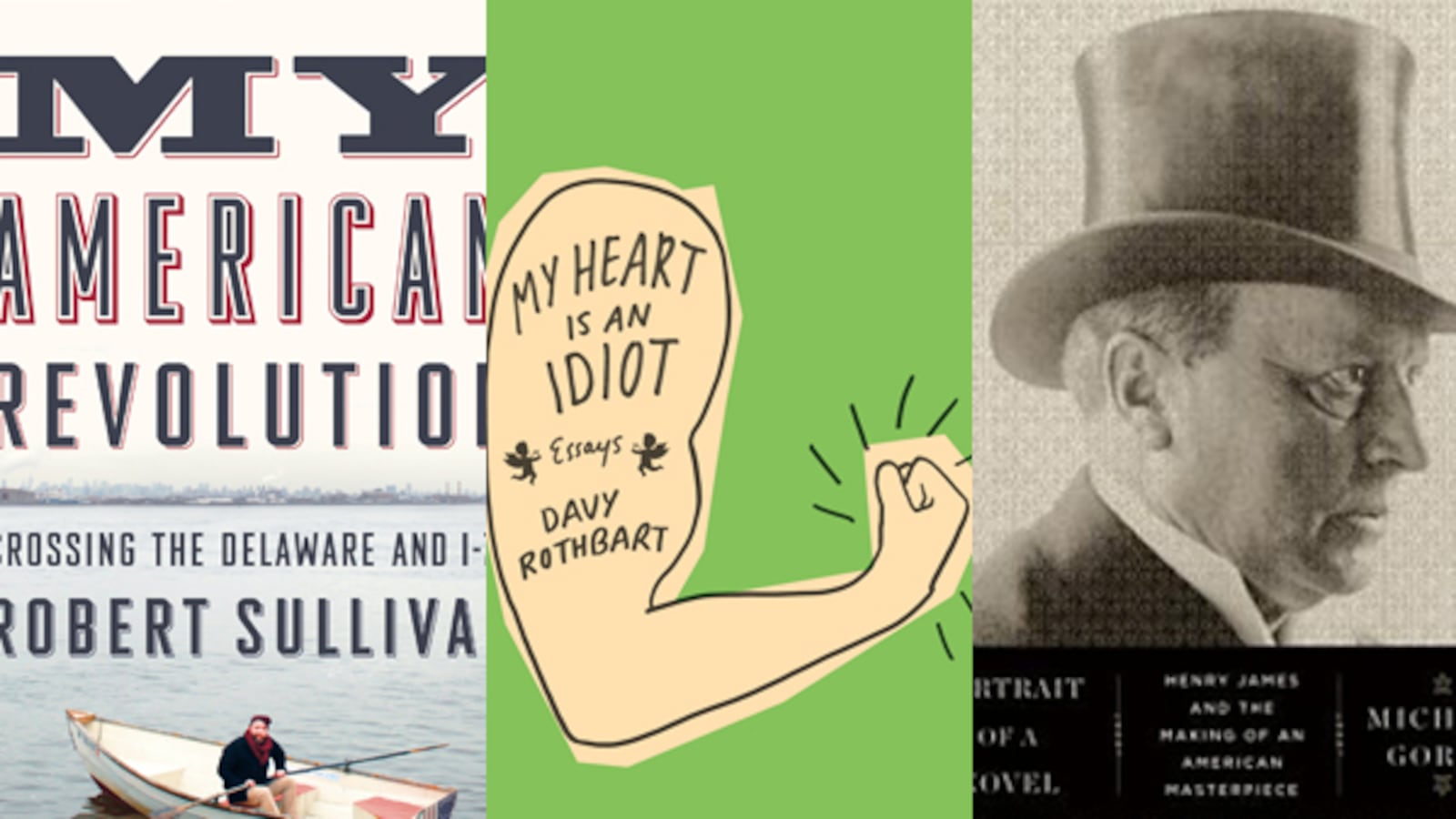

My Heart Is an Idiot: EssaysBy Davy RothbartA young essayist is often a victim of his own open heart.

Rothbart possesses two attributes that would be enviable for any essayist to have: a near-complete lack of cunning and an incurable sensitivity. The former sends him rushing headlong into mistakes that a more circumspect (and boring) person would see coming from a mile away, and the latter converts this ineptitude into artistic experience. In his new book of essays, the NPR contributor covers episodes from his romantically fraught life that range from the light (a frat-house liaison centered around a game of beer bong) to the life-and-death (the discovery of a body floating in the backyard pool of a romantic conquest). The book also includes a strong entry in that which has nearly become a genre of its own, the 9/11 essay, which is refreshing in its utter lack of pretension. There is a strain of modernity here, in the slang and bass-heavy hip-hop that dresses the stage of Rothbart’s life. But he operates in a mode as old as American letters—aw-shucks credulity mixed with an observant intelligence. It also helps that extraordinary events seem to seek him out and present themselves as perfect essay fodder. Or perhaps more fairly, we can credit Rothbart in finding the extraordinary in events that a less tuned-in person might allow to pass them by.

