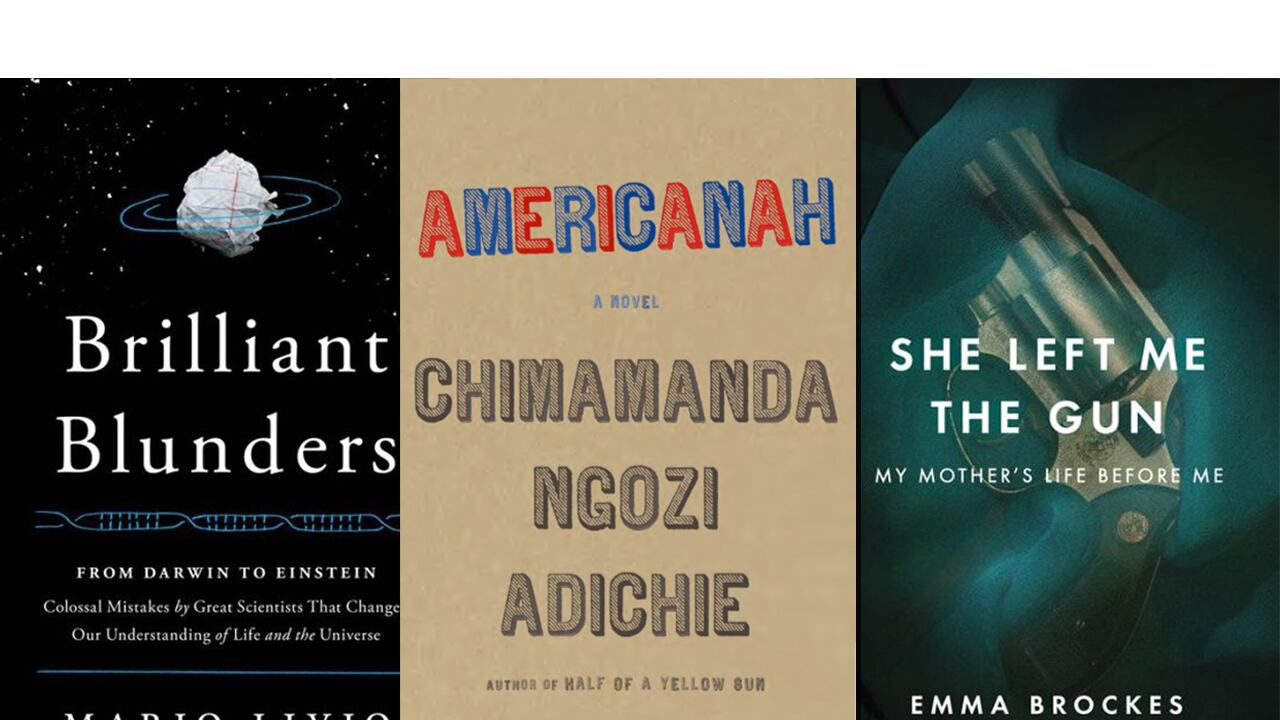

Americanah By Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

A woman struggles to assimilate in Nigeria after living in the U.S. for 13 years.

Ifemelu, the heroine of Adichie’s third novel, fled Nigeria as a college student when universities went on strike to protest the country’s military regime. “A piercing homesickness” has spurred her return to Lagos, but she also wants to reunite with her lost love, Obinze, who is married. But after living in the United States for 13 years, she is shocked by how much Nigeria has changed. (“Commerce thrummed too defiantly.”) “And so she had the dizzying sensation of falling, falling into the new person she had become, falling into the strange familiar. Had it always been like this or had it changed so much in her absence?” Ifemelu used to have a convincing American accent, but it “creaked with consciousness, it was an act of will. It took an effort, the twisting of lip, the curling of tongue. If she were in a panic, or terrified, or jerked awake during a fire, she would not remember how to produce those American sounds. And so she resolved to stop.” Her friend Ranyinudo chides her: “You are looking at things with American eyes. But the problem is that you are not even a real Americanah. At least if you had an American accent we would tolerate your complaining!” She, according to the slang term pinned on her by her Nigerian friends, is now an “Americanah.” This tug-of-war between assimilation and retention touches all aspects of her life, and Ifemelu chronicles the ongoing battle in a popular blog called Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black. Adichie deftly blends the blaring, staccato blog posts into a subtle, sweeping novel that is long on considerations of what it means to be American, for both foreigners and natives.

