Greg Smith became Goldman Sachs’s most famous vice-president (there are around 13,000 at the firm) when he published an op-ed in The New York Times in March titled “Why I Am Leaving Goldman Sachs.” The op-ed, which detailed his disillusionment with the firm and what he saw as a shift from a client-centered culture to one myopically focused on short-term profits at the expense of clients, became a sensation and helped Smith ink a book deal worth a reported $1.5 million.

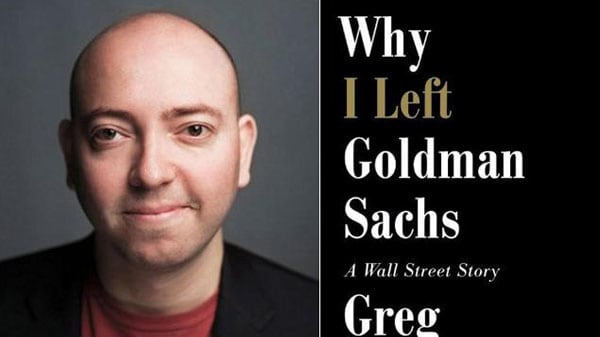

The book, called Why I Left Goldman Sachs: A Wall Street Story, is out Monday but copies have already leaked. Goldman Sachs, famous for its reticent stance toward the media, has gone on a full-court press raising questions about Smith’s account and has distributed talking points to employees on Smith’s book.

Here’s our look at the biggest claims in Smith’s tell-all memoir, and whether they stand up to scrutiny.

1. Goldman Sachs’s summer internship program is a lot like rushing a fraternity. Smith’s book opens with his 10-week summer internship at Goldman. It’s the summer of 2000. Smith, the 21-year-old South African immigrant studying at Stanford, is in the firm’s Open Meeting, a biweekly “form of boot camp for the seventy-five interns in the sales and trading program and a venerable tradition at the firm.”

According to Smith, about 40 percent of the summer interns got job offers for the following year after they graduated and one third of the evaluation was based on their performance at the meeting, where they are called on at random and drilled on “the firm’s storied culture, its history, [and the] stock markets.” The meetings start at exactly 6:00 p.m. and interns who are just a few minutes late have to go to a make-up meeting the next morning at 5.

One intern who couldn’t handle questions about Microsoft stock runs out of the room crying. (Another former intern disputes Smith’s account and told The New York Times that “No one ever ran out of a room crying.”)

Smith also writes that interns, who weren’t authorized to trade stocks or even talk to clients, were often tasked with making photocopies and ordering food for the traders and salesmen. A few years into Smith’s time at the firm, managing directors ordered an intern to get him a cheddar cheese sandwich, but “the kid came back with a cheddar cheese salad” (emphasis in original), the senior employee “opened the container, looked at the salad, looked up at the kid, closed the container, and threw it in the trash.”

2. Greg Smith loves Ping Pong. Smith was a scholarship student at Stanford who got a coveted Goldman Sachs internship and job offer. But he was also an internationally competitive Ping Pong player. He describes himself as a “table tennis phenom,” who represented South Africa in the 1993 Maccabiah Games as their No. 1 singles player.

During an annual Ping Pong tournament that Goldman’s Boston office hosted for its clients, Smith makes it to the finals where he faces a portfolio manager who was not “in the same league” as Smith. A VP in the Boston office, Ted Simpson, tells Smith that “this guy is one of our biggest clients” and that “we need to make this a close game.” After throwing the first game to the client, 21 to 17, Smith is up 15 to 12 when “Simpson … gave a little shake of the head, and then … gave a quick thumbs-down.” The portfolio manager ends up winning 2-0.

Smith’s farewell party before he leaves Goldman’s New York office for London is held at SpiN, “a subterranean table tennis club.” As Smith puts it “The party was loud and long and fun. A lot of alcohol was consumed, and a lot of table tennis was played.”

3. Smith was in a hot tub with a topless woman and felt weird about it.“I was in a hot tub in Vegas with three Goldman VPs, a managing director, a pre-IPO partner, and a topless woman.”

Smith’s best story of debauchery in the boom years is an account of a coworker’s bachelor party in Vegas in April 2006. At first, Smith feels uneasy about going in the first place—“the invitation gave me pause … when Goldman heavy hitters go to Vegas, the price point is very different from going with your college buddies.” When he gets to Sin City, he acknowledges that he “may have been overthinking it”; but a managing director is buying and eventually gives him $1,000 worth of chips, saying “That’s what it’s like … Enjoy the weekend.”

The next afternoon, Smith is in the hot tub, “sipping an ice-cold Red Stripe” with his brain “buzzing … with social/corporate/ethical discomfort.” He describes the woman as “unnaturally buoyant” and worries “how would that affect my prospects at Goldman.” Later, a Goldman partner who joined Smith in the hot tub sees him in the company bathroom and tells Smith: “That was a fun time this weekend.”

