What happened to the WASP establishment?

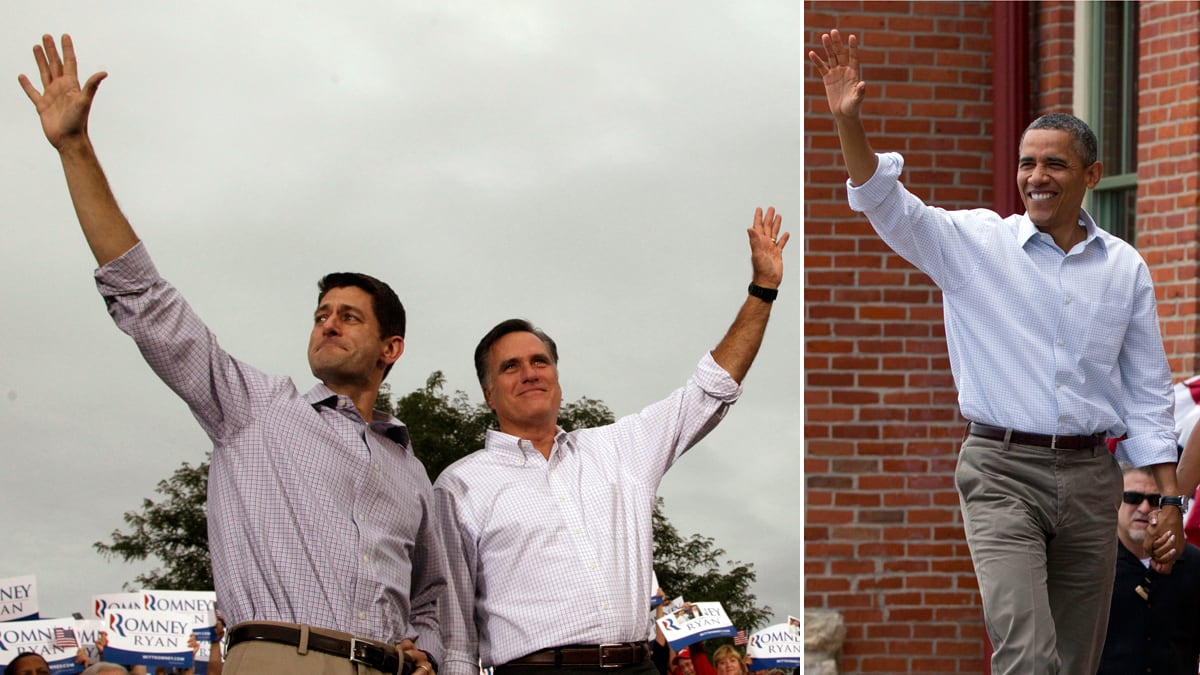

Mormon Mitt Romney’s selection of Catholic Paul Ryan as his running mate is an historic moment:

For the first time in the 236-year history of the Republic, no one on either presidential ticket belongs to the once-prototypical American group, the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant.

Until 2008, when black Protestant Barack Obama ran with Catholic Joe Biden, we’d never had even one party offer a non-WASP ticket.

That in itself tells a lot about the transformation of our political culture, our demographics, and where we have come as a nation. It helps explain the Tea Party and the Republican insurgency, even though some of the insurgents, like Ryan, are themselves non-WASPs.

Looking past the presidential contenders, John Boehner, the Speaker of the House, is Catholic, and Harry Reid, the Senate majority leader is Mormon. There’s not a WASP to be found among the nine justices of the Supreme Court (one black, five Catholic, three Jewish). That’s a clean sweep of all three branches of government.

Given the way we defined ourselves through most of those 236 years; given nearly two centuries of WASP history and tradition; given the dominant figures of our culture—our heroes, our pioneers, our leaders in business and industry, our thinkers, writers, the popular symbols that brought us together, the people who were held up to immigrants as models of what they should become as Americans—our new non-WASP leadership group is itself a powerful symbol of our shifting national identity.

