Many people dream of becoming spies. Life as James Bond or a character from an Alan Furst novel seems racy and well-paid. But when faced with actual espionage—the training, the danger, the use of other human beings for motives that can feel questionable or even sordid—they forget about it. They move on.

Juan Pujol didn’t move on. At the beginning of World War II, this brilliant young Spaniard wanted to “start a personal war with Hitler,” and espionage was his chosen method of doing it. He was willing to risk his life—and that of his gorgeous wife, Araceli—to have a great adventure and perhaps save the world in the process.

There were a few problems with this plan, though. Pujol wasn’t a spy. He was an ex-chicken farmer and hotel manager who was, in the spring of 1941, stuck in a one-star dump in Madrid. He had no training in espionage. He had no contacts in the espionage world. He was living in a Fascist-controlled country that was infiltrated by thousands of Nazi agents and informers. He had about as much chance of becoming a world-class intelligence operative as you or I have of winning the gold in the Olympic steeplechase.

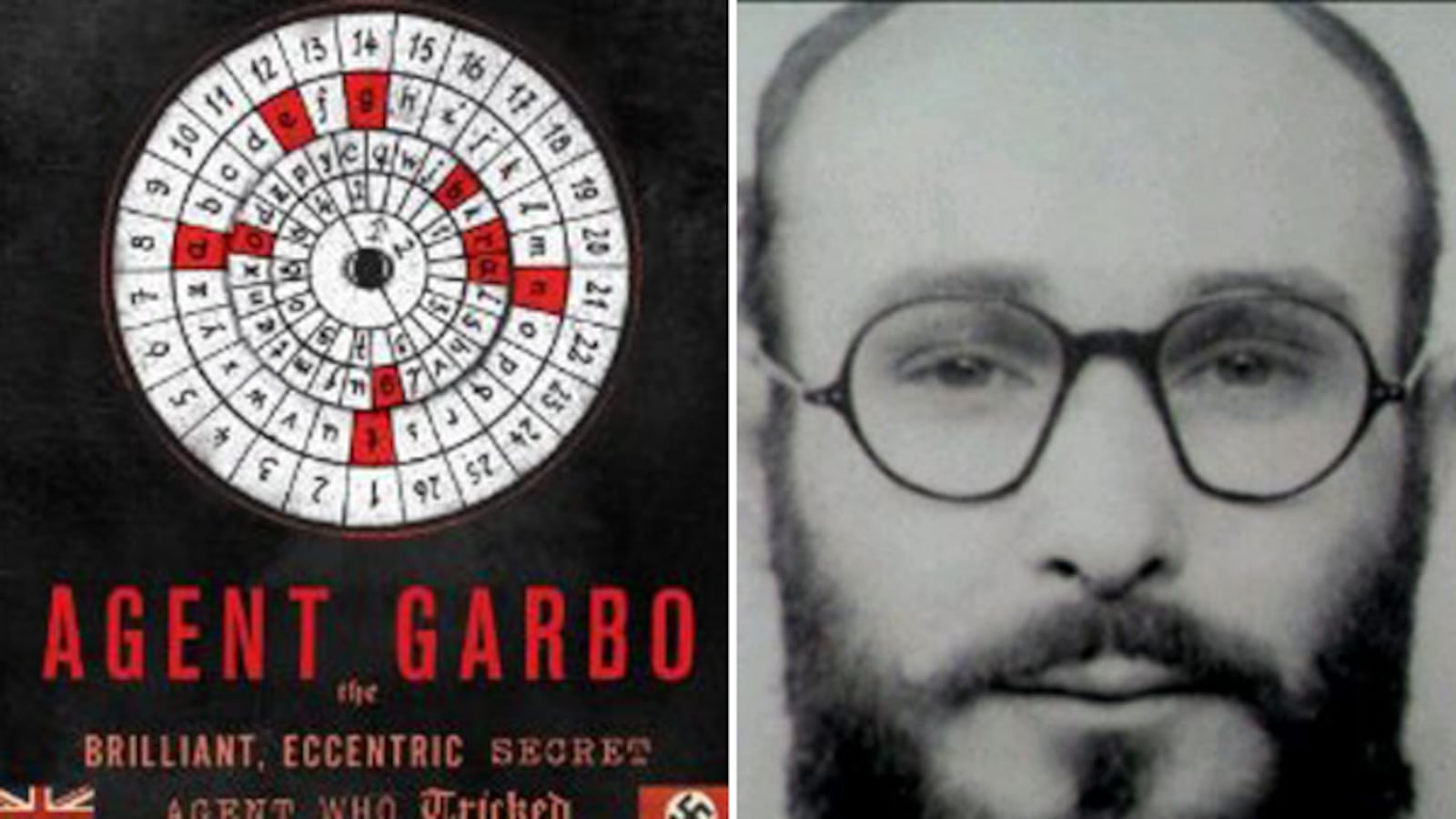

Only one year later, Pujol had transformed himself into something almost unprecedented in the long history of intelligence. He was on his way to becoming a completely self-made master spy. By that time, Pujol was a rising star in MI5’s stable of double agents. The Germans trusted him implicitly. He conducted missions that involved global assets and caused the Nazis to send fighter planes and destroyers to attack convoys that didn’t even exist. The Allies were so in awe of his powers of confabulation that they’d given him the code name “Garbo,” because he was the greatest actor they’d ever seen.

And when the Allies began planning D-Day, it was Pujol who was chosen to lead the deception effort. He would be the point of the spear in convincing Hitler that the Normandy landings, the greatest invasion in human history, was in fact a fake, and that a million-man army was about to attack him along another length of French coast. Pujol was going to be lead actor in the most complex wartime deception ever conceived.

This simply doesn’t happen. Nobodies don’t will themselves into the game in the course of one short year. But somehow this mischievous and enigmatic man had done just that. At a price, however.

At the beginning of his career, Pujol had only one thing to recommend himself as a spy: raw imagination. He’d been a dreamer since childhood, which he spent “covered in bandages” after acting out wild adventures as an explorer or the Hollywood cowboy Tom Mix. His parents didn’t understand him, didn’t understand why he crashed his tricycle through plate-glass windows and nearly decapitated himself while acting out some daydream. Pujol tried to explain that his imagination “controlled” his brain, and that he was powerless to stop it.

