Who is Jim Thorpe?

Men of a certain age are struck dumb for a couple of beats by the question. Then they sputter, “Jim Thorpe!” As if the greatest multi-sport athlete of modern time was, simply, God. A younger group—male and female, post Title IX—know about him because, universally, they have each once written a sixth-grade book report on “Jim Thorpe—Native American Athlete.” A third demographic looks blank: “Jim who?”

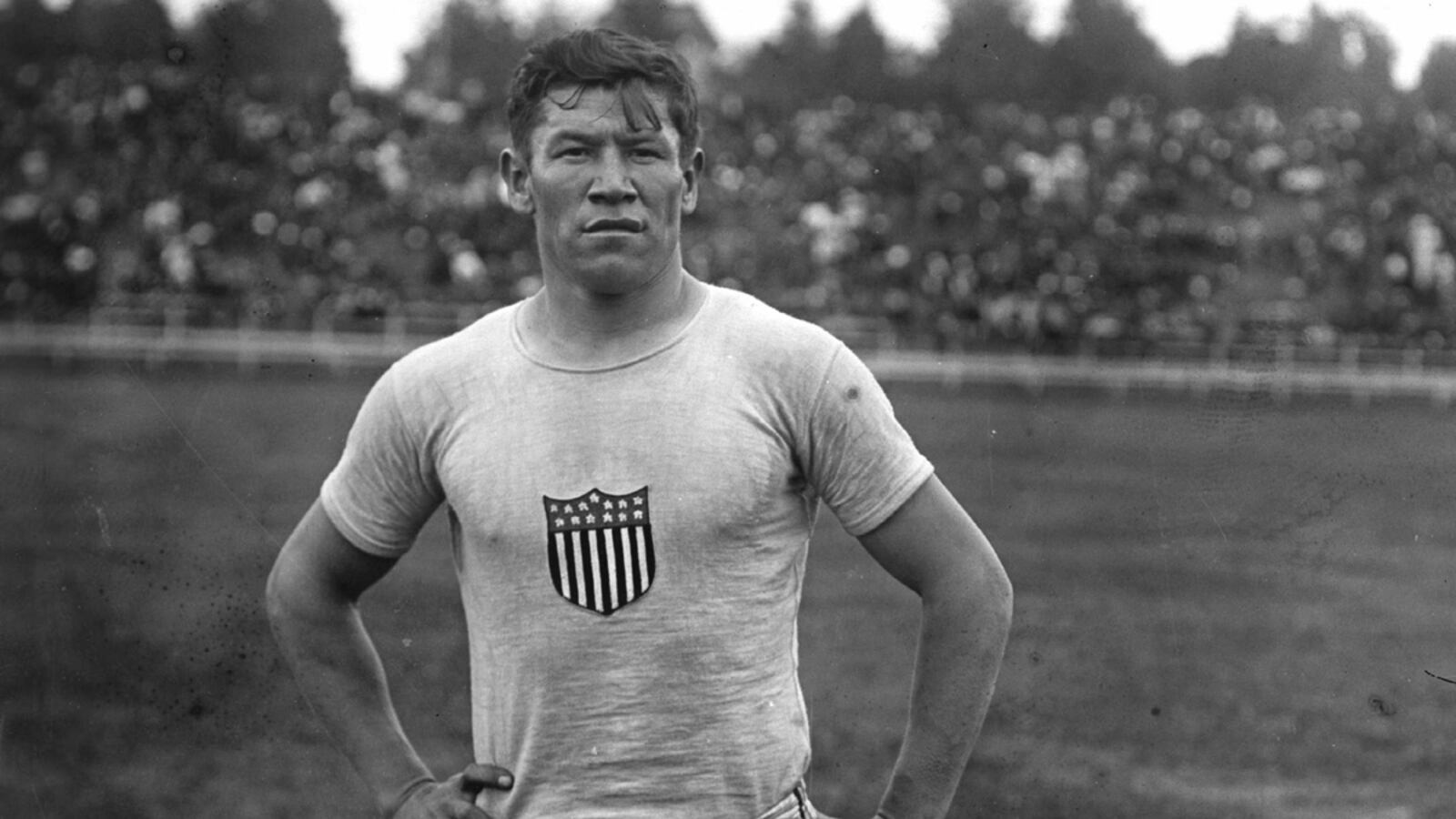

Monday, July 15, 1912, was the last day of the Fifth Olympiad in Stockholm. Thorpe had already won the five-event classic pentathlon and now triumphed as the winner—by another huge margin—of the first ever ten-event decathlon. The awestruck King of Sweden, presenting him with his two gold medals and challenge trophies, famously said: “You, sir, are the most wonderful athlete in the world.”

A century ago those multi-sport events were revered as the ultimate test of the strength, speed, and stamina of the true athlete. The man who won both of them for the first and only time (the classic pentathlon was dropped after 1924) was the first modern Olympic superstar.

Pre-doping, pre-systematic training, pre-everything—Thorpe is still right up there in the Olympic Pantheon. One example among several: his time in the decathlon 1,500-meter run—4 minutes 40.1 seconds—was not beaten until the 1972 Games. Today’s top Olympic decathlete, Bryan Clay, clocked in at only one second faster than Thorpe.

