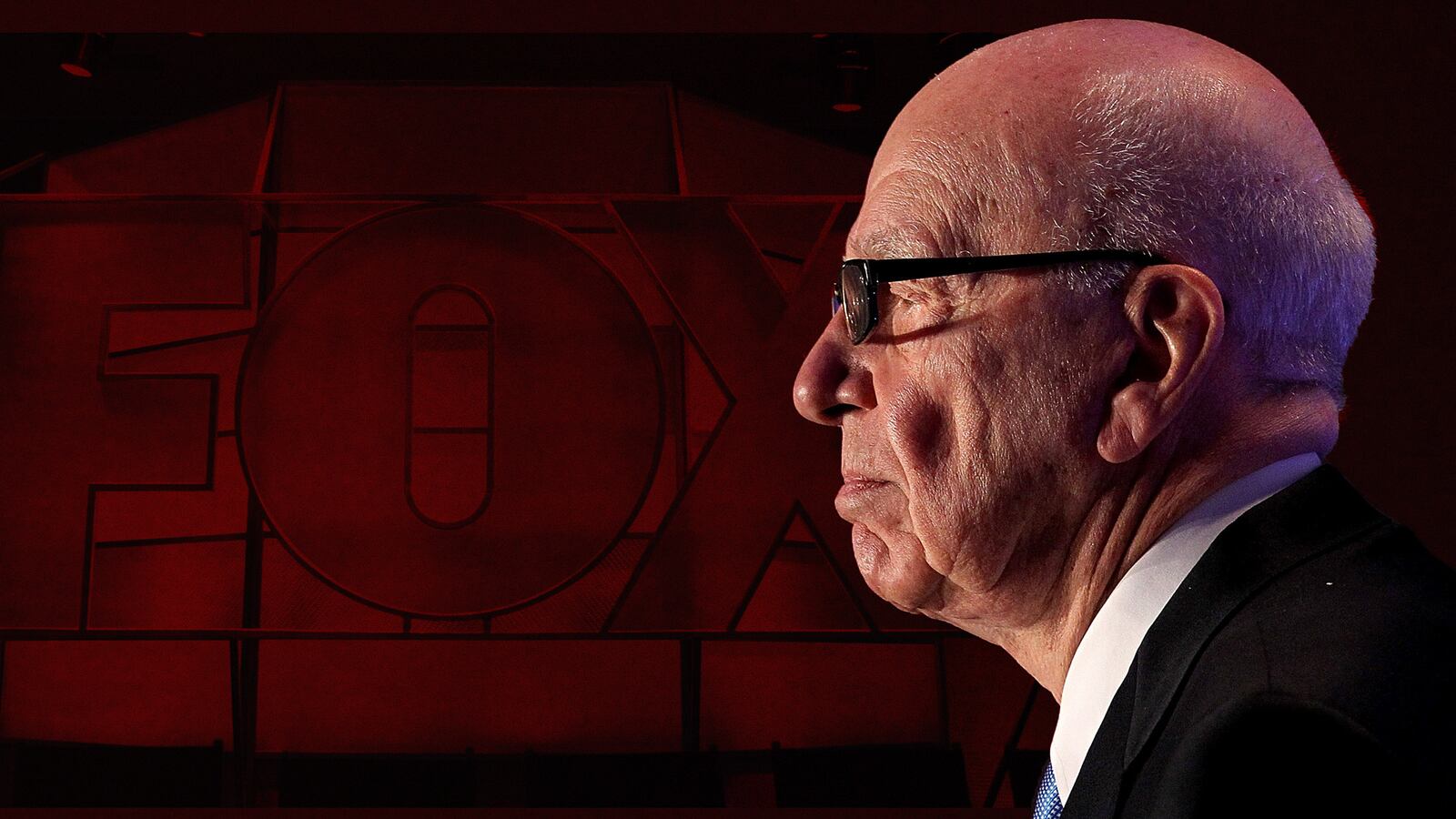

Last month Rupert Murdoch received an honor that, although obscure, meant a lot to him.

In a virtual ceremony, the U.K.-based nonprofit Australia Day Foundation gave him a lifetime achievement award, as he approached the age of 90. Murdoch, speaking from his English country estate, noted that his career began “in a smoke-filled Adelaide newsroom.”

Indeed, Murdoch’s journey to becoming a globe-straddling media mogul began in a very modest way in 1953 in the offices of the newspaper he inherited from his father, the Adelaide News.

Murdoch was fully conscious of how provincial Adelaide was, far from Australia’s powerhouse cities like Sydney and Melbourne. He had spent a while as an intern at the Daily Express in London, one of the world’s bestselling dailies, with a circulation of more than four million. In Adelaide the News was the underdog, with a circulation of only 75,000 against a well-funded rival with double that circulation.

