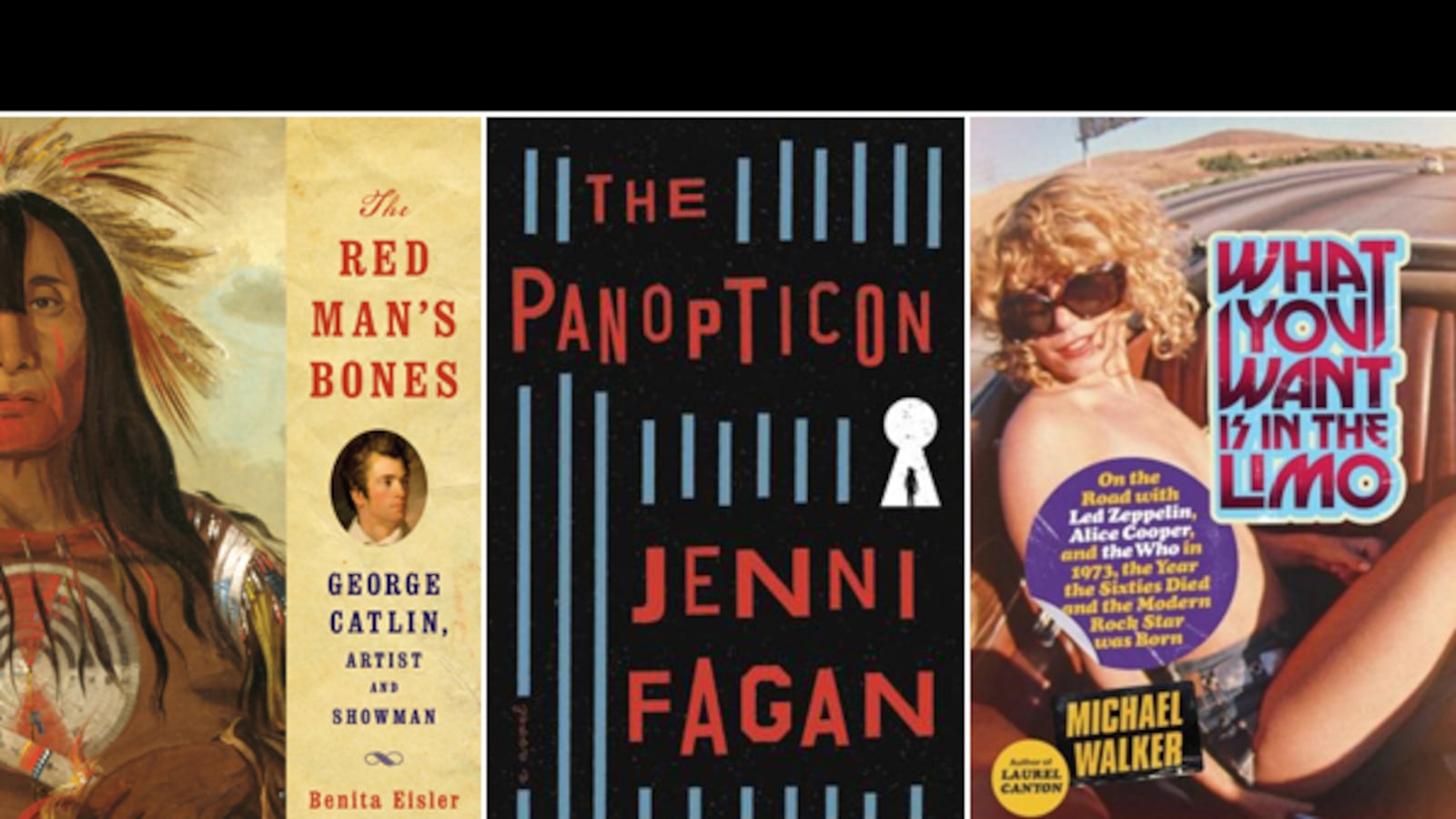

The PanopticonBy Jenni Fagan

A teenage heroine is sent to a reformatory in this dystopian novel.

Anais Hendricks, the 15-year-old heroine of Fagan’s debut novel, has been in and out of foster homes and endured a hardscrabble life, including finding her beloved foster mother stabbed to death in the bathtub. “I’ve moved fifty-one fucking times now, but every time I walk through a new door I feel exactly the same—two years old and ready tae bite.” The “tae” is not a typo; it’s Fagan’s style, and it calls to mind fellow Scottish writer Anthony Burgess, whose novel A Clockwork Orange used similar lexicographic liberties to reinforce a theme of teenage dystopia. Anais is a suspect in the assault of a policewoman who is in a coma, and she is sent to the panopticon, a C-shaped former prison and mental institution that is now a teenage reformatory. “There is a surveillance window going all the way around the top and you cannae see through the glass, but whoever, or whatever, is in there can see out. From the watchtower it could see into every bedroom, every landing, every bathroom. Everywhere.” Anais recounts at length her use and enjoyment of drugs (LSD is a favorite). She is also a serial masturbator (“the most in a row’s fourteen or fifteen”) and a tough fighter (“I’m a pacifist really, but if you dinnae fight—you’ll just get battered”). Yet she’s charmingly self-aware and oddly endearing. “I’m so imperfect it’s offensive. Totally and utterly fucked in fact—but I like pillbox hats.” One of the questions in this ambitious novel is whether Anais can become less offensive and more redeeming. Big Brother will be watching … perhaps.

The Wet and the DryBy Lawrence Osborne

Hunting for drinks across the Muslim world, where alcohol is largely outlawed.

