When I was a little girl, I loved and looked up to many females: Melissa Joan Hart, the Olsen Twins, the Spice Girls. But more than any, I loved Eloise. And at 25, I still do.

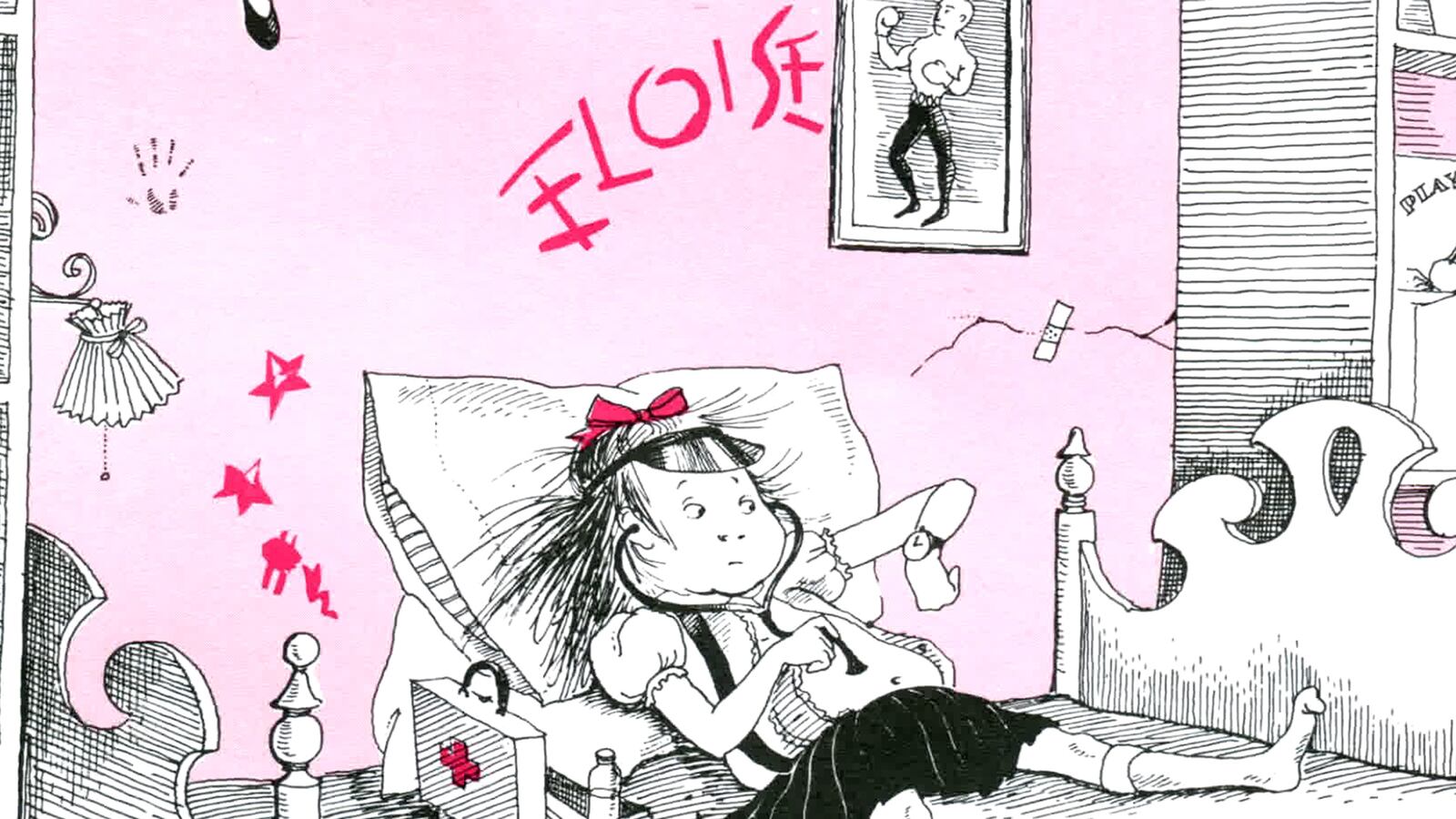

Unlike the other ladies in that litany, Eloise is not an actual human. The 6-year-old girl who wreaked havoc on New York City’s Plaza Hotel was the creation of author Kay Thompson and illustrator Hilary Knight. Yet, 60 years since her 1955 debut in Eloise: A Book For Precocious Grown-ups, Eloise has been a hero to generations of girls—and for good reason.

Eloise is a force of nature whirling about the Plaza. She is in constant motion, whether messing with hotel thermostats, irritating the hell out of her exhausted “rawther” British nanny, or hobnobbing with her never-seen mother’s lawyer. (By the way, Eloise’s father is never even acknowledged.) But instead of being a latchkey child, she parties it up at the Plaza. No wonder Sarah Ferrell wrote in The New York Times of Eloise, “Today she’d probably be on Ritalin.”

To the girls who read her books and the women those girls have become, Eloise is implausibly adorable. I don’t mean “adorable” in the cutesy, precious sense, but in the way you cannot help but adore her gumption, her humor, her total joie de vivre.

