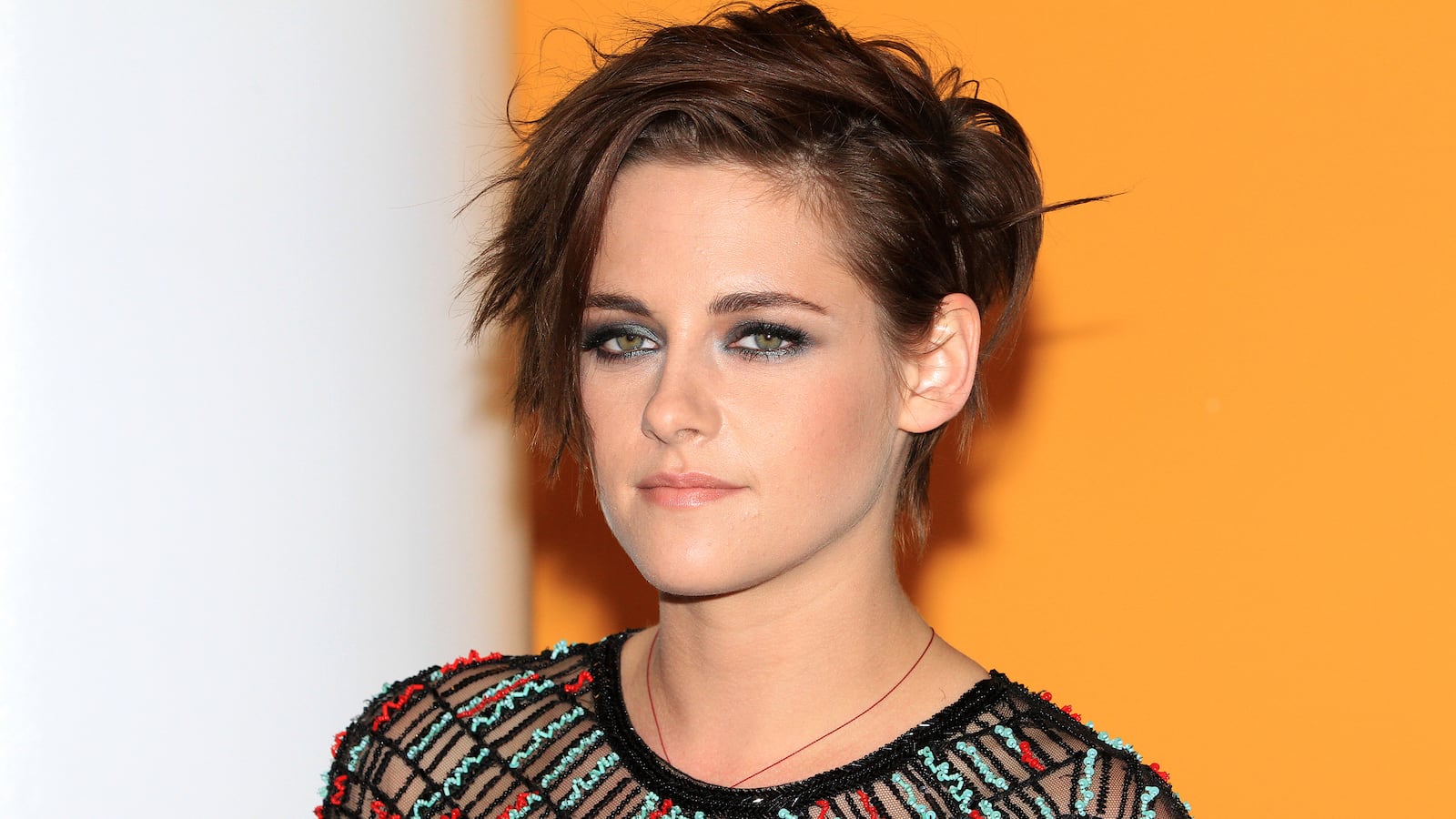

Kristen Stewart looks like a new woman. Yes, it’s an odd thing to say about a 24-year-old, but the steely-eyed Angeleno isn’t your typical twenty-something. At age 11, she tackled a pivotal seizure sequence for David Fincher in Panic Room with such ferocity that she burst several blood vessels in her eyes. “She reminded me of a young Jodie Foster,” said Fincher. She’s been forged in the crucible of Hollywood, enduring a polarizing film franchise (Twilight), tabloid controversy, and incessant scrutiny—and emerged all the wiser.

These days, she’s decidedly more Joan Jett than Bella Swan.

