Early Monday morning, the board of trustees at the Museum of Contemporary Art gathered at the museum in downtown Los Angeles to elect New York art dealer Jeffrey Deitch as the fourth director of the museum in its 30-year history. Absentee board members called into the room. The group discussed Deitch—one of a few finalists in a search that has spanned several months. “This is the first time that a gallerist has been the head of a museum, so that was controversial,” one trustee said. “It was discussed in great depth.”

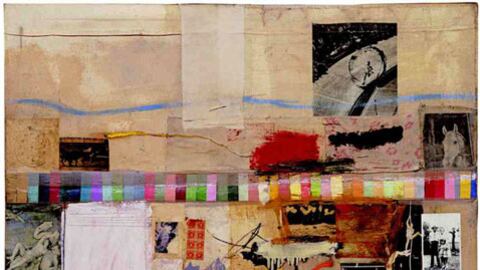

Click Image to View Our Gallery of MOCA’s 30th Anniversary Exhibit

But when the time came to vote, the board—led by the museum’s life trustee, philanthropist Eli Broad—unanimously elected Deitch. One board member described the mood as “joyful.” Another called it “exuberant.”

But around the art world, Deitch’s appointment has raised more questions than it answers. Deitch, 57, now helms a profitable New York gallery, Deitch Projects, which represents such artists as Vanessa Beecroft, Kehinde Wiley, Ryan McGinness, and Barry McGee. To avoid any potential conflicts of interest, the gallery will close by the time Deitch takes the position at MOCA on June 1, though the fate of his artists and staff members (many of whom enjoy stipends) is unknown. Deitch has said that before leaving the job, he will make sure all affected will have “a good transition.”

Much of the concern over Deitch’s selection (and the subject of much of its press) has been his potential pitfalls in transitioning from the commercial world to the nonprofit one. In many ways, these worries are unfounded: Deitch’s contract reportedly contains safeguards against conflicts as dictated by the American Association of Museums and the Association of Art Museum Directors. Deitch declined an interview for this story.

“He will not be doing anything for profit in the art world,” said board co-chair Maria Bell. “He is under a contractual obligation—and beyond that, a commitment to all of us. He wanted to make sure that we all know he would behave with utmost propriety. All of those things have been hammered out, and we’ve made provisions for all of this. The one thing that we don’t want is for anyone to wonder what’s going on here.”

But as the wall between commercial and nonprofit becomes increasingly porous, "conflict of interest" is harder to define. “There are ethical boundaries that need to be followed,” one major museum director said. “That said, the idea that these are two separate worlds is so patently false. Of course they’re interconnected in all kinds of ways. If you’re buying art, the market is something that you pay attention to. Whenever you organize a show, you’re worried about insurance values. You have to be keenly aware of what’s happening in the market.”

Deitch has no experience in the museum world. But with a Harvard MBA, and a career that includes founding Citibank’s art advisory program in 1979, Deitch has decades of business savvy. And, in carefully tailored suits and plastic-framed glasses, he certainly looks more Gordon Gekko than El Greco. “This is probably overly simplistic, but everyone’s talking about how well-dressed Deitch is, he has this image of kind of being a pimp,” said New York artist William Powhida, whose work consists mainly of satirical portraits of art world figures. “If I were in Miami, Deitch is the dealer I would want to go strip clubs with. I would want to go shopping on Rodeo Drive with him if we were in L.A.”

Regardless of whether he would make for a good companion at the club or at a bespoke tailor, one thing’s clear: Deitch is cool. Kanye West produced VB64, Vanessa Beecroft’s installation at Deitch’s Long Island gallery, and his show last summer, Black Acid Co-op, attracted crowds to an interactive meth lab by Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe (which reportedly cost Deitch $100,000, yet earned nothing).

Deitch’s shows have been unconventional—even un-commercial, in that they are arguably better suited for public consumption than private purchase. Deitch himself has categorized his role at the gallery as, “in a way running my own private institute of contemporary art.” He explains: “I’ve run a public gallery with three spaces and with lots of public projects. Ninety-nine percent of my constituency running my gallery is the art-public, same type of public as the public of MOCA.”

With a hip persona and acumen of fun, boundary-pushing shows—one of his last will be an exhibit by the actor James Franco—Deitch is also primed to resonate with Los Angeles’ younger art crowd. “He’s known for his relationship to youth culture and music,” said the museum director. “That’s something for which there should be a large audience that’s really been barely tapped by the institutions.”

But involving local young people and artists in the museum may be harder than it looks. As Deitch prepares his move across the country, there’s a mixture of both excitement and resentment to welcome him. On one hand, there’s hope that Deitch’s appointment will bring new attention to the museum. “I hope it attracts ripples of attention to the L.A. creative community,” says local art consultant Emma Gray. “We need a bit of an extra push over here. This market could be opened up—a lot of the creativity is out here. Everyone’s starting to pay attention to L.A., and [his appointment] is a further boost.”

As Deitch said in a statment, “MOCA has an extraordinary history, and it’s my goal to position MOCA as the most innovative and influential contemporary art museum in the world… I am excited by the opportunity to play a role in making MOCA and Los Angeles the leading contemporary art destination.” This struck a note with Diana Thater, a Los Angeles-based artist who is the founder of MOCAMobilization, an organization that rallied for the museum’s independence during its nadir of financial trouble. “MOCA already has that reputation,” she says. “To say that it needs to be put on the map shows a lack of knowledge for the museum. It’s a shame on his part that he doesn’t know who we already are.”

Deitch’s immediate task will be to fundraise for the museum, which is still recovering from a near-death experience financially. MOCA had already spent $38 million of its endowment when the financial meltdown occurred in 2008, which forced the board to seek emergency funds. It found support from Eli Broad, who offered a $30 million bailout. (Half of that pledge will be paid out in $3 million installments for the next five years.) The rest needs to be replaced. It is this—which, according to once source means Deitch must raise $60 million in four years—that will likely be his biggest challenge. But given the client base he has built up over the decades—David Geffen was a longtime buyer—many in Los Angeles are hopeful Deitch will attract new donors.

Another challenge for Deitch will be the size and moving parts of the museum. At the gallery, the buck stopped with him—but at MOCA, he’ll answer to the board of trustees. That will inevitably mean establishing a new relationship with Broad, a longtime client, who heavily supported him for the job. But there’s uneasy precedent there, as Broad similarly steered Michael Govan into the top spot at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2006, before Govan broke away. “At a certain point, the people who he had brought in were strong enough to say no to him,” the museum director said of LACMA. “Something like that has to happen at MOCA eventually.”

Plus: Check out Art Beast, for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Isabel Wilkinson is an assistant editor at The Daily Beast.