That imagination cursed him throughout his early life. Pujol was so convinced that he had a great part to play in world affairs that he was a disaster at everyday life. He was a bad student and an even worse soldier who spent all of the Spanish Civil War trying not to kill anyone. His beloved father died thinking his son was a failure. His Catholic mother was in despair.

When the German divisions began rolling through Poland, however, something changed in Pujol. His father had taught Pujol to fight for freedom and individual dignity, and the young man saw all that going up in smoke along the Western Front. He decided to take up arms in his own unorthodox way. And he had only one weapon to offer the Allies: the brain that had almost ruined his life.

Pujol and his new wife, Araceli, went to work. First he went to the British embassy in Madrid and offered his services. “Your services of what?” was the reply. He would try on four separate occasions to volunteer for the Allied cause and be shot down every time.

There was only one alternative. He would have to pretend to be a Nazi and volunteer for the German side, then turn double agent. Madrid at the time was practically controlled by the Third Reich, so this was a seriously dangerous option, but he went ahead anyway.

Pujol marched into the German embassy and soon hornswaggled an experienced Nazi spy-runner named Federico into believing his wild stories about his friends and contacts in key wartime positions. (None of these friends or contacts actually existed). To prove his bona fides to the Nazi agent, Pujol traveled to Lisbon, the WWII capitol of intrigue. In Lisbon, even the hotel chambermaids worked for one spy service or another and people sold their heirlooms and their relatives to get to the West. There were thousands of desperate men and women trying to escape Portugal. Pujol arrived and joined the sorry-looking crowds looking for a break, a way into the game.

After drifting around for days, Pujol found a fellow Spaniard who was carrying a special diplomatic visa, which would allow the owner to leave on the seaplane that flew out of Lisbon for points west every day. Pujol instantly made friends with the man (Pujol was very good at that), accompanied him to the cafés and restaurants for weeks, then set his plan in motion. He set him the Spaniard with a supply of drinks and chips at one of the local casinos, then snuck into the man’s hotel room, found the visa and photographed it. He sent the Spaniard on his way then visited a series of shops in Lisbon and had the visa reproduced down to the special stamps. The forged document was something that men in Lisbon would have killed for, and it convinced Federico that Pujol was the real thing. Soon he was snapped up by the Abwehr, the German intelligence service, and sent into action.

Pretending to be heading to London, Pujol settled in Lisbon and sent a stream of intricately detailed reports on British armaments, Allied airfields, massive troop movements, and convoys headed toward the besieged island of Malta. They were utterly convincing and 100 percent fake, cribbed from propaganda films, flyers, and phone books. When British analysts later studied the messages, they refused to believe that Pujol had never set foot in England.

