In mounting its summer blockbuster, Picasso in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (on view through August 1), the Metropolitan Museum of Art is quick to admit that it was late to the party. Despite the Spaniard’s wide acclaim and ever-mounting between-the-wars success, the museum didn’t acquire its first Picasso until 1946—35 years after he first showed in New York City and more than 15 years after a then-spanking-new MoMA had begun building its bigger (and better) Picasso trove.

Click Image to View Our Gallery of Picasso in the Metropolitan Museum

So, why Picasso? Why now? ‘Tis the season, at least in New York—the uptown branch of Marlborough Gallery is hosting an excellent show of the artist’s strange, elegant, lanky, and grotesque prints of women, and the Martin Scorsese-produced, Arne Glimcher-directed documentary Picasso and Braque Go To the Movies is slated for a limited release on May 28. But the Met’s show is notable for several reasons. First, it’s the latest in a string of collection-themed exhibitions from newly cash-strapped museums ( Elles@Pompidou and MoMA’s Monet among them). It also shows what happens when institutions wait too long to get in on the action—and I mean that in a good way.

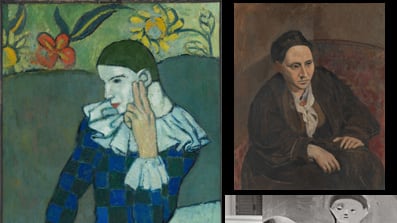

The Met’s exhibit features some 300 of the museum’s 500 works. Indeed, for every Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) there’s a lesser known, lesser polished, yet totally enlightening Seated Harlequin (1901) or La Coiffure (1906). And while the Met certainly has its hits ( The Actor—which was accidentally torn earlier this year—and that austere 1905–1906 portrait of Gertrude Stein) it’s the stranger items that really shine—the experiments, the erotica, the studies, the paintings and prints typically relegated to off-site storage, the sort of works that become available once all the masterpieces have been snatched up. It’s art that has rarely shown and, perhaps, most capable of offering yet another dimension to an already oversaturated field.

My main problem with the installation here is that the Met tried to shape its holdings into a proper retrospective instead of really delving into the specific themes and techniques seen in these less popular and largely unknown works (not to mention its own somewhat embarrassing history of collecting/not collecting Picasso). Instead, we get predictable gallery delineations (Blue Period, Rose Period, Cubism) and surface-skimming biographical details. But that’s not to say that the work itself isn’t remarkable.

The show opens with some of the artist’s commercial endeavors—posters of wobbly can-can girls in raunchy Parisian bars, very much à la Lautrec. Café regulars get a wispy treatment in air-light pastel and the artist’s harlequin fixation begins to emerge with a dense, almost caricature-like canvas from 1901. Moving into the “Blue” we see rare mother-daughter scenes (inspired, in part, by the artist’s visit to the Parisian Saint-Lazare prison/hospital for prostitutes with VD, and their offspring). There are ink drawings (tiny silhouette-like portraits of artists, poets, and friends) and the remarkable, touching, and über-blue The Blind Man’s Meal from 1903.

There was one major oddity in this gallery—a painting so shameful that Picasso himself denied having ever painted it (research has proven otherwise). La Douleur (1902–1903) depicts what is presumed to be a young Pablo, pants-less, hands clasped behind his head with a gaunt, very blue, raven-haired naked woman servicing him orally. The notorious lothario tried to play it off as a practical joke carried out by several artist friends—we’re not exactly buying it.

The next gallery offers rose-tinted portraits and a marked, pre-Cubism dalliance with neoclassicism. Here we see The Actor, fresh off the operating table and safely ensconced in glass, and La Coiffure (1906), a hazy domestic gathering of thick, wavy-haired figures meant to echo Old Master depictions of the Holy Family.

The Met’s Cubist holdings (sketches and studies, for the most part) pair nicely with these more neoclassical works, which are reflected, albeit abstractly, in sunken almond-shaped eyes, angular features, and networks of curves that feel derived from smoothly chiseled marble. Guernica-esque sketches I’ve only ever seen at Madrid’s Reina Sofía (permanent home to Picasso’s anti-war masterpiece) fill the room next door like tear sheets from a highbrow graphic novel, as does a painting of a dying bull and a stunning, exceedingly complex line drawing of the painter’s longtime love, artist Dora Maar.

There’s heavy emphasis, toward the end, on prints (mostly because someone bequeathed loads of them to the museum in 1979). But there’s more meat here than I expected. Created after Picasso’s 1958 relocation to the south of France, we see the artist looking both forward and back, updating Renaissance masterpieces, cave drawings, and other long-retired tropes while still playing with abstraction, a reductive sort of portraiture, color, shape, and line. It sets the stage perfectly for the late paintings that follow—which are certainly the least appealing of the bunch. Standing Nude and Seated Musketeer (1968) is just about as offbeat as it gets: absurd clashing palette, barely discernable subjects, flat perspective, lazy brushstrokes. But it, along with the museum’s other significant postwar Picassos, is nonetheless part of the more general narrative. And, as scholarship on these later works continues to expand (thanks in large part to art historian/expert-in-all-things-Picasso John Richardson), the one area where the Met might have a substantial leg up in the Picasso game.

Plus: Check out Art Beast, for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Rachel Wolff is a New York-based writer and editor who has covered art for New York, ARTnews, and Manhattan.