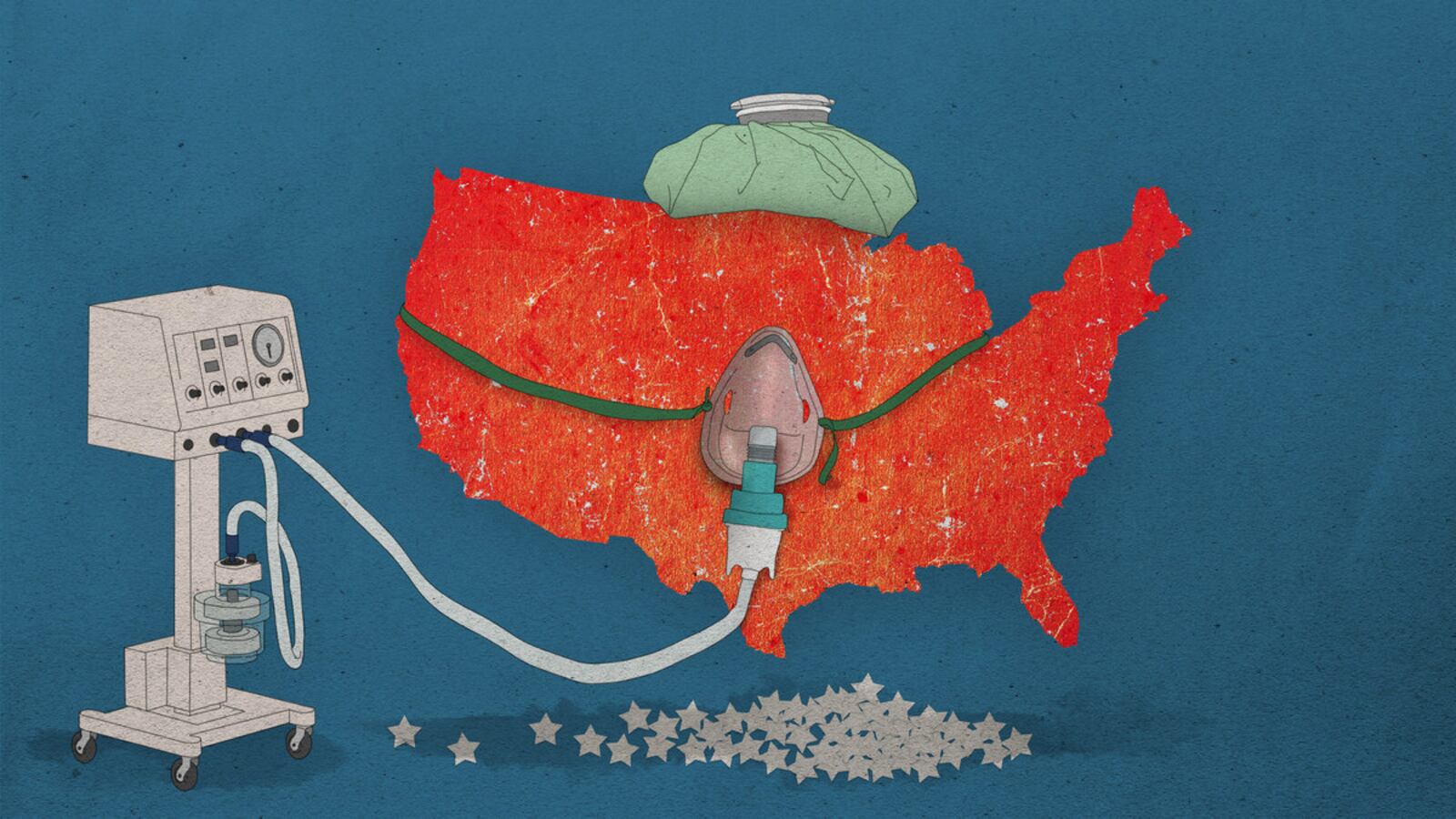

After weeks of resisting pleas from governors and healthcare workers to force private companies to ramp up production of medical supplies to help combat the coronavirus crisis, President Donald Trump on Friday afternoon announced that he had changed his mind.

In a public announcement the White House said that President Trump had written a memo to the Department of Health and Human Services directing secretary Alex Azar to “use any and all authority available under the Defense Production Act to require General Motors to accept, perform, and prioritize Federal contracts for ventilators.”

The news came after a confusing morning in the White House where officials were caught off guard by Trump’s mysterious tweets where he demanded General Motors and Ford to make ventilators and hinted that he may use the Defense Production Act (DPA) to enforce his requests.

Three senior Trump administration officials who have worked on these matters each independently told The Daily Beast that they were befuddled by the Friday tweets, and did not know what the president’s posts actually meant. Each official said that they were, at the time, still trying to get clarity from Trump or other senior officials on what, if anything, new had just been decreed.

Shortly after the tweet rant ended, White House officials told The Daily Beast that the president had yet to implement the DPA—a law that allows him to demand private companies ramp up domestic production of supplies—and that he was still relying on volunteers to come forward and help with production. Hours later, officials said Trump had decided to finally implement the DPA over the course of the day.

Trump’s mixed messaging raises additional questions about why the process for addressing dire hospital needs has been so disjointed more than 60 days after senior Trump administration officials were first warned that the new coronavirus would spread across the United States.

Trump’s tweet on Friday came amid renewed criticism from state governors—chief among them Andrew Cuomo of New York—who have begged him to use the DPA to help fill the needs for, among other things, additional ventilators. For the last week, doctors and nurses from New York City have posted harrowing accounts of mass shortages of personal protective equipment affecting their ability to save lives. Nurses from Mount Sinai, for example, posted a picture of themselves using trash bags instead of medical gowns.

