Earlier this week, inside the Stonewall Inn for the very first time, the site of the landmark, much-storied riots of 1969, Tom Daley felt goosebumps.

“I thought, ‘Wow, this is such a historic place. If only these walls could talk,’” Daley, the Olympic gold, multi-championship and medal-winning out-gay diver, told The Daily Beast. “This place is the start and heart of modern gay liberation. It felt really amazing to be there. For me, it was this moment of…” Daley paused. “Gratitude was the big emotion for me, for everything that LGBTQ people who came before me have fought for and done. I love the fact it still exists, and we can go there.”

As New York life streamed by the Midtown coffee shop we met at, it was the present state of LGBTQ politics and equality that was exercising the 27-year-old—he turns 28 Saturday—athlete, TV presenter, and now self-described “twunk.” An untouched Junior’s cheesecake sat between us, a gift from ABC’s GMA, just one of Daley’s stops on a whirlwind 48-hour trip to promote the American publication of his memoir, Coming Up for Air (HarperCollins).

“There were so many hard bits when looking back through my life, like losing my dad, having to relive the experience of the 2016 Rio Olympics, where I thought diving might be over for me,” Daley told The Daily Beast. “Two words sum up my career: perseverance and resilience. I keep going and bounce back from injuries and anything else that happens.”

Soon, Daley would talk about grief, body image, knowing and valuing queer history, the joy of fatherhood, wanting more children, his love for husband Dustin Lance Black, contemplating retirement, being a sex object, and—of course—his fervent passion for knitting. But first he forcefully denounced the rise in transphobic and homophobic lawmaking in Britain and America, condemning the over 300 anti-LGBTQ bills originating from Republican-run legislatures—many focused on preventing trans teenagers from playing sports at school or accessing gender-affirming care. Daley also let rip on Boris Johnson’s U.K. government’s plan to outlaw conversion therapy—but only for LGB people, not trans people.

“It makes me feel really sad, quite honestly,” Daley said. “For so long you hear the argument people’s sexuality and gender identity should not be discussed at a young age. But then children see images of love stories between men and women. That’s pushing ‘sexuality’ and ‘gender identity’ on to kids, but it’s seen as acceptable. If it is two men kissing, it suddenly becomes hyper-sexualized in those politicians’ minds. For my generation growing up, a marriage was seen as between a man and woman. Now kids are being taught marriage can be between two people. That’s good, and something really powerful.”

Daley, who last week won an Outstanding Contribution to Sport Award at the Sports Industry Awards in London, strongly condemned anti-trans prejudice and lawmaking. “Imagine being unhappy in the body you’re in and feeling trapped in it. Listening to those trans people, and ensuring they have gender-affirming care, saves lives,” Daley said. “In certain states, there is an effort to take control of what people can and cannot be. I think everybody should be themselves completely and unapologetically themselves. It is what makes everybody unique and interesting, and can help us come together to create a beautiful and diverse world.”

Sports, Daley says, “should be the most inclusive place for all. Nobody should be discriminated against in sport. Of course there is a lot everybody needs to learn and understand the science. But at no point should trans people be banned or told they cannot do something they love to do. It’s amazing to win medals, but sports is about more than winning medals. It is about taking part in something you love alongside other people who feel the same. Let’s do it all together. I love sport, and I think everybody should have the opportunity to be involved in it.

“You’ve got states who won’t give young trans people gender-affirming care, and then you’ve got lawmakers and certain sports saying ‘You can’t play’ in this or that category. Trans people are being put in impossible situations. What happens if they can’t have gender-affirming care, and they can’t play sports? They’re constantly being pushed away and shut out. I feel extremely strongly people should be able to compete in the sports they love to do.”

Tom Daley and Matty Lee of Team Great Britain on day three of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games on July 26, 2021.

Davis Ramos/GettyDaley concedes that living in London is “such a bubble” but feels the U.K. is becoming “growingly divided, with every issue politicized.”

“Honestly, I think it’s wrong. It’s also gross,” Daley said of the U.K. ban on conversion therapy not being extended to trans people. “Does the government think we should accept it being banned for LGB people and not trans people? I think it’s really important the whole LGBTQ umbrella should come together and fight for trans folk. I don’t understand how people can be so vicious about minority groups when laws giving equality to those groups doesn’t affect them. Just allow people who are trans to live their best lives, be happy, and thrive.

