The shelves of America’s bookstores do not accurately represent the inner life of their customers. Where are the Tea Partiers dreaming of libertarian utopias? Whence the poets who howl for the rights of the unborn? The Mormon missionary comedies of manners? American literature seems to want for authors of a Republican slant.

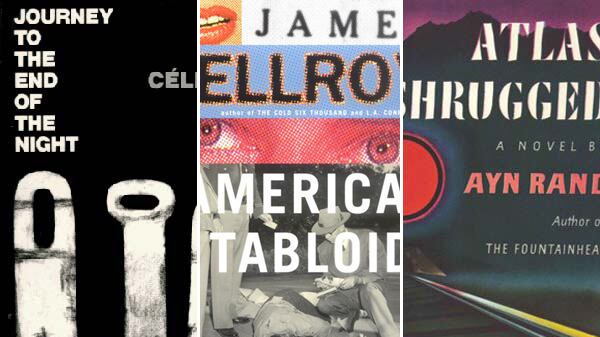

Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, published in 1957, is often the first overtly political text that a young right-winger picks up. The book presents a nightmare: socialists have taken over, and they keep anyone the least bit creative hamstrung with regulations. America is drooping into decrepitude, so the world’s most brilliant industrialists are going underground in protest. Plutocrat sweethearts Dagny Taggart and Hank Rearden join the movement as the masses clamor for revolution. Will the natural aristocracy assume its rightful place? The message is simple: the world is filled with jealous mediocrities. Be your selfish self and ignore them.

Rand’s sentiment is one that many, including America’s president, find adolescent. Barack Obama dismissed Paul Ryan’s professed affection for Rand, calling it “one of those things that a lot of us, when we were 17 or 18 and feeling misunderstood, we would pick up.” The consensus among scholars and writers is that Rand’s novel is too much of a vehicle for her ideas to be worthy of serious literary acclaim. But her quarrelsome ideology does have an appealing contrarian energy.

Republicans, of course, like to read and write as much as anyone else. But they seem to have a preference for journalism and not for fiction. In Tom Wolfe they found a champion of the former and not the latter, someone capable of showing the ridiculousness of the left. Perhaps Republicans who are drawn to the crisp arguments of an essayist like Paul Fussell might be lured by a novel with a rhetorical snap.

They might consider Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night, published in 1932. John Banville declared it “the finest novel ever written by a far-right sympathizer,” and he also wrote the foreword to its new edition. In the book, one Ferdinand Bardamu volunteers to go to war. But he isn’t much of a soldier, let alone a patriot, and he leaves horrified. His impression of the French colonial empire is no better, nor is he fond of Detroit, then a thriving center of industrial capitalism. (Remember those days?) He doesn’t like Paris. He doesn’t like being a doctor. Bardamu doesn’t like much of anything. Though there is nothing especially political about the book, reading it is like experiencing an allergic reaction to modernity. Journey to the End of the Night does not offer readers much more than nihilism as a response to a detestable world. It reads like the caffeinated grousing of a shell-shocked veteran whose ideas are bankrupt yet still has the power of style, the weapon of language and rhetoric. It is hard not be swept up in the intensity of Bardamu’s feelings.

There are plenty of stylish conservatives in the canon. Flannery O’Connor’s short story “The Lame Shall Enter First” uses the idea of an omniscient, judging God to justify intricate shifts of perspective and steep the atmosphere in religious dread. An atheist father invites a troubled teenager into his home to spite his grieving son, and he is punished for it. O’Connor doesn’t waggle Catholicism in her readers’ faces, but she does seem to say, “Believe what you want, but don’t say I never warned you.”

The belief in an immortal soul is important for both fictional suspense and conservative fear, as it is a hell of a thing to lose. James Ellroy, professed friend of policemen, Lutheran churchgoer, and serial supporter of the Republican Party, writes fiction that relies on a stark contrast between good and evil. His books are maniacally fast and innovative. He takes for granted that bad men die bleeding, and isolates a sliver of American history—Los Angeles after World War II—and fills it with sinners as lust-mad and doomed as Captain Ahab in Moby Dick. Freed from worrying about motive, Ellroy experiments with the way that he deploys information. American Tabloid is the beginning of an epic trilogy that imagines John F. Kennedy’s assassination from the perspective of his sleazy associates. The book delivers a torrent of detail, in a form as precisely machined as the innards of a Swiss watch.

Ellroy laces his later texts with newspaper clippings, some truncated to headlines, police reports and the transcripts of surreptitious surveillance. It’s a method that draws history with sweeping strokes, a technique pioneered by Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos, whose U.S.A. Trilogy is a distant but direct ancestor of Ellroy’s Underworld USA Trilogy. Republicans may enjoy Dos Passos, too, as they watch 12 characters careen through history, each of them eventually wanting to settle down.

These novelists trace the contours of what a Republican literary canon might look like. But there is one thing missing from this list: the writers themselves. With the exception of Ellroy, whose fiction is confined to a narrow moment in American history, the authors mentioned are all dead. The Republican Party is in a moment of crisis, and there is a difference between being conservative and being a member of today’s right wing. The right has been radicalized by a ridiculous ideology that would be outrageous if expressed in literature. By comparison the liberal left is in an elegiac mode and mourning for an America that used to at least try to include everyone. The Democrats are perhaps the true conservatives, the nostalgic ones. In the year 2012, Republican writers are not publishing much literary fiction of note, as the right has traded in sentimentality for fantasy, spirituality for fanaticism.

The Telegraph reports that Moby Dick is Barack Obama’s favorite novel. Mitt Romney, on the other hand, says he likes The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which is a children’s book, although it’s a far more politic choice than what he admitted to reading in 2007: L. Ron Hubbard’s Battlefield Earth. Paul Ryan, meanwhile, has remained steadfast in his adoration of Atlas Shrugged. George Orwell, writing about the frontiers of art and propaganda, suggested that literary dark ages have an important aesthetic purpose. They remind authors that when “one’s scheme of life is constantly menaced; in such circumstances detachment is impossible. You cannot take a purely aesthetic interest in a disease you are dying from; you cannot feel dispassionately about a man who is about to cut your throat.” Without being detached from one’s subject matter, art for art’s sake becomes impossible. Perhaps Republicans (and, increasingly, Democrats for that matter) don’t read serious literary fiction because they are so convinced that the values they champion are being stomped on by the plutocrats Rand plucked from society.

Republicans might summon their literature to defend them, as the stakes are so high—Obamacare socialism! Gay marriage apocalypse! But no one likes to spend eight hours being hectored by a political bore. Unless, of course, you happen to be a political bore yourself. In which case, it remains easy to find propagandized pap to fill your bookshelves with. May I suggest Atlas Shrugged?