Laura Lamont’s Life in PicturesBy Emma StraubThe odd, glamorous, and complete life of a starlet in Hollywood’s golden age.

If you’re seeking metaphors for America, Hollywood would be a good place to start, especially during its golden age. The opulence, the allure, the ability to catapult a nobody into wealth and status based on what we hope is a meritocracy, and of course the fact that it’s all a fiction. In her first novel, Straub, author of the story collection Other People We Married, tells the life story of Elsa Emerson, a blonde Wisconsinite who makes the same pilgrimage to Los Angeles that so many thousands of our attractive youth have made since the invention of the moving picture. She wants to be an actress, with all of the glamour attendant thereto, but she also seeks the promise of compartmentalizing her damaged soul. She gets the chance to do both after a studio executive rechristens her Laura Lamont. “After that afternoon, she was always two people at once, Elsa Emerson and Laura Lamont ... Elsa wondered if it would always be that way, or whether bits of Laura would eventually detach themselves, shaking off Elsa like a discarded husk.” Straub moves Lamont through a full spectrum of archetypes over the course of her life, from doe-eyed Midwestern neophyte, to glamorous starlet in furs, to aging icon ready for her close-up. These figures are all familiar, but Straub keeps the dramatic twists coming—when dealing with Hollywood, a writer is going to have to grapple with cliché.

The Forgetting Tree: A Novel by Tatjana Soli The trials of a strong California woman who learns to love the land.

When the themes of a novel are so clearly a certain set of the Big Ones (family, loss, illness, forgiveness, and the like), it can run the risk of falling into saccharine Hallmark territory. To keep a story like this vital and compelling, rather than merely appealing to those more manipulative of our emotions, the characters must stay pinned to a believable reality, with a touch of darkness. Soli does just that. The book centers around Claire Baumsarg and her family, who run a California citrus farm that feels right out of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, where the land is unforgiving, irrigation is paramount, and evil lurks in the recesses of the mundane. It’s a hard life to begin with, even before a series of trials are visited upon them. The first, a tragic and violent death, hits the family like a comet, and the second, an illness that strikes Claire years later when her familial circumstances have changed, tests the ability of both her body and her spirit to endure. The story here is complex and expansive, and Soli’s prose is reminiscent of Eudora Welty’s. Like that writer, Soli’s sentences are tied to the land, and the effect is that as much as this is a story about people, it is also a story about place and the imprint that each makes on the other.

Portrait of a NovelBy Michael GorraThe story of a man and his masterpiece that helped bring literature into a new age.

Henry James once described the “house of fiction” as one that has “not one window, but a million—a number of possible windows not to be reckoned.” In his metaphor, the novelist stands within the house and looks out through any one of these many windows onto all manner of human experience transpiring in the external world. But in Portrait of a Novel, Smith College professor Michael Gorra reverses the metaphor; he stands with the reader on the lawn and the balconies and looks into the many windows of James’s life, peering in on both the psychological and biographical circumstances that helped shape his masterpiece The Portrait of a Lady. The book is part scholarly yet compelling close read of that text, part biography, and part travelogue—Gorra retraced many of James’s expatriated steps though Europe. The author’s encyclopedic understanding of not only James, but also his influences and contemporaries, offers a thoroughly illustrated and appropriately tumultuous picture of fiction’s awkward adolescence between stilted Victorianism and modernistic messiness. The reader does not have to love or even be particularly familiar with James’s work to enjoy this book; this is as much a story about the creative process itself, or the function of genius, as it is about any particular product.

My American Revolution: Crossing the Delaware and I-78 by Robert Sullivan A patriot looks to re-create some of the adventures of our war for independence.

Historical reenactors refer to what they do as “living history,” the idea being that it’s easier to learn from a three-dimensional experience than is from a book or lecture, because it establishes a physical connection with the past. It was something like this desire, familiar to most amateur history buffs, that drove Sullivan (who penned narrative nonfiction books like Rats and Cross Country) to relive some of the iconic deeds of American Revolution, such as crossing the East River to Manhattan in a small boat in homage to George Washington’s escape after the disastrous Battle of Brooklyn. Sullivan is himself a New Yorker, and his zeal for local history comes across in the way that he treats each task with enthusiastic respect. For him, hiking through New Jersey along the path of Washington’s troops is more than a hike—it’s a communion with our shared past that bears an importance beyond mere observation. This is half history and half just good fun. There is, after all, nothing particularly historically edifying to be gleaned from, for instance, Sullivan’s dogged attempts to send a signal to the city from the hills of New Jersey. But it’s inspiring to watch him attempt to capture even the tiniest bit of the audacity of the American founding.