He was the sports sensation of the world, setting the first gold standard of athletic performance. In our sports-obsessed time, how could everybody not know that? The answer is complicated and says a lot about how we remember our heroes—or don’t.

Thorpe, 25, returned to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania that fall of 1912 to lead its famed football team, coached by Pop Warner, to a 12-1-1 record. The epic defeat by the Carlisle Indians of the West Point cadets nailed his reputation as one of the greatest collegiate football players.

That, and the fact that he may have been college football’s first 2,000-yard rusher, running 1,869 yards on 191 attempts—more yards than O.J. Simpson would run for USC in 1968. There were no official collegiate records in 1912, only newspaper accounts and they are missing for two games Thorpe played in. It’s more than likely Thorpe ran at least those 131 yards.

But the glory didn’t last. Six months after his triumph in Stockholm a newspaper revealed that the world’s greatest amateur had played minor league baseball for pay in 1909 and 1910. The Olympic hierarchy saw him as having shamed their new and struggling modern movement. Because of its international scope and impact his fall from grace has been called the mother of all sports scandals.

Thorpe was immediately defended around the world as a scapegoat to the elitist—and already hollow—code of amateurism. He was embraced as a people’s hero, the ordinary man who had done something extraordinary, the outsider who got screwed by the big boys.

The rest of Thorpe’s life, from 1913 until his death in California in 1953, is usually summed up as one, long, sad decline. In fact, despite two failed marriages and a drinking “problem” no worse than that of most athletes in that hard-drinking era, Thorpe accomplished much.

He turned professional, big-time, in 1913, signing with the New York Giants baseball team, the Yankees of their day. After a rocky few years playing the one sport that did not come easy to him, by 1919 he was hitting as well as Ty Cobb and Joe Jackson.

In 1915 Thorpe started also playing and coaching the “reptile sport” of professional football in Canton, Ohio. By 1920, largely thanks to the attention his fame and a string of championships brought to the game, he was voted the first president of the organization that, two years later, would change its name to the National Football League. Until the late 1920s he continued to alternate playing baseball and football, adding basketball in 1927. Sportswriters called him “Iron Man.”

When his body was through with sports, like many former athletes of the time, Thorpe headed out to Hollywood. As an extra and a bit player he appeared in at least 70 movies from 1931 to 1950. The total may be double that. Records for many of the so-called Poverty Row western serials Thorpe appeared in are lost.

While playing grossly stereotypical Indians, as the most famous among them he became a point man for the large diaspora of American Indians coming west to find work in the movies. He formed a casting company to pressure the studios to hire real Indians to play Indians, rather than anybody vaguely ethnic-looking.

Twenty-two years after he’d played any sport, Thorpe was named in 1950 by a poll of Associated Press sportswriters and radio sportscasters as the greatest male athlete of the half-century. The memory of 1912, Carlisle, and Canton was as fresh as yesterday in that pre-television era. Echoing his Olympic spread, Babe Ruth came in a distant second; DiMaggio didn’t even place.

Thorpe died three years later but the hunger to right his Olympic wrong only grew. By 1982 the Olympic ideal of amateurism was as good as dead. After years of pressure from the Thorpe family and passionate advocates such as Robert Wheeler and Flo Ridlon, the International Olympic Committee reinstated Thorpe.

Sort of. Duplicate medals from the original mold were presented to his family in 1983. But he was re-listed by the IOC only as a "champion," sharing the gold-medal status with the original silver medal winners who had been promoted in 1913 when Thorpe’s records were erased. The co-champion designation for these multi-sport events was an absurdity that Sports Illustrated called at the time "in the worst tradition of asterisk record keeping."

Even worse, however, Thorpe's records for each of the 15 events, as well as his point totals were specifically not reinstated by the IOC—and never have been. They remain the only official-but-not-official proof of what a remarkable athlete he was.

In this, his Olympic centennial year, Jim Thorpe is the ultimate Phantom Contender, there but not there.

But even that’s not all. After a bizarre four-year sequence of temporary storage locations (Los Angeles; Shawnee, Oklahoma; Tulsa), Thorpe’s body was finally buried in what is now known as Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania in 1957. In exchange for the body, the two tiny towns of Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk—Thorpe had never been in either—had agreed in a deal with his widow to consolidate and take his name. There were grand promises of a hospital for athletes, the Pro Football Hall of Fame, a Jim Thorpe sporting goods factory.

None of them materialized. Television took over to shape our memories of sports and the athletes who played them. None of Thorpe’s teams, or his school, survived intact as a popular franchise or institution with a vested interest in keeping his image and feats fresh to new generations.

Fast forward to 2010, when Thorpe’s youngest son, Jack, filed a federal lawsuit to have his father’s remains returned to Oklahoma under the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Times and sensibilities had changed. A legal contract for a human body in 1953 now looked unseemly at best. His sons felt that their father had never been properly laid to rest where he began and where he belonged.

The town decided to fight, insisting it had faithfully honored its side of the strange bargain. After Jack’s death in 2011, the Sac and Fox Nation and the last surviving Thorpe children, Richard and William, added their names to the lawsuit. If they win, the plan is to have Thorpe buried on what remains of the Sac and Fox reservation near where he was born in 1887.

As of this writing, the case is pending. Will there be a happy ending for Jim Thorpe at last?

Then the real reinstatement of Thorpe’s remarkable life in our collective memory can begin.