Rare is the play that has an artfully designed interval, indeed a necessary, exciting thud of an interval. Plays—and their expectations of audiences’ posterior comfort and attention spans—are so scattered these days. We are getting used to sitting past the usual 90- to 100-minute mark, towards two hours and sometimes more.

Suzan-Lori Parks’ Topdog/Underdog (Golden Theatre, to January 15), directed by Kenny Leon, is a brilliant, electrifying piece of theater for many reasons. One of those is, at around two hoursm 15minutes, while it could reasonably expect its audiences to sit for its duration, its structure imposes an interval at the best moment. Bam, lights out, and that happy buzz of an audience who can’t wait to swap notes, take a bathroom break, get a drink—and then get straight back to their seats to see how it all works out.

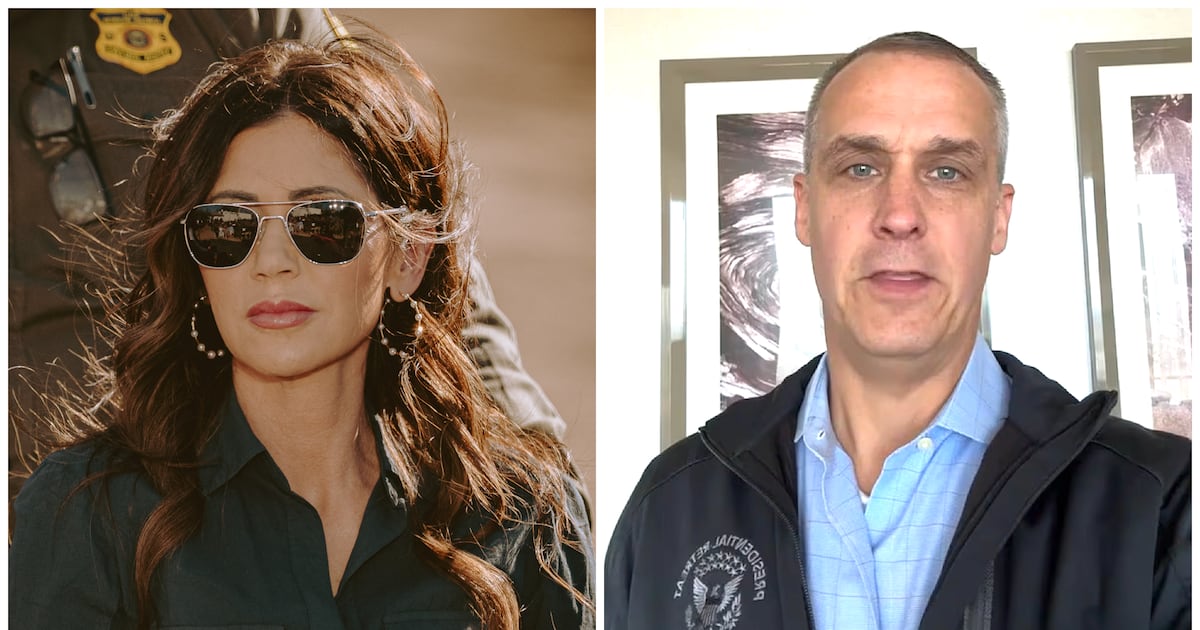

This is the 20th anniversary production of Topdog/Underdog. Parks became the first African American woman to receive the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for the play in 2002, in which two brothers, the younger Booth (Emmy-winning Watchmen star Yahya Abdul-Mateen) and the older Lincoln (Tony and Emmy-nominated Corey Hawkins), abandoned by their parents when children, now find themselves as adults bound together by the contradictory, attracting and repelling, forces of love, resentment, loyalty, and mistrust.

The writing and direction are scythe-sharp and precise, and Hawkins’ and Abdul-Mateen’s are two superlative performances—for this critic, the standout of this current Broadway season so far: energetic, witty, mischievous, searing, tender, and vulnerable.

All we see of the men—bantering, being sweet, bickering, planning, dreaming, interrogating, infuriating, pacifying, angering—is in the room, with its one bed. They are Waiting for Godot’s Vladimir and Estragon, who want something to change—money to escape poverty, ambition to vault them somewhere new—who possibly want to say goodbye to one another, who are desperate to be somewhere else, who want to leave through that door. Yet they remain yoked together, unable to separate, unable to bid farewell.

Lincoln is defined by Parks in her script as the topdog, Booth the underdog. They are meaningfully named after both the iconic assassin and the iconic president. The title of the play is the dynamic we see before us. Two men, blood-tied but needling opposites, flipsides of a shared trauma they know all too well. As well as painful memories of times past, and a determination to surmount them and the racism of the world outside these doors, there is a jockeying for position going on—who can be successful, who will find love (Lincoln has left his wife, Booth has fallen for a woman named Grace), who is up on their luck, and who will be fatefully down on his.

Lincoln in the play is a President Lincoln impersonator, who puts whitener on his face, and a big stovepipe hat, and a fake beard (the on-point costumes are by Dede Ayite). Hawkins is a master of many things, one of them being the physical comedy to illustrate how he really feels he is animating his act at the moment of his subject’s assassination. He shows Booth how he can go straight down, he can go down with a flourish, and he can go down with his limbs in jangling dis-concert.

Lincoln and Booth both know the irony of a Black man dressing up as the “Great Emancipator” in the service of breadline work today. This is honest work, Lincoln insists. Booth replies: “Dressing up like some crackerass white man, some dead president, and letting people shoot at you sounds like a hustle to me.”

Booth in the play wants to emulate his brother’s card-sharp skills, especially at Three-Card Monte. He wants them to take the profit-making trick out to the streets as a duo, but his idolization is underscored by anger. If he is relatively plodding at cards, Booth excels at shoplifting—and we watch him dress, piece by piece, in that day’s swiped clothing. (He looks exceptionally fine.)

Arnulfo Maldonado’s gorgeous design is the play’s omniscient third character—its two swooping and soaring layers of ruched, luxuriant drapery beyond the walls of the men’s apartment can be seen maybe to illustrate the interior of Ford’s Theatre in 1865, when the historic Booth killed Lincoln; it also encompasses the performance of the two men we are watching, both in the world today around them, and in this room around each other. All the world’s a stage for the two brothers—including in the close quarters where they live.

Outside in the world, the brothers try to forge their own luck and futures, despite—pun intended—the cards they have been handed. Inside the scuzzy apartment, all their efforts seem to bubble to nothing, but the deep and binding knowledge they share of each other.

They share, they laugh, they jibe; other demons and bitterness threaten to poison their closeness, not least that Booth once slept with Lincoln’s estranged wife. The confinement of the apartment, the sudden downturn in fortunes, both men’s simmering frustrations point to tragedy—and sure enough, spurred by the deck of cards and the bigger themes the play contains, that tragedy comes suddenly. Your mind swings back to the title of the play, the men’s historical namesakes, fate, contemporary social forces, and personal circumstance. It is time, inevitably, for the curtain to come down.