“If we think those who make the laws are just going to come after trans people and leave it at that, it’s not going to stop there. Over here, the leaked Supreme Court opinion on abortion signals, to me, they will also come after marriage equality and other protections for queer people. It’s really important to not get complacent. That’s why visibility in sports and entertainment is so important.”

Daley also hailed the coming out of Jake Daniels of Blackpool, who this week became the only professional footballer in the U.K. currently playing who is openly gay.

“It’s just incredible,” Daley told The Daily Beast. “I think about what it means for any queer young kids growing up thinking now, ‘Maybe I do now have a space in football, maybe I will get in, maybe I will be welcomed.’ It’s not just that the queer community has been so celebratory of it, but the fact of seeing people like [English national team captain] Harry Kane speaking out about how amazing it is. Straight footballers at the top of the game are commending him, and I think for visibility in the sport it’s just incredible. Jake and [Australian professional footballer] Josh Cavallo are paving the way.

“The culture of football doesn’t seem like such a safe space to come out. The fact that Jake came out is a really powerful message to send. It’s so incredibly brave it might encourage people to be brave and more people to come out, able to be themselves. It will also make it safer for other athletes to do so as well. There is such power in visibility, and in telling or sharing your personal story. With me, I had people respond that they liked me before I came out, and what had really changed when I came out? Not much.”

The unanswered-question-as-yet is: How will the fans react when watching Daniels play. “Last year we saw at the European Championships how racist fans can be, and what they shout,” Daley said. “It’s as if, in that spectator ground, they’re empowered to say what they want. It’s because they feel in a safe place around like-minded people. It takes a shift in culture from the top down where the heads of organizations and governing bodies are creating that accepting and open culture because if it doesn’t start there, it’s never going to change.”

However, FIFA is holding the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, where homosexuality is illegal. The governing body has told hotels there to welcome guests in a “non-discriminatory manner.”

“It’s really difficult,” Daley said. “It’s one thing to guarantee the safety of LGBTQ people and athletes, but what about the people living there? For the longest time, I said such countries should be banned from holding events, but that just closes the door on them growing. Is there a way to make the countries have some kind of LGBTQ education as part of the sporting events, or to create a safe space for queer people to watch the event? For so many people in that country they may never have met an openly gay person. Just creating that visibility in those countries is so incredibly important. That goes for gender equality, racism, and disability too. Sport should be the most inclusive place for everyone, not just straight white cisgender men.”

“It’s a scary prospect, thinking about the future”

Daley began diving at 7, competed in his first championships at 9, and at 14 in 2008 was Britain’s youngest Olympic competitor. In 2009 Daley became Britain’s first individual diving world champion when he won the 10-meter platform event. The following year he won a double gold in the Commonwealth Games in the 10-meter platform and 10-meter synchro events. He is a five-time European champion, and four-time Commonwealth champion, and the first British diver to win four Olympic medals.

A moving portrait of his young life and road to astonishing success, his memoir is also a brutal catalogue of the physical injuries and strain his sport has subjected his body to.

“Your hand hits the water at 35 miles per hour,” Daley told The Daily Beast. “It takes 1.56 seconds to hit the water from the platform, and there is the impact of the body jumping on the platform, hitting the water, your back, shoulders, triceps… I broke my hand. I injured my shins, got pneumonia. There is always something that is going to get hurt. I got good at managing it later in my career, by not overtraining and managing what I did so I didn’t kill myself. Meditation, mindfulness, knitting, and Gyrotonics were game-changers.”

“Everything started shifting” after the birth of Robbie in 2018, Daley told The Daily Beast, “my perspective, priorities, the things I need to work on in order to have longevity in my career and not just training for the next competition.”

Tom Daley during a break from training for the 2016 Rio Olympic Games on Jan. 18, 2015, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Matthew Stockman/GettyDaley “hung up my trunks” after the Tokyo Olympics last year, where he won a gold medal in the men’s synchronized 10-meter platform. (He is also a double world champion in the 10 meter platform event.) Taking a year off, he has not been on a diving board since. Now he is contemplating his retirement, he reveals. The question seems to be when. “I am really conscious of it. I’m aware that for lots of athletes you get to the point of finishing and then it’s ‘Where next?’ It’s like starting from scratch almost. That’s why I do bits of TV and the knitting, so I have something to fall back on.”

The year off he’s taking will end in September, and he plans to make a final decision then. “I love diving, and at the end of the day I want to keep going on with that. I have to figure out what more I want from the sport, and it’s a big decision to take and it will change my life completely. I have been enjoying spending more time with family and doing things I have been putting off for a very long time.”