It’s been coming gradually, as, given our history of immigration, it inevitably would. In 1962, just 50 years ago, the journalist Richard Rovere published his classic semi-facetious essay, The American Establishment, a group he called “a more or less closed and self-sustaining institution that holds a preponderance of power in our more or less open society.”

In his piece, that establishment was made up of leaders of banking, partners in the big Wall Street law firms, directors of the major foundations, diplomats, members of exclusive clubs, most of them Ivy Leaguers—nearly all of them patricians, and WASPs. They were the political and social moderators, the men (yes, all men) whom other well-connected men called or met at their clubs when they wanted to get something done. They were, most of them, moderate Republicans. Extremists were by definition not qualified. They were the fixers.

There’s no such thing today, even as a figure of speech or as a clever writer’s conceit, and a lot of us might say that it’s sorely missed. What’s today referred to as the “Republican establishment” doesn’t have the remotest connection with anything that anyone a generation ago would have recognized as a real establishment, either in this country or in England, which long had a real establishment. It merely refers to the men (and a rare woman or two) who were the party’s leaders before the 2010 election.

A two-year-old “establishment” is an oxymoron.

What’s certain is the extent to which the new non-WASP political leaders reflect the nation’s changed—and changing—demographics and the changing political culture and attitudes that have accompanied it. That, too, makes for a long list: the liberation and empowerment of women; the rapidly growing Latino and Asian populations; the election of our first black president; the rapid acceptance, especially by the young, of gay marriage (interracial marriage went in a generation from a charged topic to one so widely accepted as to no longer warrant discussion); and the growing recognition of the explosive economic and political power of China, India, and other non-Western nations, and with it the erosion of the belief in our exceptionalism.

Perhaps least recognized on that list is the pervasive influence of the American literature, art, music, food, religious beliefs and ideas produced by the great diversity of African-American and immigrant cultures—Irish, Jewish, Italian, Indian, Japanese, Latino, Russian—that a century ago would have been regarded as altogether foreign. In the past half-century, the carriers of the traditions of Melville, Hawthorne, and Twain, more often than not were named Mailer, Malamud, Roth, Baldwin, Ellison, or Morrison. Forty years ago, when I published a book called The Decline of the WASP, even I thought it was a little smart-assed. It turned out to be closer to the mark than I thought, maybe even prophetic.

It’s not surprising that the great changes of the past few decades would produce a major backlash in our social life and politics, the Birther movement most obvious among them. The laws to deny illegal immigrants housing and jobs or to require voters to show photo IDs or other forms of identification are partly a political ploy by Republicans to keep poor people and minorities, most of them Democrats, from the polls, but they also trade on the nativism and xenophobia generated in every prior era of great demographic change.

We’ve seen such things many times before. A century ago we weren’t certain whether the new immigrants from the alien “races” of southern and eastern Europe could ever become Americanized, whether they would ever learn English or whether their children could ever be educated. A hundred years ago Armenians had to go to federal court to be declared white and thus entitled to be naturalized. Were Poles really white? Jews? Italians?

The “benchmark” list of this year’s political leaders, notwithstanding the backlash, is evidence that all those immigrants of the turn of the last century have indeed been Americanized, that blacks could attain the highest office in the land, and an indication that our latter-day immigrants could be as well. Justices Antonin Scalia and Samuel Alito are both sons of Italian immigrants; Justice Sonia Sotomayor is of Puerto Rican descent; Justice Clarence Thomas is the son of Gullah-speaking parents who were, of course, descendants of slaves. None of them would have been regarded as fit for even a high-school education a century ago.

But despite fears on the right of a white culture left behind and triumphalist rhetoric on the left about an emerging Democratic majority powered by our growing Hispanic population, the new, non-WASP members of our political elite are also a reminder to both parties that immigrants, their children and grandchildren, and the grandchildren of slaves, who for most of the prior century had generally been categorically regarded as comfortably Democratic and vaguely liberal could—like the Scalias, Alitos, and Thomases—become among the most conservative voices in American government.