4. Smith’s time at Goldman also featured male nudity as well. According to Bloomberg, “[Goldman CEO Lloyd] Blankfein … had no idea who Smith was or why he decided to go public with his resignation.” Smith, on the other hand, knew Blankfein far more closely than he wanted to. Smith recounts seeing both Blankfein and his predecessor, Hank Paulson, at the Goldman Sachs gym. Smith describes Paulson as “a teetotaler—and a bird-watcher, ardent environmentalist, and exercise fanatic” who “put up some pretty impressive weight on the incline chest-press machine.” His encounter with Blankfein is more personal: Smith sees the CEO “walking around the changing room au naturel to dry off from his shower.” Smith is not taken aback and concludes that Blankfein’s nude strolling is not “a show of power” but instead just a practice “not uncommon among a generation slightly older than mine.”

5. Goldman played hardball with clients during the financial crisis. With major banks teetering and investment banks collapsing, Goldman needed a long-term, stable source of funding when the financial crisis hit its high point in 2008. So, Goldman would borrow money from big, cash-rich asset managers, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds for a year. In exchange for the cash, Goldman would pay its lender the returns of a “benchmark” index like the S&P 500 along with an extra 1 or 2 percent on top. The only risk for the lenders was that, if Goldman followed Lehman Brothers into bankruptcy, they might get nothing back.

Smith was tasked with reassuring his clients that Goldman would be around in a year and could pay them back. Smith has no doubts that Goldman will make good on its obligations. But he was concerned when Goldman was stricter than other banks about letting clients break the deal. Smith writes that “there are clients across Europe, the U.S., and Asia who hold a grudge against the firm because of its behavior then.”

6. Goldman employees called naïve clients “muppets.” The most memorable accusation in Smith’s original op-ed was that Goldmanites would refer to their easily manipulated clients as “muppets.” Smith writes that one junior employee told him “My muppet client didn’t put me in comp on the trade we just printed. We made an extra $1.5 million off of him.” The client had not checked the price for the trade Goldman quoted him with other banks or brokers and so Goldman got away with charging him more. During his time at Goldman, “muppet” turns from “a word that … evoked childhood memories of cute puppets” into the most salient indication that Goldman’s approach to clients had turned from helpful and advisory to hostile and dishonest.

(A Goldman investigation, reported in the Financial Times, found 4,000 references to “muppets” in internal emails, but that 99 percent of them were about the most recent Muppets movie.)

7. With The European financial system in crisis, Goldman was moving back and forth on the health of European banks.

Smith, who didn’t work on European bank stocks or derivatives, writes that Goldman was officially changing its mind on the health of European banks, “far too [frequently] to make any real sense.” Instead of making real evaluations about how European bank stocks would do, Smith argues that Goldman was advising clients to buy or sell the securities based on the needs of Goldman’s traders.

“We must have changed our view on each of these institutions from positive to negative back to positive ten times,” he writes, describing the bahavior of the firm’s London office as “obviously misleading and disingenuous.” Goldman officials told The New York Times that Goldman “never acted as a principal on any of those trades,” meaning that Goldman was doing these trades on bank options at the request of clients. Smith also doesn’t say specifically which banks Goldman was being inconsistent on or any particular trade that reflected a dishonest assessment of a particular bank’s health. Also, during 2011, the prospects for many European banks were fluctuating wildly—the European Central Bank announced a gigantic series of loans aimed at shoring up banks’ balance sheets and increasing their lending in December 2011.

8. Smith was disillusioned with his own compensation and position in the firm. Smith writes that he had “built the business 35 percent in my first year in London, had fixed a decade-long legal hurdle, and had increased the numbers of clients who he traded actively with by 80 percent. I had been praised in my year-end reviews.” He also writes that he had “outperformed my peers by 10 percent on my bonus,” but that he would have liked to have been promoted.

Documents acquired by Bloomberg, however, show that “he placed in the bottom half of the firm in regular evaluations from 2007” and that Smith had been denied a request for a promotion in January of 2012, he left the firm in March. Smith had requested $1 million in compensation in December 2011, roughly double what he was making before he left the firm.

9. The New York Times, before publishing Smith’s op-ed, had to make sure he was legit. At first, Smith submitted his op-ed to a general Times email address, oped@nytimes.com. After he emailed individual opinion editors, they dispatched one of their business reporters based in London, Landon Thomas, Jr., “to make sure I was exactly who I was purporting to be.” Smith met Thomas in the lobby of Goldman’s London offices, and Thomas conducted his vetting at a Starbucks, but not “the closest Starbucks to Goldman.” The conversation was entirely off the record. He told Thomas that he is not disgruntled or about to be fired, but that he “would like to have been promoted.” Thomas asked him at the end of their conversation: “How are you feeling about this? This is really going to happen.”

The takeaway? What’s new in Smith’s book isn’t particularly damning. And what’s damning—a rehash of Goldman’s SEC case over selling a mortgage security designed with the input of a hedge fund manager who was betting against it—has been discussed at length elsewhere. Now that Smith’s performance reviews and salary demands are public, the bank has raised serious questions about why Smith left Goldman in the first place.