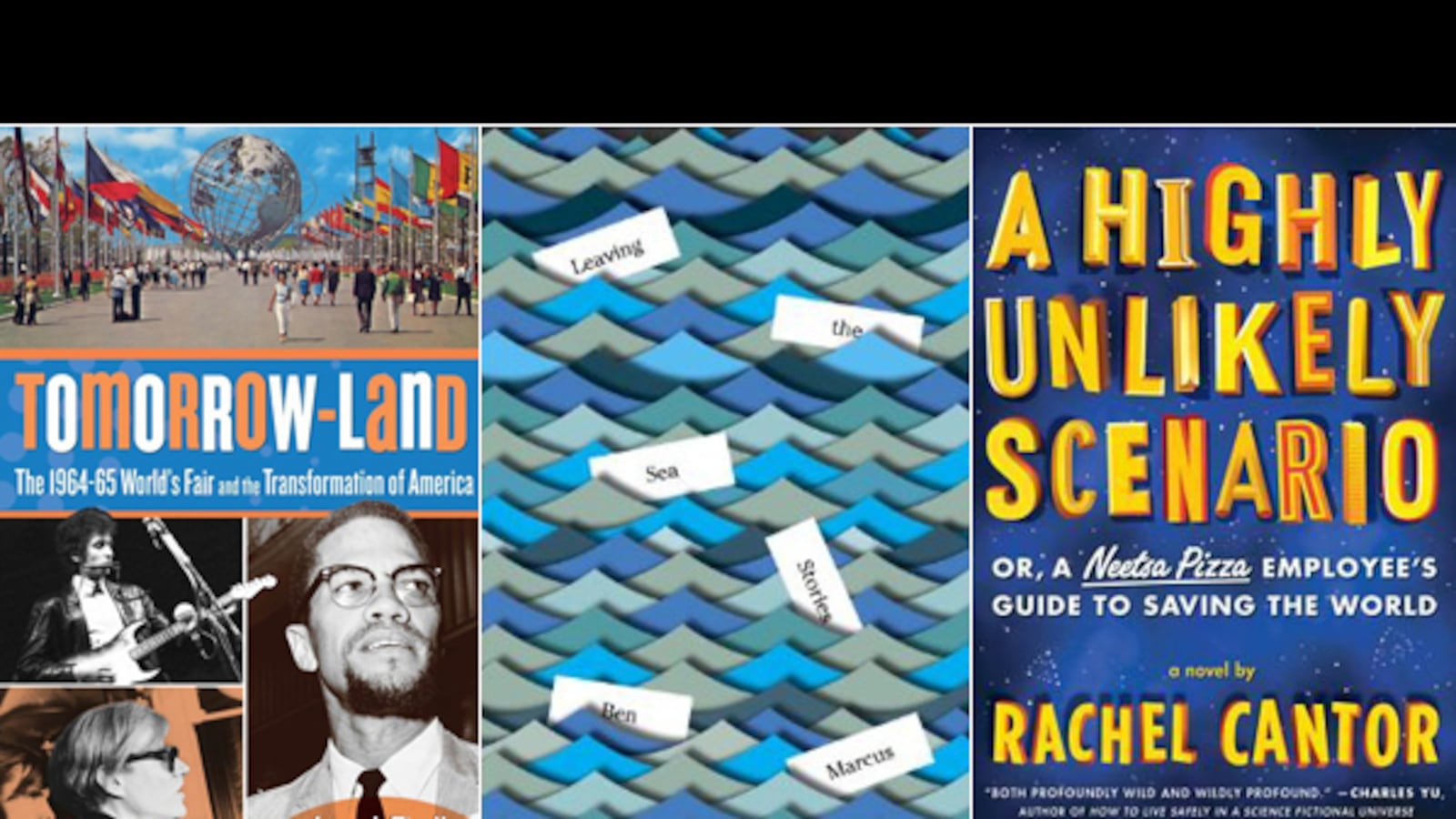

edited by Joseph Tirella

A little more than a week before the 1964-65 World’s Fair was set to open its gates in Queens, The New York Journal-American ran a front page story charging that the mural Andy Warhol had created for the fair—a mural commissioned by architect Phillip Johnson—depicted, quite literally, the city’s worst face—or rather, faces. Warhol’s painting featured 22 images of the city’s 13 Most Wanted Criminals, “resplendent in all their scars, cauliflower ears, and other appurtenances of their trade.” Within days, at Johnson’s suggestion, Warhol’s work was completely painted over. It wasn’t exactly censorship at “master builder” Robert Moses’s hands, but to Warhol, it felt that way. In frustration, he made a new painting, this one featuring 25 silk-screened images of the president of the World’s Fair Corporation. He called it “Robert Moses Twenty-Five Times.”

