The past year was remarkably notorious for the Supreme Court. Its conservative supermajority tore and tore into the very fabric of the Constitution, siding with the Trump administration—a count in October showed Trump winning 21 of 23 cases—in cases that repeatedly, and recklessly, expanded his use of executive branch powers.

The high court approved the dismissal of thousands of federal employees, massive cuts to research funding in health and education and the demolition of USAID; it allowed the U.S. military to bar transgender troops from serving and nearly obliterated precedent supporting federal agencies being independent from the President’s whims—all this primarily through overuse of their emergency docket process, or the “shadow docket.”

But you wouldn’t have known any of this reading Chief Justice John Roberts’ year-end report, which failed to address, well, anything. Instead, Roberts offered milquetoast musings on America’s legal history, determined to avoid any reference to events after the mid-19th century. 2025? Didn’t even happen! Ostensibly, Roberts wants his stroll down memory lane to emphasize this coming summer’s semiquincentennial.

That’s an occasion that will see the ball drop in Times Square; Roberts is dropping his own now—again.

Now, the report isn’t intended as a vehicle for the Chief Justice to revisit (or defend) rulings, but rather as a holistic look at the state of America’s courts. And even a cursory glance would indicate that the judiciary branch is waist-deep in the swamp—to put it politely. And it’s sinking fast.

The Chief Justice absolutely should have addressed his court’s alarming embrace of the shadow docket, an emergency hearing process that fast-tracks cases without the usual full briefings, oral arguments or even an explanation of judicial reasoning. To avoid doing so is but the latest sign that the Chief Justice shares President Trump’s vision of wielding power like a monarch, rather than a public servant in a democracy.

Use of the shadow docket is now at a flagrantly ahistorical level—the 2023-24 term saw 44 matters addressed thusly, while the 2024-25 term saw 113. Sensing an opportunity, the Trump Justice Department has sought emergency relief at a pace that dwarfs that of previous administrations. Combined, the Obama and Bush II presidencies made eight such requests. The Trump administration made 19 in its first 20 weeks.

The practice is generating dissension among the justices themselves—arch-conservative Justice Samuel Alito told an audience at Notre Dame law school that the court’s use of the “emergency docket” is legitimate and, of course, took exception to the opposing view that its use makes the court a “cabal” working in the stealth of night. In a scathing dissent that same month, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, of the court’s liberal minority, criticized her conservative peers’ use of the shadow docket, writing: “The only rules (are) that there are no rules, and that the Trump administration always wins.”

And it has also seen the high court bickering with lower federal courts. Conservative justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh have both harshly criticized lower court rulings, lecturing their fellow life-tenured jurists like angry parents. What they say is right simply because they say so, never mind that it’s without guidance or precedent. (And you’re grounded!) At a hearing in September, meanwhile, a federal court of appeals judge said that SCOTUS had left his court “out here flailing;” that same month, a federal trial court judge said the emergency orders “have not been a model of clarity.”

As Professor Steve Vladeck, a Supreme Court expert and Constitutional law professor at Georgetown, put it: “The justices seem more concerned with lower courts correctly reading the tea leaves in their (often unexplained) rulings than with the executive branch behaving properly before the rest of the federal judiciary.”

But again, Roberts said nothing about this. His intent appears to be to highlight, in his view, the significance of the Declaration of Independence never having been codified into U.S. law. He seems to want to make the point that it needn’t be, because it provided the aspirational pathway to the Constitution and countless other subsequent examples of legislation, often hard-fought, that today underpin essential American values and freedoms—at least until this very SCOTUS rolls them back. He emphasizes this in his conclusion by quoting President Calvin Coolidge, a man often criticized as having blithely led America into the Great Depression:

“Amid all the clash of conflicting interests, amid all the welter of partisan politics, every American can turn for solace and consolation to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States with the assurance and confidence that those two great charters of freedom and justice remain firm and unshaken. True then; true now.”

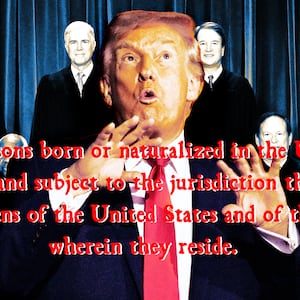

But Roberts’ determination to live in the past portends poorly for the future of American law and the lives of Americans. The high court is poised to further erode the Constitutional balance of powers in an expected ruling that will overturn the 90-year-old precedent protecting the independence of federal agencies. And, this spring, they will entertain Trump’s argument that he can ignore the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship.

His ham-fisted paean makes it plain that the Chief Justice doesn’t get it. The Supreme Court’s job isn’t about aspiration. It’s about the law. “True then; True now.”