So, will he retire at 30?

“If I went to Paris [the 2024 Olympics] that would definitely be the last one, because any older than that your body really starts breaking down. I have to ask myself what events I will do: platform, synchro, or just springboard? There are lots of options. I have to figure out what’s best. It’s a scary prospect, thinking about the future. Diving has been a part of my life for such a long time.”

Daley says in the last few months he has not experienced “FOMO” (fear of missing out), but he is intrigued to see what he will feel watching while not taking part in the World Championships, European Championships, and Commonwealth Games. The year off and that seem like a dry run for retirement. “I don’t want to rush into any particular decisions. I might go back and see if it’s still something for me. I don’t want to put any pressure on myself, ‘This is the last ever dive I will do’—know what I mean?”

Fatherhood has changed Daley “hugely.” The Rio loss (he didn’t make the 10-meter platform final) was made bearable because he knew had the “complete love and support of my family. It takes so much pressure off. Being a parent is the best thing in the world. I miss Robbie terribly when I go away. I’m so excited to see him when I get home tomorrow. When I was saying goodbye to him it was 6.30 a.m., he was in bed and wouldn’t let go of my arm.”

Daley and Black are planning on having more children. “Lance and I always talked about having a big family, we just don’t know how big.”

Robbie turns 4 next month and starts school in September, and is “an adrenaline-seeker,” climbing and jumping everywhere. “He’s a full-on little boy now, not a baby or toddler. He’s my little buddy. We go to lunch and museums, he has his own opinions and thoughts.”

Tom Daley knitting before the Men’s 10m Platform Final on Day 15 of the Tokyo Olympic Games on Aug. 7, 2021.

Clive Rose/GettyIn the book, Daley writes about the homophobia he and Black received as a result of having a child by surrogacy. Such prejudice tends to ignore, says Daley, that “as same-sex parents you really have to want a kid. It’s not as simple as a bottle of wine and a good time. A lot of thought has to go into it.” He takes some heart, he says, by how sweet people are in person, and that the surrogate mother, whose anonymity they have safeguarded, “will always be part of our family. She’s wonderful. We gained a friend and a new family member. Robbie calls her his ‘tummy buddy.’”

As they want more children, Daley says he and Black have discussed with her the possibility of carrying more babies for them. “Once you have a relationship with someone that’s so special, it’s hard to imagine going down that route with someone else. It’s just with the Olympics and COVID it’s figuring out how and when to restart that process if we go down that route again.”

Becoming a father himself reminds Daley of how much parents sacrifice to help their children be their best. His own dad, Robert, he smiles, used to embarrass him in how volubly he would support him at swim meets. “But I was as proud as punch when Robbie said ‘papa’ for the first time, and I know I’ll feel the same when he finds other things that he’s passionate about.”

Rob Daley died aged 40 from cancer, having been diagnosed with a brain tumor in 2006. Tom’s grief over his beloved father’s death returns, he told The Daily Beast, at “big moments in my life where I think, ‘I wish he was here to see that.’ It’s not that grief gets smaller, you just learn to grow around it.”

He writes in the book about pushing that grief aside immediately after his dad’s death to focus on his sport. It was Black, Daley says, who encouraged him to speak about it. Now, he and Black discuss everything, and “it has been amazing to have trust. We’re each other’s safe place, and it’s really special. We have been together nine years and married for five. It’s nice to still feel that safety still.” (They also make very cute YouTube videos about the joys of coupledom, coffee cups in the sink, and who said “I love you” first.)

Daley was always worried he was “burdening” others with his concerns, and it has been liberating to discover that opening up has been so healthy—as well as Black, he also talks to a sports psychologist, which he knows is a privilege others do not have—but hopes others can find people to trust to share their thoughts and anxieties with.

The knitting started because his coach said Daley needed to find something to do at the Tokyo Olympics so he wasn’t “on the go all the time. I’m someone who can’t sit still. Lance suggested knitting squares as something people did on film sets to pass time.” At the Olympics (he still loves the cardigan he made there), it allowed him to say calm and focused. And now, he takes it everywhere with him whatever he is. Out of a bag he produces the bridal garter he is making for a friend that needs some elastic, flowers, and pearls to be completed. When his management asked what he would like to do after his diving career ended, his immediate answer—and it still stands—was “knitwear designer.”

“I thought, ‘I want to be me and stop hiding’”

Growing up gay in Plymouth in the southwest of England, Daley first heard the word at secondary school, and thought, “Oh that’s what I am.”

