When Tom and Terry Sullivan go to the movies, they attend the Century 16 Aurora and sit next to row 12, seat 12 in Theater I. That’s where their son, Alex, was killed when a premiere for The Dark Knight Rises became the scene of a massacre. Holding down the seat cushion, the Sullivans imagine Alex is there. They save his seat. Holding back tears, Tom calls it “the best seat in the house.”

This touching tribute demonstrates perhaps the most striking thing about Tom Sullivan: his superhero-like insistence to seek a positive response to that dark night. It has been one year since James Holmes entered that Colorado movie theater dressed in tactical gear and armed with teargas, multiple firearms, and ammunition. Thirty minutes into the midnight showing, Holmes opened fire on the crowd, injuring 70 and killing 12 people on July 20, 2012, which was also Alex Sullivan’s 27th birthday.

Afterward, online and on television, Sullivan became the portrait of the tragedy when an AP photographer captured him in an agonized embrace with his wife and daughter. While he continues to mourn, since then he has helped organize a comic-book-themed charity, led victims’ families back to the movies, and entered a tense gun-control debate as a reform advocate. In an interview at a Sonic Drive-In earlier this month, Sullivan spoke about his pained efforts to make Aurora a safer place and to help it move on. It’s a sadly common situation in the U.S., where mass shootings have greatly proliferated since the 1999 massacre at Columbine High School in nearby Littleton. Tom Sullivan’s story is unique, however, in the degree to which it is not simply inspiring, but uplifting.

Wearing a T-shirt that read “We Will Remember,” he began by describing his son as a friendly guy with a playful sense of humor and a generous smile—traits that served him well as a bartender.

Alex was also an avid comic-book fan, and his death was the catalyst for a local, then national, relief effort by the comic-book community.

***

When Jason Farnsworth, owner of Aurora’s only comic-book store, All C’s Collectibles, saw the Sullivans on the news, his heart sank. Tom and Alex were regulars and friends. That day, Farnsworth fielded several phone calls from reporters asking if he thought Batman may have inspired the killer. His only response: “I had a customer killed. If you want to talk about him I’ll talk. Otherwise I have nothing to say.”

Ironically, had the massacre occurred at a screening for a different movie, the charitable response would likely have been less robust. Over the following month, Farnsworth organized a silent auction for survivors and victims’ families, an event that attracted donations from DC Comics as well as dozens of artists, writers, and storeowners across the country. The event raised $22,000 and compelled Farnsworth to launch Aurora Rise, a Batman-themed charity whose mission is to “make the days ahead of those affected a little bit brighter.”