Because we who are among the cult of Eloise hold the little girl in such high nostalgic esteem, perhaps It’s Me, Hilary: The Man Who Drew Eloise, which premiered on HBO Monday, March 23, was bound to disappoint. The focus on Knight, the man who is too often overlooked for bringing the rambunctious child to life, is long overdue. The slivers of insight into his artistic aesthetic and professional endeavors are great. Unfortunately, there just isn’t enough about him or, for that matter, Eloise.

Produced by the Girls team of Lena Dunham and Jenni Konner, the documentary is meant to be a loving homage from the grown-ups whose childhoods were so influenced by Knight’s work, and the opening minutes feature heavy hitters, from Fran Lebowitz to Mindy Kaling, speaking of Eloise with admiration.

An involuntary eye-roll passed across my face when Dunham playing with what looks like a sparkling gold pom-pom on her head flashed across the screen. There’s way too much Dunham in It’s Me, Hilary, which is the prime flaw of the documentary. I say this as someone who admires Dunham and her work. But with someone as dynamic and delightful as Knight and a mere 35-minute running time, get out of the way and let the man have the whole spotlight.

It’s Me, Hilary does a solid if brisk job of shining a light on Knight’s other artistic endeavors. We travel through his Long Island home and are privy to his man-made moat, the beautiful posters he illustrated for Broadway musicals, and his whimsical, childlike perspective of the world.

However, scant attention is paid to his adult personal life. One of his nieces says in passing that she grew up always knowing he was gay, and that is the only mention of his sexual or romantic history. It was a glaring topic not to delve into, and I imagine Knight was loath to discuss his sexual orientation. Au contraire.

I spent 30 minutes on the phone with the 88-year-old illustrator, who spoke with utter candor and an acerbic charm about any and everything asked of him.

“I came out of my mother as gay as anyone could possibly be, and I would love The Daily Beast to print that,” he tells me when I ask if he wanted the documentary to steer clear of his homosexuality. “I can talk about it for six hours if you have the time.”

Knight has a highly nuanced view of homosexuality after living through the most significant decades for LGBT social and political advancement. He takes a rather laissez-faire view. “It was simply not discussed,” he said of growing up and being gay. “There was not a phrase ‘gay.’ Today you say ‘gay.’ There's too much of it. It’s part of life. Just sit back and enjoy it. Don’t act like it’s something that needs to be discussed.”

The artist mocks people who have made it a point to come out publicly later in life. “All of these people—I don't name names—someone who has been around for years, he just came out, and I thought, ‘Jesus Christ,’ and I thought ‘Why?’” For someone who has been out his whole life, witnessing these can seem like a big deal over nothing. “No one had any doubts about me, so why should I talk? I’ve never hidden it.”

This is not to say that Knight is oblivious to the significance of gay rights. “All of the marriage things are great, and it’s going to take a long time still and for a lot of people to accept it, and it’s wrong,” he says. “It’s important for people to accept it and forget it. It’s going to be around and always has been around and thank God for it. The world would be a much duller place without it.”

Knight was also more than happy to tackle one of the juiciest Eloise rumors: Is Eloise actually little Liza Minnelli? Many believe that beloved little girl at the Plaza with the absentee mother and the nonexistent father is actually based on Liza with Z. After all, Thompson was Judy Garland’s close friend and Minnelli’s godmother.

“There is very good basis for that, and Liza knows it because Liza was very much around as a little 6-year-old,” Knight said. “Kay had to have absorbed things about Liza that made their way into Eloise, but Kay always said, ‘It is not Liza. It is totally me. It is me, Eloise.’”

Perhaps only the most devoted Eloise fans would care about these little morsels of insider info, but the absence of them in It’s Me, Hilary is disappointing.

This is not to say that It’s Me, Hilary doesn’t offer its own insight into the saga behind the unflappable little girl. Thompson and Knight had an ugly split in the midst of composing the fifth Eloise book, Eloise Takes a Bawth. In fact, Thompson apparently nixed the original publication right before it was supposed to hit the press in 1964 (it was eventually published posthumously with Knight’s drawing and additional text from Thompson’s friend, Mart Crowley, in 2002). From Knight’s view, Thompson became increasingly controlling, literally pushing the pencil around in his hand as he drew and pasting rubber cement over his work.

According to Knight’s account in the documentary, Thompson essentially duped him into signing over his rights to Eloise and was banned from drawing Eloise professionally without clearing it with Thompson’s estate (she passed away in 1998). “It was demoralizing not to be able to continue drawing Eloise,” he says in It’s Me, Hilary. “I always have to have the permission of the estate,” he confirmed to The Daily Beast.

Knight seems to be filled more with a desire to ensure Eloise’s place in history rather than any animosity toward Thompson. It’s not as if his professional divorce with Thompson ended his artistic career—far from it. Knight proceeded to rack up an illustrious resume, illustrating not only over 50 books—and authoring nine of them—but also album covers, Broadway posters, and magazines, including Vanity Fair. He is even working on a new project called Olive and Oliver, which will be based on “my own favorite character, which is myself,” he says.

But Knight is deeply appreciative that people still have Eloise in their lives. In both It’s Me, Hilary and our interview he says he has nothing but gratitude toward Dunham for “reintroducing” Eloise. “What people may have forgotten, people will know about it,” he says of the documentary.

It’s a bit shocking how convinced Knight is that Eloise has all but disappeared from our hearts and minds. When our interview ends, I hang up the phone, and am a little sad that Knight doesn’t seem to realize we’ve never stopped loving Eloise, or him.