On Nov. 7, 2020—the day television networks called the election for Joe Biden—then-President Donald Trump’s campaign manager was trying his best to break through to his deluded boss: The election was over.

Specifically, as Bill Stepien, the Trump campaign manager, later said in his testimony to the Jan. 6 Committee, Trump’s chances had dwindled since the election to the point where they were “very, very, very bleak.” The campaign hadn’t been able to verify any claims of voter fraud, and Stepien placed little hope in any “realistic legal challenges.”

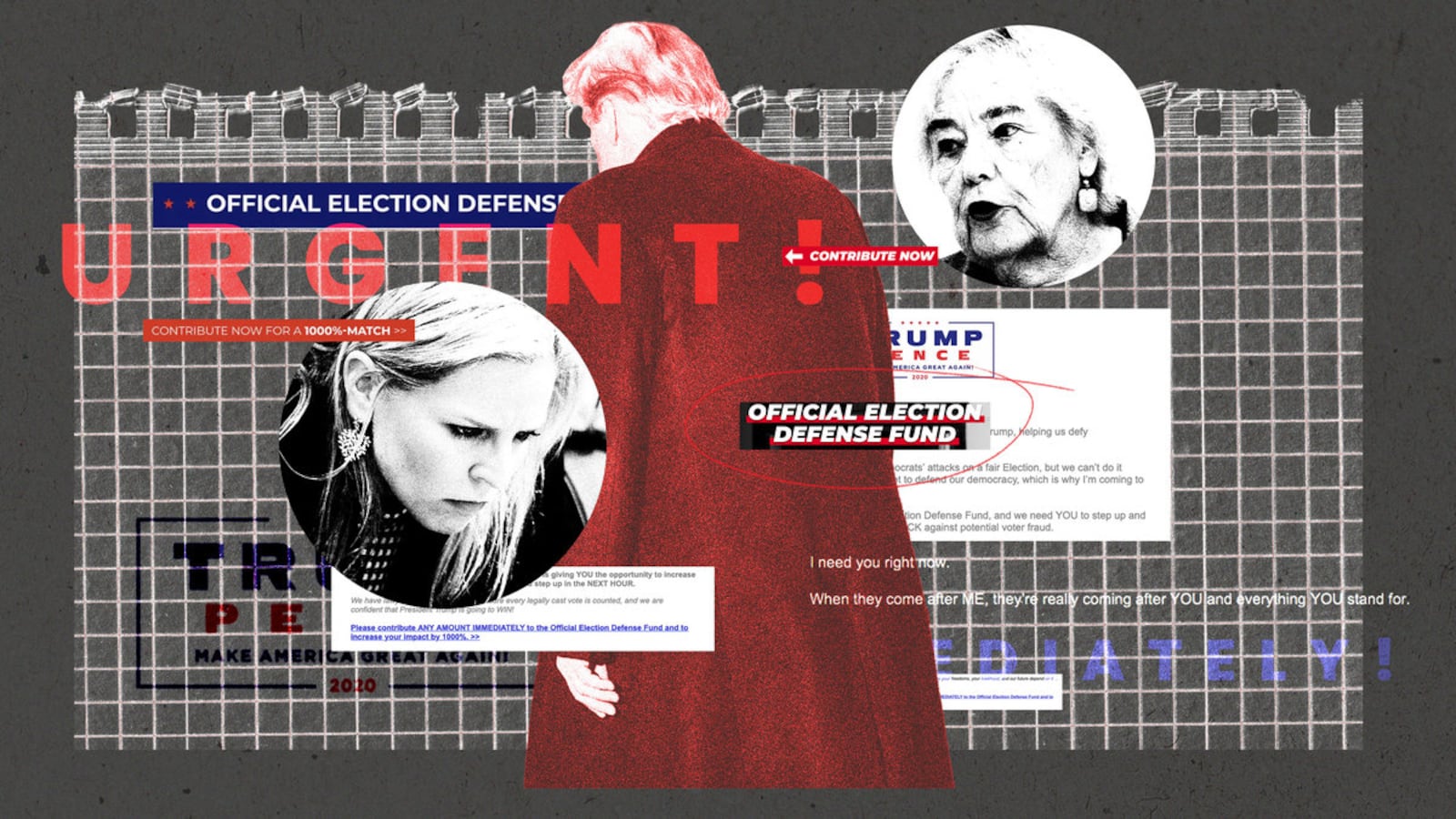

That same day, the Trump campaign sent a fundraising email claiming that “President Trump will easily WIN the Presidency of the United States with only legal votes cast.” The solicitation called on supporters to donate any dollar amount and join something called the “Election Defense Task Force.” The campaign, it said, was “counting on members to help [Trump] fight back and secure FOUR MORE YEARS.”