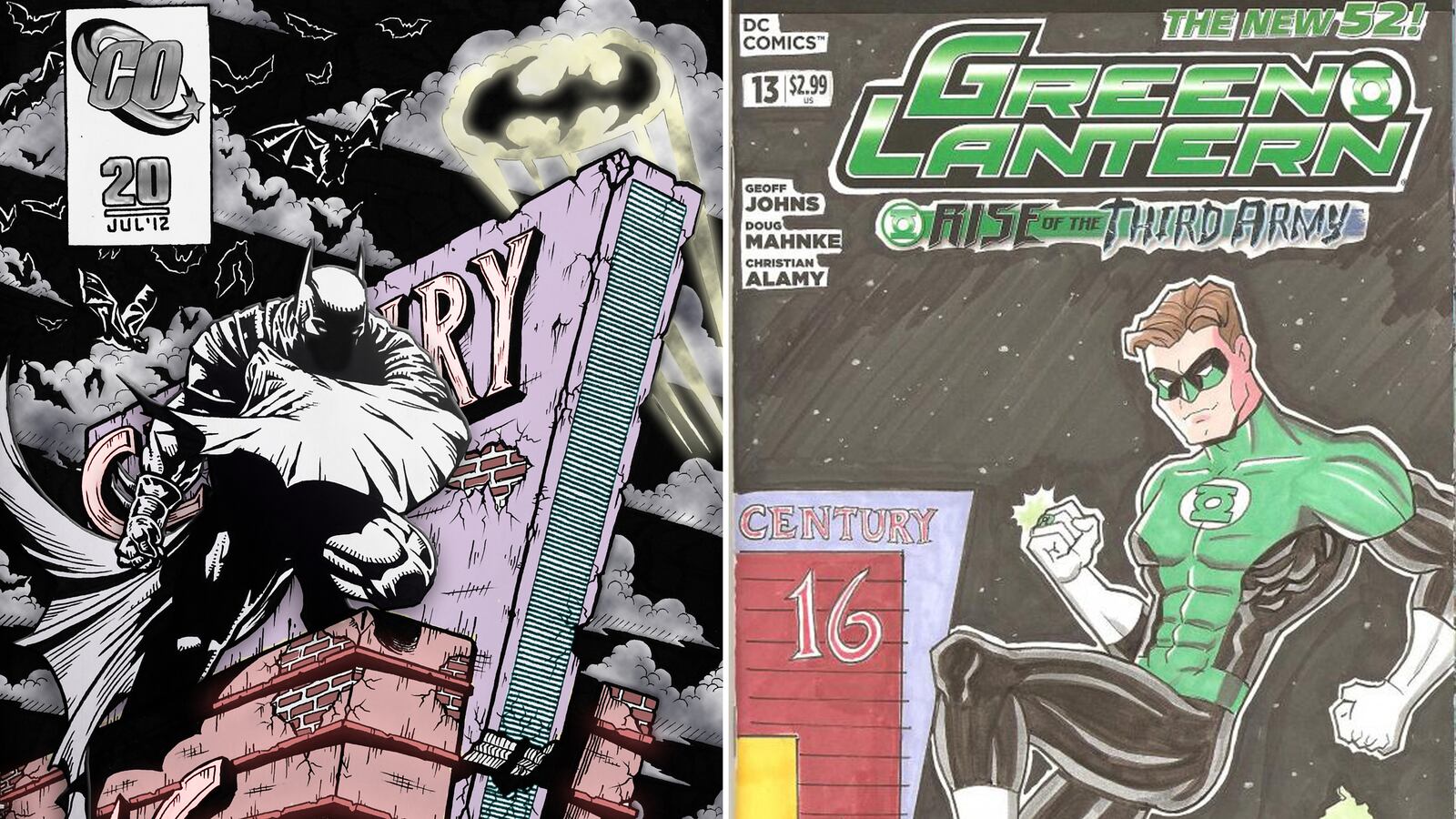

Tom and his daughter Megan Sullivan were invited to join the board. They did, and Tom’s first project was to gather artists to design commemorative artwork featuring superheroes guarding the entrance to Century theater, sending the message that it’s safe to return. The book is available for a suggested donation of $7.20 and has already benefited one young survivor, albeit in a subtle way.

A 12-year-old boy who escaped the shooting with his mother introduced himself to Sullivan at the casket viewing. His mother had worked with Alex, and they were part of the group he was with at the theater that horrific night. Handing Sullivan a copy of Green Lantern as a gesture of condolence, the boy said he and Alex had bonded over their mutual love of comic books. Alex even gave him a Batman hat while in line.

Months later, when he heard the boy was struggling in school, having trouble sleeping, and no longer visiting the comic-book store, Sullivan asked an artist to design a picture that might comfort the kid. He commissioned a picture of the Green Lantern protecting the Century theater, which he gave to the boy at an awards ceremony for Aurora’s first responders. “The kid broke into a super big smile,” Sullivan recalled. “I could see him clutching it tightly all through the ceremony. I think he was having a tough time because these were the people, the medics and police he saw that night,” he added. “I think it was all coming back to him then.”

***

Solidarity among victims’ families began to wane six months after the shooting, when Cinemark announced plans to reopen the theater with a “special evening of remembrance.” Some, such as Tom Sullivan and his family, supported the event; others were understandably enraged. Responding to invitations to the opening ceremony, 15 relatives of nine victims (including Alex Sullivan’s widow) signed a letter condemning the company for showing “ZERO compassion” for their suffering. They labeled the event a “thinly-veiled publicity ploy” intended to “divert public scrutiny from [Cinemark’s] culpability in this massacre.”