Yet within two decades of that audition, Murdoch had set the foundations of a sprawling media octopus. Eventually he acquired the kind of power that inspired comparisons with fictional media barons, from Citizen Kane to Succession’s Logan Roy. All the while he used his power to bend politicians to his desire, at first in Australia, then, in Britain, and—his ultimate alliance—in the U.S., with Donald Trump.

But the empire’s underlying business model has changed. Murdoch’s power and influence were built on newspapers. Today that part of the business is in free fall.

This change shows up vividly in the financial results released Tuesday of Fox Corporation, the television side of the business. For the last six months, the Fox profit was $1.47 billion. Profits for News Corp, which includes the newspapers, was half of that, $765 million.

But buried within that number is the collapse of the printed news business, where revenue was down 33 percent and earnings down by a massive 40 percent, at $44 million. (The one exception is Dow Jones, including The Wall Street Journal, which is now treated as a separate business and showed a healthy 45 percent jump in profit.)

This highlights how important Fox News now is to Murdoch. It’s his main cash cow. Talking to analysts on Tuesday, Lachlan Murdoch, Fox Corp’s CEO, was bullish, pushing hard against the idea that with Trump’s defeat and disgrace the crazed bloviators of Fox News have lost their relevance, disaffecting their more moderate audience and not rabid enough for the rest.

He asserted: “We believe where we’re targeted to the center right, is exactly where we should be targeted. We don’t need to go further right. We don’t believe America is further right. All of our significant competitors are to the far left.”

That doesn’t take account of two fundamental weaknesses. Advertisers have been bailing from the network after it echoed the “stop the steal” loonies—the benching of Lou Dobbs was an immediate result of that. And the Fox demographic, older and mostly white, is similarly lacking in advertising appeal. (For the first time since 2000, Fox came third, behind CNN and MSNBC, in the 25-54 age group, where its audience dropped by more than half.)

Looking at the new figures, media analyst Peter Kreisky, a veteran Murdoch-watcher, told The Daily Beast: “Fox is between a rock and a hard place with nowhere to go.

“What defined it originally as far right is now center right. To its right is a new constellation of extreme right-wing news outlets, Newsmax, One America News, Breitbart, and all the conspiracy-theory nutjobs. Fox’s greatest danger is to become just another conservative channel without the sharp identity it once had.”

How and why did it end this way? What were the qualities and motives that drove Murdoch on his amazing trajectory from an Australian backwater to global power and notoriety?

It originates in an instinct that was natural in Murdoch’s approach to journalism. He believed that news, like gold, was a commodity, and if mined and packaged in a distinctively basic and sensational form it became pure gold. That’s why the vehicle for his empire was named News Corporation, and why his eventual mother lode was named Fox News, even though it wasn’t actually news that was its lure.

Murdoch’s breakthrough tabloid, which became the accelerant for his print empire, was the Sun, relaunched in London in 1969 under Murdoch’s ownership. But the move that took that business to a new level came in 1986, when he broke the stranglehold of the print unions by moving his papers from the old hot metal technology to computerized production at a new plant at Wapping, in East London, miles from Fleet Street, the ancestral and eponymous center of the British press. This step caused much bitterness at the time, but by transforming newspaper economics it saved an industry that had been nearly bled to death by corrupt union bosses.

On the strength of that one move, the market value of Murdoch’s four London papers rose from $300 million to $1 billion. He was printing 33 million copies of his papers every week and his annual profit soared 85 percent to 34.5 million pounds.

But by that time, Murdoch had fixed on America as the pinnacle of his ambitions and Hollywood as the great prize. First, he made an abortive attempt to buy Warner Brothers that ended with him making a profit of $40 million on Warner shares. Then, in 1985, he began a series of moves that eventually gave him control of Twentieth Century Fox and, at the same time, he bought seven TV stations and coupled them with Fox to create a new national network to challenge the legacy trio of CBS, NBC, and ABC. Suddenly the Australian renegade was both a Hollywood magnate and a visionary who understood the synergy of movies and TV.

However, the rapid expansion and change of his own status stretched Murdoch’s financial resources. For a while that didn’t seem to matter. He had the Midas touch.

By 1990, News Corp controlled more than 70 percent of the press in Australia, nearly 40 percent in the U.K., the Fox studios in Hollywood, a fast-growing U.S. television network, as well as some American magazines and the New York Post.