Throughout his early career as a spy, Pujol was one phone call or one background check away from being executed. He lived by the slimmest of margins. “It seemed a miracle that he’d survived so long,” said his MI5 handler later on. Pujol agreed. “It was crazy. I had no idea what I was doing.”

The self-made spy finally convinced the Allies that he wanted to work for them and was smuggled into England. At his debriefing in London, he told his British handlers why he’d volunteered to fight the Nazis. His brother, Joaquin, had been vacationing in France when he came across a horrific scene: the Gestapo pulling out refugees from their hiding places in a French home and executing them in cold blood. The MI5 officer, a half-Jewish artist named Thomas Harris, listened to the gruesome tale and afterward declared that Pujol would make a “marvelous agent.”

In doing the research for Agent Garbo, my book on Pujol, I discovered what became one of the more fascinating details of his story: at the time Pujol was being debriefed, his brother Joaquin had never been to France. He’d never been out of Spain. The story was a complete fantasy, created by Pujol to make sure the Allies believed him and that he would be allowed to live out his dream.

Soon afterward, Pujol and Harris began one of the great partnerships in espionage history: they sent the Abwehr airplane manuals baked into cakes, created an army of 27 fake sub-agents to feed the Nazis fake narratives, made battleships vanish from the Indian Ocean and pop up thousands of miles away. An MI5 advance man toured the English countryside for hotels the imaginary informants could “stay” at and pubs they could describe in their bulletins. The Germans rated Garbo their best spy in England; he was even awarded the Iron Cross, something that amused Pujol to no end.

The Allies were just as impressed. Churchill read his dispatches at night. J. Edgar Hoover wanted to meet him.

When it came time to concoct a scheme to “cover” D-Day, Pujol was given the job of convincing Hitler that the Allies would attack Calais and not Normandy. Few believed he would succeed, but Garbo and a handful of other double agents began by creating an imaginary million-man-strong army. George S. Patton was assigned as commander. Made-up Morse code and stacks of Garbo’s eyewitness reports was bolstered by physical trickery: gargantuan fake oil depots, sham tanks, and airfields. One British soldier even imitated the British General Montgomery, to trick the Germans into believing that the sham invasion was real.

Pujol was nervous throughout the run-up to D-Day. He would walk the parks of central London, passing by the American G.I.’s and their British girlfriends, knowing that many of them would live or die by the lights of his acting skills. (He should have been nervous: a 1943 dress rehearsal for the landings had resulted in a total failure of the deception plan and the deaths of hundreds of French civilians). Araceli, his partner who’d helped him create Garbo, was lonely and jealous; he spent too much time with Harris, not enough with her. His marriage was breaking up.

But when the invasion came, the plot to deceive Hitler was a tremendous success. Months later, the Führer was still holding back some of his best panzer divisions, still believing that Garbo’s million-man army would appear at Calais. One message that Garbo sent on June 9th was seen by the Führer and became the key factor in keeping some of the best German divisions away from Normandy. When he met Thomas Harris, General Eisenhower told him: “Your work with Mr. Pujol most probably amounts to the equivalent of a whole army division. You have saved a lot of lives.”

The other reviews were equally strong. The British spy Anthony Blount called Pujol’s work “the greatest double cross operation of the war.” But the British historian Roger Fleetwood-Hesketh put it best: “It couldn’t have been done without him… It was Garbo’s message…which changed the course of the battle in Normandy.” Garbo emerged from D-Day as the greatest double-agent of the war, perhaps of all time.

After his services were no longer needed—MI5 tried to “sell” him to the Soviets but the traitor Kim Philby nixed the deal—Pujol and Araceli escaped to Venezuela with their small children. His attempts to start a new life ended in failure and misery. His business plans came to nothing, and Araceli left him and took the kids back to Madrid, where she married an American entrepreneur, a former body double for Rudolf Valentino. Pujol had to start from scratch. He eventually lost contact with his children by Araceli. They wouldn’t be reunited until nearly four decades later, when Pujol reemerged for the 40th anniversary of D-Day, much to the astonishment of his sons and daughter, who thought he’d died in Angola of malaria.

If Pujol had followed his talents to their natural ends, he would have become one of the great scam artists. A Bernie Madoff type. But in reading his private letters in Madrid, I was able to see why this never happened. Pujol’s operatic gift for the flimflam was paired with a set of ideals that he described in his private letters (always capitalizing the first letter) as “Humanist.” It’s an old-fashioned term, not used much anymore, but Pujol believed in it single-mindedly.

In other words, he enjoyed the game for its own sake, but he limited his victims to the Nazis. We’re lucky, in more ways that one, that this was the case.