Stewart’s just emerged from her slumber and met me at the lobby lounge of the Greenwich Hotel, a hipper-than-thou hotel in Downtown New York, looking effortlessly striking in a baggy white T—exposing a right forearm tattoo of the illuminated eye in Picasso’s Guernica—black jeans, and short, dark hair. She got the bit of body art after wrapping Clouds of Sils Maria, a Swiss-set surrealist flick helmed by French master Olivier Assayas and also starring Juliette Binoche. It’s one of three indie films that’s earned Stewart heavy acclaim on the festival circuit, along with her gripping turn as a daughter struggling to cope with her mother’s (Julianne Moore) deterioration from Alzheimer’s in Still Alice, for which she’ll receive a “major Oscar push” from distributor Sony Pictures Classics, and last but not least, as PFC Amy Cole, a green guard at Guantánamo in Camp X-Ray, in theaters Oct. 17.

In Camp X-Ray, her guard is initially happy to serve her country in the wake of 9/11, but after observing the treatment of the prisoners there, and striking up an unlikely friendship with one of the detainees (Peyman Maadi, A Separation), she begins to have a change of heart.

After ordering coffee, we discuss her resurgence.

Camp X-Ray was shot on a shoestring budget of $1 million, but it looks much bigger than that.

It’s weird to say that the scope of it is pretty small considering what you see, but if you think about it, we had essentially three locations and shot it in 20 days. The key to the budget is it was so fast and we just gunned it.

It had been two years since you shot your last film, Snow White and the Huntsman. Were you being extra picky in the wake of Twilight because you knew you were under the microscope?

I’m never really that precious about choosing projects that don’t have every sure element that is a guaranteed good experience and/or success. There’s a lot of risk involved in this job, and it doesn’t bother me. This could’ve been a terrible movie! It could’ve been awful. It’s with a first-time director. But I still would’ve gotten what I got out of it had the movie not turned out as well as it did.

You tend to take those leaps. I remember Leonardo DiCaprio once saying that he has a policy of never working with first-time directors.

It’s smart. I’ve had experiences that have made me go, “Ugh, I have to be careful and make sure that every part is sturdy and that I won’t be let down.” If I was a director, I would be extremely conscious of my filmography. It says so much about the difference between putting your name on something and owning it instead of being one tiny part of it. Actors get to work all the time. If I make a bad movie every once in a while, I don’t care. I didn’t work after Snow White for about two years, but it’s because a lot of these projects didn’t come together. I’m decisive, but I’m definitely not a planner.

I have these talks with friends, and I’ll say, “Kristen Stewart’s a good actress,” and they disagree. Then I ask them what films they’ve seen of yours, and they just say, “The Twilight movies.” So, they haven’t seen, say, Panic Room, Speak, Into the Wild, Adventureland, etc. Do you feel like that series has unfairly colored people’s opinions of your acting ability?

Honestly, I don’t care. It’s fine. I’m really happy doing what I’m doing. I’m sure there are a ton of people out there who would hate my movies even if they saw all those, just as I’m sure there are people out there who are obsessed with Twilight and say, “I watched the series, and she completely let me down, and then I watched every one of her other movies, and I fuckin’ hate her!” And that’s cool! Just don’t watch my movies.

With Camp X-Ray, this is pretty heavy subject matter here in Gitmo. President Obama promised to close the place down in 2009, but hasn’t done so yet. Was part of the attraction to the project shining a light in this bizarre blight on America?

I was forced to really investigate. I knew that Obama wanted to close it down, and I knew that everyone else wanted to, too. Most people you talk to in America have kind of put it out of their minds. I didn’t jump on this movie to make a huge political statement, but it’s such an interesting story within an interesting context, and it’s more of a poke on the shoulder to remind you that this thing is here.

Your character’s relationship with Peyman’s detainee reminds us of the humanity of these people. We tend to view suspected terrorists as this nameless, faceless “other,” when they’re human beings, too.

As Americans, we should absolutely aspire to more than that. If you label something “bad,” people will justify the most terrible things. Just because you’re following a greater whole, suddenly you take the individual out of it and no one bears responsibility for anything.

The film doesn’t show any of the more controversial practices at Gitmo—like waterboarding, sleep deprivation, force-feeding, etc. It alludes to it. But if we showed all that stuff, people would instantly demonize the film. You see something like that and it becomes so polarizing. Yes, it was cool to be in a Gitmo movie, it was cool to play a soldier, and it was cool remind people that this still exists, but I also thought it was cool to play a simple, American girl who wanted to find her line and aspire to something bigger than her—only to find that things aren’t so simple. Most people in every state think, “Well, of course it’s a great thing to sign up for the Army,” and there’s no question asked beyond that—ever.

