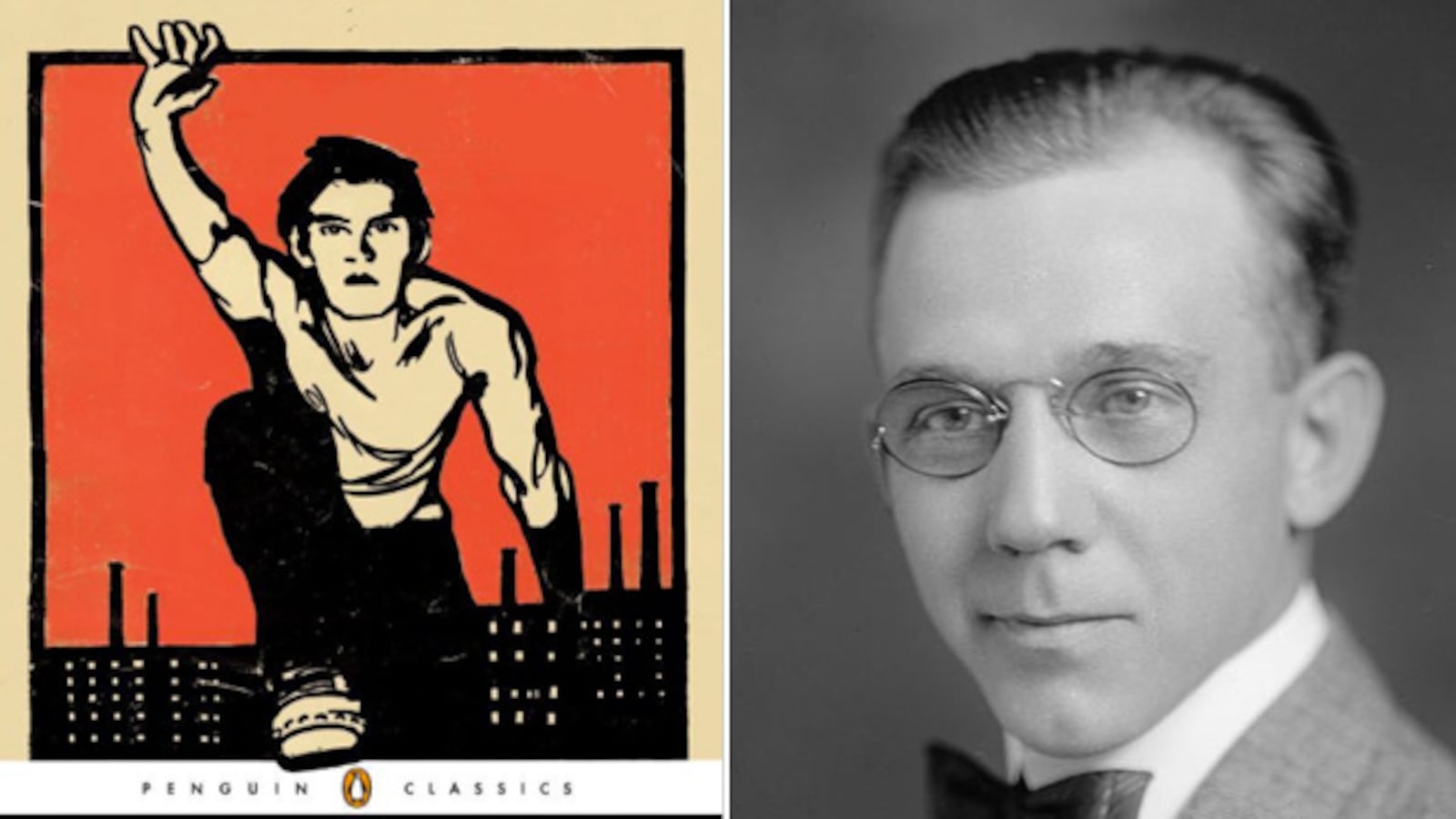

Ernest Poole’s His Family, about a middle-class New York widower and his three daughters in the 1910s, won the first Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1918. But it was Poole’s first novel, The Harbor—about a young man's collectivist awakening to the truth of American capitalism—that made a lasting impression, though it represented a more controversial pick for awards. Fine luck for the Pulitzer committee that it didn’t exist in 1915, when The Harbor came out, so it didn’t need to make that choice. The book spoke so powerfully at the time that many suspected that accolades given to His Family were vicariously intended for The Harbor. Few things speak more to America's deep ambivalence toward the working class than a "socialist masterpiece" being privately admired but publicly overlooked. Look around you today, at the debate over America’s healthcare and the paranoia over socialism, and it’s easy to think of The Harbor as a book that Fox News might not want you to read.

The Harbor, which was reprinted by Penguin Classics this year, is about a boy named Billy who grows up in an upper-middle-class family, in a home with a view over the New York harbor. His father is a pragmatic businessman. His mother is a woman of refined aesthetic, a lover of music and literature. She fears Billy is too enamored with the harbor's exotic cargo, foreign languages and gangs of urchins. She wants him to pursue a life of the mind.

And so he does. In college, his fascination with the harbor is purged from his sensibility to pave the way toward a respectable life of bourgeois entitlement. He knocks about with the gentleman caste, spends over a year in Paris emulating the heroes of the French literary canon, and returns home after his mother's death to find his father in bad health and his business in tatters.

To support his sister and ailing father, Billy takes up work writing puff pieces that glorify and rationalize the success of the rich and powerful. These men worship at the altar of efficiency and believe that any social injustice can be solved—sure, thousands of men die every year laboring for pennies on the harbor, but that will be addressed in good time with sufficient innovation and technology. Yet even as Billy becomes a literary sensation, his old college rival, Joe Kramer, continues to haunt him.

Kramer and Billy are kindred spirits, but Kramer accuses Billy of being blinded by the seductions of capitalism. While Billy was in Paris, Kramer was a reporter covering the peasant uprising in Czarist Russia and the Colorado massacre in which the National Guard and mercenaries killed striking coal miners along with their wives and children. He can't write about anything other than the depravities of the proletariat, and eventually makes a pariah of himself among editors who are interested in selling newspapers and appealing to advertisers. So Kramer casts his lot with the American untouchables of the Industrial Age.

These are the stokers, men who shovel coal into the furnaces of ships. They provide the emotional peak of The Harbor, and facilitate Billy's long-gestating political conversion. When they meet again, Kramer is a union agitator preparing for a massive general strike that will be the story's dramatic apex. He needs Billy to write about the movement's leader. So he shows him where he spent two years, where men are not men but "what the factories and mills and all the rest of this lovely modern industrial world throw out as no more wanted. So they drift down here and take a job that nobody else will take, it's so rotten, and here they have one week of hell and another week's good drunk."

Billy can't believe his eyes. "Again it came over me in a flash, the years [Kramer] had spent in holes like this, in this hideous, rotten world of his, while I had lived joyously in mine." Above deck, Billy finds himself "among gay throngs of people. Dainty women brushed me by. I felt the softness of their furs, I breathed the fragrant scent of them ... I saw their fresh immaculate clothes." Such are the contradictions of capitalism—it has spread unprecedented prosperity, yet some people pay the price.

The Harbor marked the heyday of the Progressive Era, when the unregulated greed of the Gilded Age gave way to a period of social activism and political reform that brought us unions and women’s suffrage. We are now in the wake of another Gilded Age, and the divide between capital and labor has rarely been clearer. We’ve yet to see the flowering of another Progressive Era, but perhaps that makes this the perfect moment to rescue The Harbor from oblivion.