As his diving career took off, he was the subject of vicious bullying. He dated girls but, already the subject of public scrutiny, didn’t feel able to explore being gay “because I was so terrified of getting caught or being outed,” he told The Daily Beast. “I imagine, if I hadn’t been been gay, that I would have come out earlier. My whole life was very public-facing. You never knew if someone was going to throw you under the bus.

“It wasn’t till I met Lance that I felt safe to say, ‘You know what? This is me.’ It was terrifying. My then-management was telling me I would lose my sponsorships, and what would happen if I was competing in a country that wouldn’t accept me. Dad had died, I was supporting my family. I got to a point where I thought, ‘I can’t deal with any of these questions. I want to be me and stop hiding.’”

The 2013 video he made to come out—viewed now over 13 million times—was, Daley says, the best way of saying what he wanted to say without anyone twisting his words or asking follow-up questions.

“I didn’t think anything of it, or that anyone would care in way they did. I got messages saying it had helped kids start a conversation with their own parents, who were like, ‘We love Tom, that hasn’t changed,’ and that helped them understand and accept their own child.”

Tom Daley and Matty Lee of Team Great Britain pose for photographers with their gold medals after winning the Men’s Synchronized 10m Platform Final on July 26, 2021, in Tokyo.

Clive Rose/GettyAs he has grown up, Daley has also pondered becoming a pinup and sex object, and the anxieties over his body that led to an eating disorder. For him, his diving trunks are a work uniform, but he knows for others his body is something else. “I was doing photoshoots at 15, 16, half-naked. Looking back, it was quite sexualized,” he told The Daily Beast. He still does those shoots, and still looks amazing. “But I never looked at my own body in that way until 2011, when my diving performance director told me I needed to lose weight,” Daley said.

“All of a sudden, my body wasn’t just a performance tool, I saw it as something people were looking at to see how much fat was on me. My whole relationship with my body changed in that moment. I struggled with eating and body image issues. I didn’t want to burden people, because they would look at my body and say, ‘It’s fine, what are you talking about?’

“You know it’s irrational, but you can’t help but think what you’re thinking. I still struggle with it now, especially with not diving for a year. I feel I am constantly learning about my body, my relationship with it, and what I can and can’t do to feel happy. And I have become far happier in my own skin since accepting we’re human beings and can only do our best with what we’ve got.”

Tom Daley at the Met Gala on Sept. 13, 2021.

Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic/GettyDaley emphasizes he feels he has a healthier relationship with his body now. “There are periods of time when I am on holiday where I eat what I want to eat, and periods of time when I’m on a health kick. It ebbs and flows, and I think everyone has a similar relationship with their body.” He looks at the cheesecake in front of us. “There was a period in my life where I wouldn’t touch that. Not now. So that’s progress. It’s about seeing things in terms of moderation and balance.

“There are all kinds of pressures being an athlete in the public eye, and a gay athlete in the public eye, and figuring out what the balance is. You’ll never meet an athlete who is completely happy with their body. They are always looking at someone else’s body for inspiration or to strive towards. It’s about what’s best for you and not sacrificing your mental health to lose half a percent of body fat.”

His youth, diving skills, and coming out have also made him a celebrity. Last year, he was invited to the Met Gala. “It was so surreal,” he says, noting that the standout moment was being in the toilets, Troye Sivan in a dress needing to pee, Rihanna standing in the doorway suggesting Daley take a picture of it, then Shawn Mendes walking in and asking what the hell was going on. Daley’s reply: “I don’t know, but here we are.” The partying concluded at around 3:30 a.m., “which is quite early for New York, right?” Daley said.

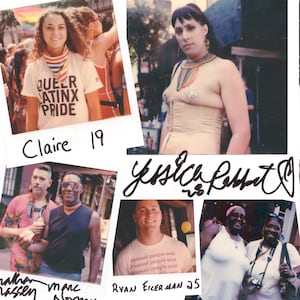

Tom Daley at a book signing for “Coming Up for Air” at The New York LGBT Community Center on May 18 in New York City.

Bruce Glikas/GettyDaley also just found out what a “twunk” is, and why he apparently is one.

“I thought it was the past tense of ‘twink,’” he says, smiling, “as in a past twink, an aging twink [‘twink’ being the word for a cute, younger gay man]. I was like, ‘Does that mean I am old now?’ and I was told, ‘No, it means muscly older twink.’” Is he embracing that label then? “I guess so. I am so out of the loop on all the groupings: otters, bears, twinks. I do find it funny that as a minority community we always find ways to divide ourselves into more minorities.”