She really gets swept up in all the post 9/11 patriotism and signs up for Gitmo duty, only to find that it isn’t what she thought at all.

She’s simple, not very smart, and really socially inadequate—but a good person. So, if you can sign up, put a uniform on, and erase yourself, you don’t have to consider yourself anymore. You can take the individual out of it and say, “Well, this dignifies me. I’m good because of this.” And when that doesn’t end up being true, you actually have to contend with who you are. All she wants is to think, “They did 9/11, they’re bad, fuck that, I’m going to do my job and I’m going to do it well.” But then she gets down there and just can’t accept it; she can’t conform to that.

Right. The mistake we make is not viewing these detainees down there as people, too. We’re all people.

That is essentially so fucking evil, it’s crazy. It’s a ridiculous idea for you to think that you know anything for sure in life—other than to take care of your fellow people. Where the fuck do you get off thinking otherwise? These two people couldn’t be from more different worlds and perspectives, and probably disagree fundamentally on most things, but there’s a through-line for all of us—and that’s what people forget, and that’s what makes people capable of doing terrible things to each other. What makes you different from any other person that walks the earth?

This is a pretty ripped-from-the-headlines film. What issues are you passionate about in the news?

I don’t want to talk about that shit at all. Trust me, I’m only asking for it. When it comes time to stand up and affect change, I’m not the type of person to shout from the rooftops. Just because you’re an actor and in the public eye, people think that’s how you must be. But there are other ways to do that. That’s not me.

When you talk about Camp X-Ray, Still Alice, and Clouds of Sils Maria, these are three films anchored by strong, flawed, complex women. These films tend to be a rarity in Hollywood, and usually come in smaller indie packages.

Me and Juliette [Binoche] were talking about it because this question does come up, and she said, “Oh, I don’t answer that question anymore. It’s so cliché.” And I said, “Well, it’s so cliché because it’s entirely true.” And she said, “Yes, maybe in Hollywood.” Because in France, due to the history of French directors having romantic relationships with their lead actresses, they tend to tell more female-centric stories. In America, there are way more male filmmakers than female ones, and they want to tell more masculine stories. Most of our great films that we’re proud of, you’ve got Bob De Niro, Jack Nicholson, and the bravado is overwhelming. And that’s still going on. I read a million scripts and people say I choose my scripts carefully, but it’s just so obvious when the role is different, and complex, and not some typical, archetypal girl, because they’re so rare. Not to sound cliché, but it’s a male-dominated and driven business.

“It’s A Man’s World,” to quote James Brown.

[Laughs] Yeah. But that’s OK, because it’s fun to be the underdog.

There just needs to be more female filmmakers.

Exactly! That’s it. I’ll do it.

A case study would be your Twilight director Catherine Hardwicke. This is a very accomplished filmmaker and, five years after directing that hit, her latest film basically went straight-to-video. That has to be indicative of a larger problem within the industry, that she was basically given one Red Riding Hood before her power was stripped away. A male director is given a lot more chances.

Yeah, that’s true. That’s a thing that women have to do—you must persevere. That’s what we’ve been doing. You need to make something that’s undeniably good. If a woman makes a bad movie, or does something stupid, then the door just slams shut. It’s fucked up.

A lot of young actresses these days are coming out against being labeled a feminist. It seems to be a generational thing, where people from the older generation see it for its definition—equality for men and women—while the younger generation for some reason views it as a more divisive term.

I know what you mean. That’s such a strange thing to say, isn’t it? Like, what do you mean? Do you not believe in equality for men and women? I think it’s a response to overly-aggressive types. There are a lot of women who feel persecuted and go on about it, and I sometimes am like, “Honestly, just relax, because now you’re going in the other direction.” Sometimes, the loudest voice in the room isn’t necessarily the one you should listen to. By our nature alone, think about what you’re saying and say it—but don’t scream in people’s faces, because then you’re discrediting us.Relating it to my one little avenue, people say, “If you want to make it in the film industry as a woman, you have to be a bitch.” No, you are going to ruin any chance you have and give us a bad name. It’s the overcompensation to where our generation goes, “Relax,” because it’s been easier for us, and because we don’t have as much of the anger, so it’s like we can’t get behind it and it’s a bit embarrassing. But that being said, it’s a really ridiculous thing to say you’re not a feminist.