The company currently faces several lawsuits from victims’ families, who claim it is liable for wrongful death or injury due to lax security.

Setting aside the company’s motives, the Sullivans felt that returning to the theater was an important step for them and the city, which Tom outlined in an op-ed in the Denver Post. “If you truly knew my son Alex,” he wrote, “you would know that he would want me to be there, if only to show that we will not allow anyone to take the joy we shared at theaters across the metro area away from us.”

Referencing an online survey in which 70 percent of respondents supported the theater’s reopening, Tom wrote that the decision was “bigger than me or any one person … the first step in gathering and rebuilding the Aurora community.”

It would be Terry Sullivan’s first visit to the cinema since July 20, but Tom’s second. Two weeks after the shooting he visited the Aurora Movie Tavern, a dinner theater where Alex bartended, to give the manager a shot glass bearing his son’s nickname, “Sully.” He stayed for the Dark Knight Rises, sitting alone but holding a seat for his son.

“I knew there would be that point where you’re trying to imagine, well, when did this all happen? What was the last part he saw before he died?” he recalled at the Sonic Drive-In. “When it all got finished, I was crying because I knew how much Alex would have loved it.”

At the Century theater’s reopening, the Sullivans sat next to Alex’s last seat. Tom rested his arm on its seatback for most of the showing, and halfway through the movie Terry said: “I forgot how much I missed this.”

“When we walked in there, a 900-pound gorilla walked out,” Sullivan says. “We didn’t know what to expect, and now we’re comfortable again. Going to the movies is not as spontaneous as it used to be. It’s more of a concerted effort—you have to get yourself ready—but we’re working on that.”

***

Even though Colorado was home to two of the most horrific mass shootings in recent U.S. history, calls for new gun-control measures were never louder than after the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut. Sullivan himself felt compelled to lobby for change only after that massacre, as well as to pen letters of sympathy to Sandy Hook parents, something he “would never have done before,” he says.

At the capitol building in Denver, he listened to legislative debates. He attended town-hall meetings and asked Republican lawmakers to see the threat posed by loose background checks and high capacity magazines from his perspective. He offered to show them a picture of his son, but his requests were consistently rebuffed.

“People always tell me, ‘I can’t imagine what that’s like.’ But I don’t want them to,” Sullivan says. “I don’t want another father to imagine that. Those people, though—the ones that are in power and can make a difference—they need to imagine that.”

Strict, new gun regulations became Colorado law in March, but until those standards pass the U.S. Congress, Sullivan says he won’t stop lobbying. “I told [Republican congressman] Mike Coffman: “When you show up in public I’m going to be there. You’re going to see me and if you get on the wrong side of this you have to know that I’m going to be on the other side working with whoever is there to try to defeat you.”

“It’s going to inconvenience people,” he says of the gun-control measures he’s fighting for. “But if it stops those who are on the edge, makes it a little more difficult for them—that might stop them. That’s what it’s all about.”

“They say it only takes two seconds to change a magazine. But that’s two seconds Alex didn’t have,” he adds. “He was still in his seat watching the movie. He was on the streets of Gotham city right where he was supposed to be. He didn’t have a chance to move. He didn’t jump. He was sitting there having the time of his life on his birthday enjoying a movie, and someone took that away from him. Took him away from us.”

At the time of our interview, the Sullivans were unsure how they would spend the July 20 anniversary. Tom said they were unlikely to attend the city’s vigil, preferring to do something private to honor Alex’s memory and celebrate what would have been his 28th birthday.

“Some people have said, ‘You’re lucky it happened on his birthday, because that’s one less day for it to come back to you,’” he says. “I’ll have to see. The truth is we think about him all the time.

"But it’s not going to be a mournful day," he adds. "It’s going to be a celebratory day just like all the birthdays we had with him.”