—Cameron Martin

Angel Baby By Richard Lange

A crime novel that follows the exodus of a woman from Mexico to Los Angeles.Almost every character in Lange’s latest crime novel is made desperate by personal demons, and this struggle creates a fast-paced thrill ride that hops back and forth between Mexico and the United States. There is a sadistic drug lord called El Principe; a corrupt border patrol guard named Thacker; an alcoholic, guilt-wracked human smuggler named Kevin Malone; and the former prostitute Luz, who will tie their lives together in a Tarantino-like vortex of mayhem and violence. Luz is the kept woman of El Principe, a Machiavellian Mexican gangster who plies her with drugs to keep her down, and rapes her when she makes him angry. Luz has finally had enough, and she wants to get back to the U.S. to reunite with her daughter, Isabel. When El Principe leaves the compound one day, Luz sees her opportunity. She steals a bundle of cash and his personally inscribed handgun, but when she tries to slip out unnoticed, she runs into the bodyguard. Luz reacts like a wounded animal: “She racks the slide and points the .45 with both hands, doesn’t flinch at the BOOM BOOM BOOM when she squeezes the trigger.” Luz gets away and hires Malone to take her over the border, where Thacker and others are waiting to snag her. As Luz progresses “toward Isabel, her lodestar,” she attracts a cast of characters who are similarly trying to survive, or perhaps just hoping to die with some dignity.

—C.M.

She Left Me the Gun By Emma Brockes

A grieving daughter travels to South Africa to investigate her mother’s life before her.

Journalist Emma Brockes puts her investigative skills to good use after her mother, Paula, dies from cancer, leaving unanswered questions about her early life in South Africa. The book begins as a quest to discover more details about the sexual abuse Paula and her siblings suffered at the hands of their father—it was so serious that it subsequently led to legal proceedings. But She Left Me the Gun morphs into a memoir about the power of escape and reinvention. Brockes has the voice of a novelist, and her relatives could be characters in a Dickens story. Cultural misunderstandings in South Africa range from hilarious (”pink champagne ... an even worse crime than white footwear”) to terrifying (bikers sporting swastikas). As the truth of what this family endured emerges, Brockes realizes her mother’s unwillingness to talk came not from disdain but rather from her will to survive. As her father warns her to be careful about “how much of this you want to know,” She Left Me the Gun illustrates not only Paula’s bravery, but the amount of courage it requires to unearth a family history buried under years of suffering and denial.

—Jessica Ferri

A Short Tale of Shame By Angel Igov, translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel

A chance encounter on the road helps four people to realize they have more in common than a shared acquaintance.

Boril Krustev is a washed-up Bulgarian rocker who is on the run, avoiding the recent death of his wife and an estranged daughter when he picks up three hitchhiking college students. Early in this brief novel it’s revealed that the three just happen to be friends (or, actually, frenemies) of his daughter Elena. They travel to Greece, and as they ruminate about the past, they discover that they share a sense of guilt over the damaged relationships in their lives. For his part, Krustev is jealous of the three free-spirited young people, who seem blissfully intimate, but in actuality are in constant conflict. Told with alternating first-person accounts in a stream of consciousness that brings to mind Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, A Short Tale of Shame is a beautifully written novel that relishes in symbolism and mythology. As he reflects on his relationship with his daughter, Krustev wonders, "What were these barriers that arose between you and those closest to you?" It is the question of the novel—and Igov suggests it is best answered outside of one's comfort zone, on the road.

—J.F.

Brilliant Blunders By Mario Livio

Even geniuses make mistakes in science—except some blunders turn out to be correct.

“A man of genius makes no mistakes,” Stephen Dedalus says in James Joyce’s Ulysses. “His errors are volitional and are the portals of discovery.” Livio, an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, doesn’t go that far, since many brilliant scientists were just dead wrong. The great Lord Kelvin used the latest science at the time—he didn’t just guess—and calculated that the sun was no more than 20 million years old. He was wrong (the sun is about 4.5 billion years old, about as old as the Earth), but he was wrong in an interesting way that led scientists to search for the existence of the source of solar power. (It’s thermonuclear fusion.) Albert Einstein thought that the universe must be stationary and added a “cosmological constant” to his original theory of general relativity. The universe, it turns out, expands, and Einstein considered the cosmological constant his “biggest blunder.” But observations today suggest that, indeed, the cosmological constant is necessary. Science must be continually improved upon, and blunders provide that drive through “the portals of discovery.”

—Jimmy So