This episode is just one of many peculiar moments of cultural confluence writer Joseph Tirella recounts in Tomorrow-Land: The 1964-65 World’s Fair and the Transformation of America. Though fair-goers would never see either, both of Warhol’s paintings captured something essentially true about New York’s contradictory nature. It was a city where the whimsy of Warhol’s Pop Art could co-exist (sort of) with Moses’s unrelenting vision of urbanism. It was also a city where, on the fair’s opening day, President Johnson’s praise of the fair’s lofty ideals of “peace through understanding” were nearly drowned out by civil rights protestors chanting “Jim Crow Must Go!”

In Tomorrow-Land, Tirella captures the complexity of a World’s Fair that was ultimately emblematic of its times: “It espoused noble ideals, yet failed to live up to them; it purportedly sought peace but often sowed conflict; despite the critics, it did celebrate art, but all the while preached the Gospel of Commerce and Industry.” Yet, in the end, Tirella argues, the World’s Fair left behind more than the hollow stainless steel Unisphere looming in Flushing Meadows Park. Its global vision of multiculturalism ushered in a new era of immigration and fostered a spirit of pluralism that has defined America since.

by Ben Marcus

One of the early stories in Ben Marcus’s new collection Leaving the Sea finds a writing instructor at sea in every sense of the phrase. As he teaches a course to students on a cruise, Fleming questions his own abilities—as an instructor, a writer, a husband, and even as a character in his own story: “What Fleming was missing was a home and family and self that had never quite come to be, which is maybe why he was on a boat now with strangers, pitying himself.” The joke in “I Can Say Many Nice Things” is on Fleming but Marcus is too skilled to let his protagonist off with an awkward laugh. He lets Fleming writhe: “What happened to him needed to be revised until he could find it believable. Or, he needed to be revised.”

It’s in these moments of sharp discomfort that Marcus thrives; these are above all, tales about characters on the edge. There’s Julian, a desperate young American seeking treatment for his rare auto-immune disease with experimental treatments in Dusseldorf. His outlook turns bleak and his behavior erratic as he confronts the reality of his health. In “What Have You Done,” the man on the brink of an implosion is Paul, a father and husband who turns into a cruel child back in his family home. “Perhaps there was something about sitting at this table that had made him take the low road so hard and fast,” he thinks, “The table, his room, that red chair, the house, the whole city of Cleveland.”

It’s a recurring theme in Leaving the Sea that violently destructive forces lurk both inside and out. One particularly chilling story, “The Loyalty Protocol,” imagines a society on the cusp of collapse, a world where community-wide disaster drills are a regular occurrence, and where, during such a drill, a responsible man can be castigated for attempting to protect his adult parents. In Marcus’s terrifying rendering, social rules unravel just as speedily as natural ones do. People drop dead. “Safety” protocols prove inscrutable. Can anything ultimately hold the chaos at bay?

by Rachel Cantor

Sci-fi and Jewish mysticism may seem to be unlikely bedfellows, but Rachel Cantor pairs them forcefully in A Highly Unlikely Scenario, a charmingly odd story about (as its subtitle hints) saving the world. Cantor’s debut novel is set in a future where the world is run by fast-food corporations like Neetsa Pizza, a pizza chain obsessed with Pythagorean teachings. Employees of Neetsa, like Leonard, who works remotely as a cultishly constrained telephone customer service agent (his workspace is his bedroom, completely painted white).

In addition to his basic schooling in Neetsa doctrine, Leonard’s professional development with “innovative aptitude testing, exhaustive training, thoughtful supply of easy-to-use Pythagorean materials,” and the “provision of periodic ‘refresher’ updates.” None of this, however, is of much use when Leonard gets a mysterious call from another time. Instead, he finds himself leaning on the snatches of stories and songs his grandfather tried to pass onto him before his death as he is drawn deeper into a plot thickened by symbols and signs, time travel, and of course, the urgent need to save the world.

Ultimately, the storyline Cantor has crafted is too kooky and convoluted to be compelling. But Leonard’s accomplices—a resourceful girlfriend named Sally, a spunky, precocious nephew named Felix, and a red-headed revolutionary sister named Carol—are so likeable it’s easy to overlook the plot. Ultimately, more than incantations and codes, it’s family Cantor cares about. A Highly Unlikely Scenario is about just that: Familial wisdom and love lost and found and shared anew, finally, conquering all.