While the Jan. 6 hearings have delivered explosive testimony and evidence suggesting that a number of former administration officials may face criminal liability related to the attack on the Capitol—possibly all the way up to Trump—there’s another potential criminal liability that has largely been lost in the news.

That would be the sprawling wire fraud conspiracy which the Jan. 6 special select committee alleged in its second hearing, on June 13, a scheme which legal experts say contains the ingredients for possible federal charges against officials with the campaign and the Republican National Committee—as well as Trump himself.

The fundamentals of that case may have been lost under the hearing’s success—the instantly viral revelation that Trump had raised $250 million on the Big Lie, much of it for a legal fund that didn’t exist.

But the case they laid out that day is as simple as it is compelling:

- Campaign officials and lawyers eagerly testified that they had told Trump they didn’t believe the claims of fraud

- The campaign team then continued to blast out hundreds of emails raising money off claims that officials, by their own admission, knew to be false

On top of that, many of those emails told supporters that their money would go to a legal fund that didn’t exist.

Former U.S. attorney Barb McQuade, who teaches at the University of Michigan School of Law, called wire fraud prosecutions “bread and butter cases for federal prosecutors.”

“If it can be shown that Trump or others sent an email asking for money for one purpose, and then used it for another, that could constitute fraud, regardless of whether it can be proved that they knew the election had not been stolen,” she said.

Natalie Adams, a partner at Bradley LLP who prosecuted wire fraud cases as an assistant U.S. attorney for the Middle District of Florida, told The Daily Beast that “the committee’s definitely got something.”

“You don’t get to say things you know to be false,” Adams said, and the testimony of campaign officials copping to their true beliefs could trip the federal wire fraud statute.

“It’s not whether you know something absolutely for sure,” she explained. “It’s if it’s ‘reasonably foreseeable’ to you that people will believe promises and statements that you either know aren’t true, or are reckless or deceptive, which you are trying to use to get something of value.”

As far as what these top campaign officials knew at the time, they were not only quick to say they didn’t believe the claims of fraud, but told Trump repeatedly he had lost fair and square—while the campaign was sending the emails otherwise.

In one video, former top Trump adviser Jason Miller recalled that, not long after the election, the campaign’s head of data told Trump “in pretty blunt terms that he was going to lose.”

The campaign’s former general counsel, Matt Morgan, recalled that a group of advisers delivered the same message in the White House. “I think everyone’s assessment in the room, at least amongst the staff . . . was that [the alleged fraud] was not sufficient to be outcome-determinative,” Morgan said.

Another campaign lawyer, Alex Cannon—whom the campaign had specifically tasked with assessing election fraud—testified that he told Trump White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows in mid-to-late November that the campaign hadn’t found “anything sufficient to change the results in any of the key states.” Cannon also recounted telling another Trump aide, Peter Navarro, that the “election was secure,” citing a Homeland Security assessment Cannon had read.

The panel played clips of Stepien, the former campaign manager, describing his efforts to get Trump to see the writing on the wall.

“What was happening was not necessarily honest nor professional, and that sort of led to me stepping away” from the campaign, he said.

The committee also presented recorded testimony from the campaign’s then head of digital strategy, Gary Coby, admitting that the “Official Election Defense Fund” at the center of dozens of fundraising emails was a “marketing trick” and did not, in fact, exist.

Yet in this same period, the Trump campaign continued to barrage small-dollar donors with fundraising emails. They sent as many as 25 a day, most of them perpetuating the Big Lie.

For instance, on Nov. 7, the same day Stepien offered his “bleak” outlook, the campaign bombed supporters with 23 fundraising emails—from Trump, three of his adult children, the chair of the RNC, Vice President Mike Pence, and a number of vague “funds” that don’t appear associated with any real entity.

The emails claimed the campaign was “counting on members to help [Trump] fight back and secure FOUR MORE YEARS,” and that Democrats were “trying to mess with the results” and “rip a TRUMP-PENCE VICTORY away from you.” They all asked for money.

(A researcher archived these solicitations in real time and has made them available in an open document.)

In a Nov. 10 fundraising email, Trump claimed that—contrary to Stepien’s testimony—his early lead on election night had disappeared “miraculously.” A missive the next day bemoaned “voter fraud” and “interference” from “Big Media and Big Tech,” followed by a money request under the subject, “Proof of election fraud.”

On Nov. 13, Team Trump scaremongered a laundry list of (at best unsubstantiated, and at worst disproven) fraud allegations in Antrim County, Michigan. A week later it was “illegal activity in Wisconsin.”