Alcohol, like all intoxicants, has a diminishing rate of return. Osborne, the author of the wine book The Accidental Connoisseur, notes that the poet Pindar described Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, as “the pure light of high summer,” a summation that invokes warmth and comfort while obliquely acknowledging the inevitable comedown. Osborne ponders the pros and cons of alcohol as he hunts out drinks in Muslim countries, where alcohol is largely outlawed and Islamic militants have been known to bomb bars. Osborne finds many Muslims who have gone beyond the rigidity of the Koran to draw their own conclusions on why alcohol is bad: “It took one out of one’s normal consciousness. It therefore falsified every human relationship, every moment of consciousness. It falsified one’s relationship to God as well.” Osborne’s irreverence (“I might eventually stumble across that most delightful phenomenon, a Muslim alcoholic”) is both unseemly and enjoyable, much like alcohol. “There is an undeniable thrill about getting liquored up in Islamabad. The possibility is very real that as you sit discreetly sipping your Bulgarian merlot from a plastic bag, you will be instantly decapitated by a nail bomb. You might even be shot in the head for the simple crime of drinking. Your chances of dying in this way are not astronomically high. But nor are they astronomically low.” In Osborne’s case, he’s more likely to die of cirrhosis of the liver, and he’s probably fine with that.

Shot All To HellBy Mark Lee Gardner

The story of the infamous bank robbery in Northfield, Minnesota, by Jesse James and his gang.

Gardner, who told the story of Billy the Kid and Sheriff Pat Garrett in To Hell on a Fast Horse, deftly describes how the attitudes of average citizens can help to explain the enduring myths of the Wild West. This time he takes on one of the most famous bank robberies in history, the Northfield Raid in Minnesota in 1876, which led to the downfall of the gang led by Jesse James and his brother, Frank, and included the Younger Brothers (Cole, Jim, John, and Bob). But the actions of the most famous participants were not what stuck with me—it was the reactions of average citizens both during the raid and after. “It was the townspeople’s money in the bank, and as was the case with all banks at that time, those deposits were uninsured,” Gardner notes. “In effect, the outlaws were robbing each citizen individually…which was plenty good reason to put up a fight.” The citizens shot and killed two members of the James-Younger gang during the robbery, which lasted “no more than ten minutes, perhaps as few as seven” and netted the unimpressive sum of “$26.60 in coin and scrip.” A bank teller was executed (allegedly by Frank James) for not opening the vault, and Cole Younger allegedly shot and killed a resident on the street. Blood had been spilt by both sides, and when the remaining robbers fled into the wilds of Minnesota, more than a thousand men gave chase. And so, years later, when Frank James was eventually caught and brought back to Minnesota, the reaction of the people seems bizarre. “Large crowds flocked to the jail, where they greeted him like a visiting dignitary,” Gardner writes. “Or, as one Minnesota newspaper put it, the ‘darling of Missouri society.’ He politely shook hands with his visitors and told them he was glad to meet them.”

What You Want Is in the LimoBy Michael Walker

How Led Zeppelin, The Who, and Alice Cooper invented the modern rock star.

You don’t have to love the music or personas of the three bands highlighted here—Alice Cooper does nothing for me—to appreciate the vital roles that all three played in creating the modern rock star. Led Zeppelin manager Peter Grant negotiated full artistic control of the band’s music and sliced promoters’ concert cuts from 40 to 10 percent. “He single-handedly rewrote the rules of engagement that record companies and promoters had to follow when dealing with Zeppelin, which were quickly adopted by grateful fellow managers and became industry standards,” writes Walker, author of Laurel Canyon: The Inside Story of Rock-and-Roll’s Legendary Neighborhood. He is convincing and entertaining in explaining why 1973 was a seminal year in rock. “A new generation of fans too young for Woodstock inherited the tropes of the sixties minus the boring poli-sci socio-overlay. Thus do peace, love, and understanding devolve into sex, drugs, and rock and roll—the sex being younger, the drugs harder, and the rock and roll louder, longer, and infinitely more belligerent.” Pete Townshend and the Who were one ’60s band that successfully transitioned into the new era and beyond. Unlike Led Zeppelin, the Who were widely respected by critics, who largely lauded Townshend’s avant-garde rock opera Quadrophenia. Meanwhile Cooper, with his “trademark psycho-clown mascara” and routine of getting theatrically murdered on stage, led a band that was “the first to fully integrate a theatrical sensibility into rock performance.” He did so before David Bowie or Kiss, which lands him a spot in Walker’s story.

The Red Man’s BonesBy Benita Eisler

George Catlin, now forgotten, was once world famous for his paintings of Native Americans.

George Catlin is not a household name, but he was the first artist to live among Native Americans, and you’d probably recognize many of his portraits and pictorial narratives. His depiction of the torturous Mandan coming-of-age ritual, in which young men are hung, skewed, and flayed, is probably his best-known work. Eisler, who has written biographies of Lord Byron and George Sand, notes that in the movie Dances With Wolves, director Kevin Costner re-created one of Catlin’s great paintings of a buffalo hunt. To borrow a term from Dances, Catlin was a “big tatanka” in the 19th century. But he couldn’t turn his fame into a decent living. Unable to sell his Indian collection to Congress, Catlin went to Europe and was feted for a time for his exhibited work. But the exigencies of making ends meet prompted him to make some questionable financial decisions. When he became a showman and featured Indians in a precursor to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, his reputation suffered. Catlin stayed in Europe for 30 years and adopted an “eccentric and marginal life,” Eisler writes, “his only companions a cage of white mice.” She argues that Catlin’s art is now so recognizable that the artist has been obscured, and makes a compelling case. Catlin died in 1872 and is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, but even that is fogged in doubt. “Caitlin’s grave was once marked by a small blank stone,” Eisler writes. “But that has been missing for years, and no one is sure anymore of his precise burial place.”