Daley said getting older and becoming a parent meant the pressures of being a role model had lessened. “Sometimes you want to just be out with your friends and be silly. In this age of social media and phones, you have to be mindful. At the end of the day, I’m me, and if people don’t like it they can lump it.”

His memoir makes clear his small group of friends and family (including his mom, Debra) have always been his most valued support. He recalls that his parents just cheered him when he was younger and were not, like other parents, hawkishly pushing him to train harder or do better. “Every time I looked at them, they’d smile at me or wave. Everything they did came from a place of love rather than expecting me to do anything. As athletes grow up, it doesn’t matter what their parents say. If the athlete is going to get to the top of their game it’s already in them. It’s nature and nurture. Nature is attitude, the nurture is the skills you learn.”

Contemplating aging, Daley says, “I always feel like I have always been older than I am. I also thinking aging is a beautiful process that shouldn’t be interrupted. Getting older also means getting wiser and more life experience. In terms of how I look, I don’t care. I am married and have a kid. I do what I do keep young, with exercising and a skincare routine. That makes me feel good.” Would he have Botox or plastic surgery? He laughed. “Nothing like that, oh God no! I can move my face still,” he laughed.

Because he has been in the public eye so long, “a lot of people say, ‘I remember you when you did this.’ A lot of people know more about my life than I do, which is odd. This creates quite a sweet way of how they talk to me like I’m their little brother or kid. People come up to me as if they know me really well. I never know if I know them, so I always say, ‘Hi, good to see you.’ People are super sweet, especially when I go home to Plymouth.”

“There’s no one-size-fits-all when it comes to coming out”

Meeting Black in Los Angeles in 2013 at a friend’s dinner was “literally love at first sight. I know it sounds cheesy, but we broke all the dating rules. Within the first week, we said we would get married, that we loved each other, that we were boyfriends, and named our future children!” Nearly a decade on, they’re still “old romantics at heart” who like to organize cute surprises for each other. Black, who won an Oscar for his screenplay of the biopic Milk about the history-making and iconic San Francisco politician Harvey Milk, also introduced Daley to the fascinating terrain of queer history.

Dustin Lance Black and Tom Daley at the premiere of FX’s “Under the Banner of Heaven” at Hollywood Athletic Club on April 20.

Axelle/Bauer-Griffin/FilmMagic/Getty“People my age and younger are guilty of not knowing queer history and not understanding the rights and liberties they now have and where they came from,” Daley says. “It was a big eye-opener for me. I was very ignorant of that for the longest time. Reading and learning about queer history makes you realize we haven’t had the rights we now have for that long. There are still countries where LGBTQ people face criminalization and persecution and attacks. It made me realize I had to use my platform as best I could to create change and bring voices to the table who otherwise would not have been able to.

“With Pride month coming up, it’s really important for younger people to understand why and how the parades originated. I do think every Pride event needs an educational aspect and not just be a commercial opportunity. It’s great that these events are fun and joy, but these parades first came out of necessity—out of LGBTQ people insisting they had a right to exist. We still have to fight for our rights. It’s that age-old thing: Always remember where you came from.”

People call Daley brave. Did he feel it? “I was terrified when I came out. I felt like I had to be brave, to press the button. So many other people are braver than I ever had to be, people who are out and existing in countries where their lives are at risk. That’s where true bravery lies. I had the support of my family. Others may be coming from a religious background, which means coming out takes an extraordinary amount of bravery.”

On whether more people like him in the public eye should come out, Daley said, “People can only come out when they feel ready. You can’t force people to come out if they don’t want to.” Closeted famous people have said to Daley, he says, “I wish I could be as brave as you.” But, he says, “I don’t feel brave. I just say everyone has to do their thing in their own time—there’s no one-size-fits-all when it comes to coming out.”

Daley says he receives messages on Instagram from all over the world that he has helped people to come out, or be themselves. “I had no idea I could have an impact like that on anyone. It’s overwhelming and very surreal. When you’re just living your life, you don’t think about the impact you have on other people in that way. I had people say there were times when they wanted to take their own life and then had seen people like me come out and share their story, which made them feel that they do have a place in this world. That is very special. But again, that is not just down to me—that’s as a result of a collective of the queer community being visible.”

It was time to head to an event at the LGBT Center, and off Tom Daley sauntered into the sunshine, cheesecake in hand.