The deception wasn’t just in the body of the emails, either. There were incorrect subject lines and eye-catching headers. Fourteen included the phrase “voter fraud.” Another 14 undermined confidence in ballots—“Mail-in ballot HOAX!” (Nov. 10) and “221,000 ballots were COMPROMISED” (Dec. 2)—with five targeting “illegal ballots” specifically. A dozen headers and subject lines played on defending “election integrity,” and 29 called on donors to “defend the election.”

This continued for weeks. The campaign even begged for alms on the morning of Jan. 6, citing “voting irregularities and potential fraud.”

But while the mendacity of those emails is clear, the blame is still somewhat foggy. Former U.S. attorney Joyce Vance said the committee is “telling us the story of what happened,” without the constraints that limit prosecutors.

“The biggest question I see with a wire fraud case, based on publicly available information, is, who are the defendants?” Vance wondered. Justice Department prosecutors would need to know who exactly designed, approved, and disseminated the solicitations before they consider whether the scheme constitutes wire fraud—“although it looks like one!”

The Jan. 6 committee has taken steps to figure that out. In February, the panel subpoenaed the RNC’s digital marketing vendor, Salesforce, for reams of internal data. The order would net information about email authors, project managers, and analytics such as open rates and targeting, all of which would help flesh out the scheme. The RNC is still fighting the subpoena in court.

A Trump representative did not reply to The Daily Beast’s emailed questions. In response to a detailed request for comment, RNC spokesperson Emma Vaughn provided a statement that attacked Democrats but did not address any of the allegations.

“This is nonsense—[House Speaker Nancy] Pelosi’s committee is partisan and illegitimate,” the statement said. “Americans want Congress to focus on the most pressing crises created by Biden and Democrats—record gas prices, the worst inflation in 40 years, empty shelves, and rising crime—not conduct a political circus in prime time.”

The committee, and possibly prosecutors, might start their search with the officials who had authority over email fundraising operations. That would include advisers quoted above—digital lead Gary Coby (his “unquestioned domain”), along with top strategist Jason Miller, and campaign manager Stepien, all of whom exercised direct oversight, according to a former senior campaign official.

Adams, the former AUSA in Florida, said prosecutors could build out a conspiracy to commit wire fraud—and that might reach Trump.

“With conspiracy, you don’t necessarily have to commit an overt act. And jury instructions don’t require proof of a formal agreement, because criminal actors avoid doing that,” Adams pointed out. “But if people work together and profit from it, it’s helpful to show who had the access and opportunity to review those communications, and who would be likely to know by virtue of their job what is ‘reasonably foreseeable’ to occur, who are charged with vetting the truth of statements, and so on.”

With Trump specifically, she said, it seems he was in a position where it would be “foreseeable that people around you will carry out your instructions and carry out your intent.” She also noted that as a fact-checker for a former president, she “triple-checked” every claim that went out.

The emails didn’t just have Trump’s signature line. They also came from his campaign team, other officials, and members of his family (though not Jared Kushner or Ivanka Trump).

Of course, that doesn’t necessarily mean those people actually wrote the letters, or even read them—though if they had not, that might also raise fraud concerns.

Several fundraising asks came from Donald Trump Jr., one of which said Democrats “lie and cheat,” and that “this fight is worth having.” Eric Trump once asked supporters to hand over cash to “help expose the fraud,” as did his wife, Lara.

Other public figures passed the fraud hat, too, including former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and Rudy Giuliani. Multiple emails came from then-Vice President Pence, one of them promising “we’ll uncover all Election fraud.” Some of the recipients of that email would later attend the Jan. 6 riot that targeted Pence and members of Congress for violence.

A Nov. 7 email attributed to RNC chair Ronna Romney McDaniel told donors that Trump had “activated the Official Election Defense Fund”—which, again, did not exist—adding that she was “confident that President Trump is going to win.”

Aside from Trump himself, “Team Trump 2020” made some of the most explicit allegations of fraud. “We are going to prove that President Trump won by a landslide and we are going to reclaim the United States of America for people who voted for freedom,” read a Nov. 21 request.

Two weeks later, Team Trump 2020 claimed they were “pacing BEHIND” their goal for the Election Defense Fund. The campaign had raised nearly $500 million, warning potential donors that “if we don’t do something quick, we risk losing America.”

It went on to tell donors their contribution could actually reverse the election results: “If every supporter took action and contributed TODAY, we’d be back on track and would have what it takes to SAVE AMERICA from Joe Biden and Kamala Harris.”