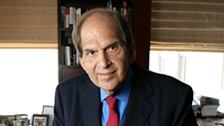

Bruce Wasserstein, the Wall Street M&A titan who died unexpectedly Wednesday at the age of 61, lived an extraordinary life of many chapters that together provide invaluable lessons for a Wall Street community still shaking from the financial calamities of the past few years.

Although risk-taking is a Wall Street hallmark, in truth, the business is full of tremendously risk-averse people who are more comfortable playing with other people’s money. At first, Wasserstein was in that camp, but as he matured and his M&A advice became less tried and true, he began to take risks with his own growing fortune. He was the only head of a Wall Street firm who was also the head of his own separate unaffiliated private-equity firm—something unheard of before him and unlikely to be repeated. And in a system that appears to have become undone because of a lack of focus, he embodied it. While Wasserstein may be remembered for his strong-arm M&A tactics and his “dare to be great” speeches, his greatest legacy may be one not of destruction but of preservation. By keeping Lazard’s time-tested business plan of providing only M&A advice and asset-management services to its clients—a business philosophy created by Lazard’s one-time patriarchs André Meyer, Felix Rohatyn, and Michel David-Weill—Wasserstein showed the rest of Wall Street that business can be done profitably and relatively risk-free, without bringing down the capitalist system and costing taxpayers $12 trillion and counting. Lazard has never taken a dime of TARP funds nor taxed our system in any way.

Wasserstein made more money from investment banking than any man on the planet.

The first chapter of Wasserstein’s life opened in Brooklyn, New York, where Bruce was a precocious Yeshiva student known for making up his own rules at Monopoly. He discovered early on that a lot more houses and hotels could be purchased by borrowing from the bank, even though that idea was not part of the game, at least the way the rules were written. His father owned a ribbon-manufacturing business in Lower Manhattan. Slowly but surely, the business thrived, allowing the family to move from Brooklyn to the Upper East Side when Bruce was a teenager. He enrolled at the now-defunct McBurney School, then a West Side institution from which Lazard’s Rohatyn also graduated. Soon enough, Wasserstein was testing the rules again, and after he wrote some silly headlines for the school newspaper, of which he was the editor, the school’s headmaster kicked him off the paper.

At 16, Wasserstein left New York for the University of Michigan, where the somewhat slovenly and unkempt but brilliant young man wrote revolutionary screeds for the university’s daily newspaper. As a reporter for the Michigan Daily, he covered the uprisings in Berkeley as a campus correspondent. After Michigan, Wasserstein went to Harvard, where he was one of the first to enter a joint program in business and law. He also married the woman who would become his first wife, whom he had met at Michigan. (Wasserstein would eventually marry four times.) During his postgraduate traveling Knox Fellowship to Cambridge, England, he studied British merger law while his fellow students worried about America’s involvement in Vietnam.

When he returned to New York from England, Wasserstein went to work at Cravath, Swaine & Moore, the preeminent law firm, where almost immediately he impressed senior partner Sam Butler with his energy and his rare brilliance in M&A tactics and strategy. He also impressed Cravath’s clients, as well as Joe Perella, then the lone person in First Boston’s fledgling M&A group. Perella quickly latched on to Wasserstein and figured they would make a dynamic duo. Perella was right. They became a pair of M&A insurgents.

Wasserstein was one of the first lawyers to leave law for the far more lucrative investment-banking business. At that time, Lazard, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley dominated the mergers and acquisitions business. At First Boston, Wasserstein and Perella had to offer clients something different, and that difference turned out to be Wasserstein’s technical and strategic brilliance. He pioneered takeover techniques—such as the "street sweep," the now-outlawed step of buying the stock of a target at will in the open market before launching a deal—and the use of “bridge loans” as a way to help corporate raiders buy companies they otherwise couldn’t afford. He helped corporate raiders such as T. Boone Pickens and Ron Perelman win deals. Wasserstein’s M&A hijinks, however, came a cropper when he advised Robert Campeau, a previously unknown Canadian real-estate developer, to buy first Allied Stores Corporation and then Federated Department Stores, using other people’s money, including millions from First Boston. When Allied and Federated filed for bankruptcy, the together comprised the largest bankruptcy filing of all time. Creditors lost billions. First Boston lost hundreds of millions of dollars itself.

The end of Wasserstein’s career at First Boston came when he made a power play to become head of the bank. He failed, but triumphed by starting Wasserstein Perella & Co. with a bunch of First Boston’s superstars. But business started to get tougher at Wasserstein Perella in the aftermath of Wasserstein’s failed advisory assignments. The once-fawning financial press turned on him, and he became the brunt of jokes and less than flattering articles. In a cover story, Forbes magazine dubbed him “Bid ’Em Up Bruce.”

When his five-year contract was complete, Perella quit the firm, and left to his own devices, Wasserstein became more and more difficult to work with. The firm was losing steam, and the rumor was it could no longer meet its payroll. But the ever-canny Wasserstein figured out a way to sell the firm at the top of the market to Dresdner Bank, for $1.4 billion in 2000. He personally pocketed $600 million of profit. But soon he alienated his bosses in Germany an was looking for a way out. Allianz, which by then had bought Dresdner, paid Wasserstein his full $75 million three-year contract before the end of his first year to be done with him.

Shortly after September 11, 2001, Lazard patriarch David-Weill, who had tried twice previously to hire Wasserstein, finally convinced him to join Lazard as CEO.

Wasserstein quickly resurrected Lazard—and would soon buy out David-Weill to take control of the firm. Wasserstein’s $30 million investment in Lazard rose in value to around $600 million, as the firm’s stock spiked up after it went public. Indeed, Wasserstein made more money from investment banking than any other man on the planet who did not inherit it first.

Wasserstein mysteriously disappeared from the firm in early 2006 and came back to the office in May looking noticeably thinner and unwell. Lazard never explained why. That year his sister Wendy, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, died of cancer. Wasserstein decided to adopt her child, whose birth became a public affair thanks to Wendy’s writing and the fact that she never disclosed the identity of the father. In recent years, Bruce Wasserstein has shied away from much involvement in deals, with the noticeable exception of his recent participation in Kraft’s still-tentative efforts to buy Cadbury.

Today, Wall Street would be a very different place if firms looked more like Lazard and Greenhill and less like Bear Stearns and Lehman once did. By keeping Lazard’s original focus, Wasserstein has left an enduring legacy that the rest of Wall Street would do well to emulate.

William D. Cohan, a former senior-level M&A banker on Wall Street, is the author of The Last Tycoons: The Secret History of Lazard Freres & Co, and his new best seller House of Cards: A Tale of Hubris and Wretched Excess on Wall Street.