But as he consolidated his world media empire, Murdoch had taken on a pile of short-term debt. He could have financed his growth by selling stock—plenty of investors would have leapt at the chance. But Murdoch and the family held 45 percent of the shares and did not want to dilute their holding.

This had worked well until mid-1990, when the international banking system went suddenly into a tailspin. Murdoch was caught with $2.5 billion in short-term debt—six times that of the previous year.

News Corp had good standing with the banks. Murdoch had always met every payment on schedule and he was established as a great deal-maker. But now the banks were in a panic. And it turned out that the News Corp loan chain extended to 146 financial institutions and the money was in 10 different currencies.

A lot of debt was due to be repaid in the next nine months and, once they saw the degree of News Corp’s exposure, the banks were getting cold feet about rolling over the loans. The Financial Times, looking at the numbers, said News Corp’s situation was “somewhat terminal.”

The business was saved by Ann Lane, a vice president of Citibank, News Corp’s largest creditor. As it happened, Lane had just finished restructuring another business on the point of unraveling—Donald Trump’s. Lane put together a team who tracked every News Corp loan to its source. It took three months to keep all the banks on board. There were a number of close calls. But in the end Murdoch’s chaotic finances were simplified and brought into line with the size of business it now was.

The importance of this near-death experience on Murdoch’s approach to his business cannot be overstated. Whatever the political influence he gained as a result of his newspapers and TV networks, the ultimate size of the empire was always going to be limited by his insistence that it remain essentially a family business, where he could always have hands-on control and place his children as his successors.

And that dynastic model became increasingly out of kilter with the future development of global media. In the 21st century, new media empires grew that straddled Hollywood studios, cable TV, the internet, and social media. At the same time, Google and Facebook sucked advertising away from print, wrecking the standard newspaper business model.

Murdoch has never shown a sure touch in trying to adapt, in pairing news content with digital platforms. In 2011 he launched The Daily, the first digital newspaper, designed for the launch of Steve Job’s iPad. It was killed a year later after losing $30 million.

Murdoch explained that it “could not find a large enough audience quickly enough to convince us that the business model was sustainable.”

Critics said that The Daily was a good idea crippled by a business model suited to print and too dependent on advertising revenue. They pointed to one of his old newspaper rivals, the London Daily Mail, that invented a new form of digital tabloid, MailOnline, and turned it into an international click-bait phenomenon—something that Murdoch could and should have done with the Sun.

And when it came to Murdoch’s hold in Hollywood, he was confronted by the most potent disruptor of the entertainment business, Netflix. The marriage of movies and streaming was pursued by every company with a stake in content, either in movie and television archives or as producers.

Only publicly traded media conglomerates not restricted by a dynastic family shareholding are able to play in this league, which is why, in 2018, Murdoch had to sell Twentieth Century Fox to Disney for $71 billion (not that bad when you consider that he originally paid $575 million for it!).

In the jargon of Wall Street, the word that terminated the expansion of the Murdoch empire was “scale.” Murdoch accepted that he lacked the size to stay in the streaming game. Companies like Disney and Comcast, run by corporate managers, not proprietors, need levels of funding that come with giving Wall Street sway in the boardroom, something that Murdoch has never tolerated.

Murdoch is a complex person, but people who worked for him over several generations agree on one thing: His business comes before anything else in his life. He’s not ideological. His editorial bias goes to wherever he can capture a market. Fox News, as Harvard researchers pointed out, is “a social movement orchestrator.”

The Fox News audience coalesced as a white tribal reaction to Barack Obama’s election. Then it readily fused with Trump’s base to a point where the two were indistinguishable. Murdoch himself went all-in with Trump, after earlier doubts, giving him the kind of White House access he had always craved.

He had always lusted after CNN, believing its international reach was under-exploited. When AT&T took over CNN’s owner, Time Warner, he made two attempts to buy the network, enlisting Trump’s support, but failed.

In the end, going with Trump was a bad bargain. He should have read Rick Wilson’s message: Everything Trump touches dies or, in the case of Fox News, turns to crap. Without realizing it, Murdoch became Trump’s puppet. Fox News was complicit in the catastrophic response to the pandemic and equally complicit in the Capitol insurrection. Murdoch cannot escape that judgment.

The family dynasty, so important to Murdoch, is terminally ruptured by the disgrace of Fox News. James Murdoch, once the most ambitious and accomplished of the heirs, bailed last year, citing “disagreements over certain editorial content” and has since reinforced his horror at the network’s descent.

Of the Murdoch children, only Lachlan “Jackaroo” Murdoch, Rupert Redux, remains steadfastly loyal to the Fox News mission. Now the two of them are doubling down and, in doing so, signing off on the legacy of Murdoch’s empire, and it’s ugly.