But Trump has stressed that the private sector was doing enough to meet demand. On Thursday night, he went further, saying it was his belief that the request for ventilators from Cuomo was overstated.

That posture appeared to change by the next morning, when the president admonished General Motors and Ford for not ramping up ventilator production. He demanded that GM utilize a plant in Lordstown that it had sold last November to do so. And then said he would “Invoke ‘P’”. Only later did he clarify that “Invoke “P” means Defense Production Act!”

Those who’d been with the president on Thursday said he had grown enraged at General Motors for what he perceived to be a reneged deal, in which they were to have produced ventilators for states in crisis to use. The assumption was that Trump was merely letting off steam on Twitter as he absorbed the critical media coverage of that collapsed deal, which was first reported by The New York Times. Later on Friday, GM said it would be making ventilators but not at the plant Trump had suggested.

Trump has threatened to use the DPA before, only to not follow through. And he has been egged on in resisting to do so by a group of advisers who see in the coronavirus outbreak an opportunity to strengthen U.S. manufacturing and medical supply lines.

Chief among those aides is White House trade adviser Peter Navarro, who officials say is one of the people leading the White House’s response to demands that the federal government do more to help states fight the coronavirus.

“The DPA is standing at the ready, providing us quiet leverage,” Navarro told The Daily Beast on Thursday. “We’re getting tremendous cooperation from private enterprise, and if and when we need it for any reason whatsoever, we won’t hesitate to use it.”

Navarro’s position has confounded medical professionals, who warn that the current situation presents a dire crisis that the federal government must address. They and governors across the country continue to warn that relying on private companies could take weeks or even months to produce things like N95 respirators and ventilators at the scale necessary to put a dent in the virus’ spread. Deborah Birx, the coronavirus task force coordinator, said Thursday that there was enough equipment to go around and that states could share. But health officials in hot spot states such as New York are panicking. In the past 24 hours, 7,300 people in the state have tested positive for the virus. One hundred thirty-four people died in that same time period.

That’s left New York searching desperately for ways to maximize the scant resources at the state’s disposal. On Thursday, Cuomo approved measures to “split” ventilators in the state’s hospitals so that each one can serve multiple patients simultaneously.

Experts have been blunt in assessing the damage: were it not for the president’s insistence on not using the DPA, they say, additional lives might have been saved.

“In times of crisis, especially when lives are at stake, lawyers and policymakers are supposed to find solutions to problems, not create obstacles to saving lives,” said James Baker, a former legal adviser to the National Security Council. “There are solutions here.”

Global medical pandemics can prove difficult for massive bureaucracies to tackle. But the Trump administration’s response to coronavirus has been described as uniquely rocky. Officials say that the interagency process—where agencies are supposed to work together to respond to a problem— failed in the early days of the administration’s response, because there was a fundamental lack of understanding of how to coordinate around a pandemic.

“The whole-of-government approach that everyone keeps talking about really wasn’t happening in the early days,” one senior official working with the coronavirus task force said.

Even absent any official orders under the DPA, the measure can theoretically be used as an unspoken threat against companies that do not fall in line and lend their expertise and capacity to administration efforts to ramp up national production. The prospect of such aggressive federal intervention, the thinking goes, might be enough to spur private industry into action.

But the reliance on industry to make and distribute desperately needed supplies makes it difficult to determine whether those private manufacturers are on pace to meet the unprecedented demand for needed medical products.

“If the DPA was intended for anything, it was for this moment. Fifty states under operational stress, and we have a statute that actually cures that demand,” said Juliette Kayyem, a former assistant secretary of the Department of Homeland Security. “There’s clearly a cog in the system… I’m fearing it’s a philosophy.”

Even as the White House insists that it has a firm grasp of the country’s ventilator needs, it’s clear that the administration is still grappling with how to go about solving the shortage problem. Federal procurement records tell a story of a slapdash and not particularly overwhelming response effort. There are sporadic purchases of personal protection equipment, various forms of coronavirus tests, and acquisitions of medical supplies such as ventilators over the last few weeks. Illinois industrial supply firm W.W. Grainger has provided the Department of Health and Human Services with more than $1.2 million in laboratory coveralls, hoods, and sleeves. The company 3M landed a contract worth nearly $5 million this week to provide HHS with N95 respirator masks. Laboratory firm Qiagen is working on a $600,000 HHS contract, awarded earlier this month, to develop coronavirus tests.

HHS is even paying North Carolina pharmaceutical company PPD to develop treatment options using chloroquine, a malaria drug that Trump has suggested—and some medical experts have disputed—could be a silver bullet for coronavirus treatment. Chloroquine is currently available to a limited number of patients under Food and Drug Administration guidelines known as “compassionate use,” which allow patients facing life-threatening conditions to gain access to some experimental treatments.

But the bulk of federal procurement data indicate efforts to stock up on medical supplies for use by federal agencies themselves. Those agencies have scrambled for the necessary goods to disinfect workspaces and protect federal employees from transmission. The General Services Administration, the federal government’s logistics agency, has reported scores of purchases of respirators and face masks. Federal prisons have placed five-figure orders for toilet paper and hand sanitizer. The Department of Veterans Affairs has lodged a host of “emergency” purchase orders for medical centers around the country that find themselves dealing with or preparing for a huge influx of coronavirus patients.

Federal records indicate that VA facilities in New York have been particularly hard hit. On Tuesday, the Veterans Health Administration, which oversees the department’s health care system, lodged a $316,000 purchase order with medical device company Hill-Rom for “emergency ICU beds… due to COVID-19 crisis” for VA medical centers in Manhattan and Brooklyn.

It was one of at least 15 VHA purchases related to the coronavirus outbreak over the past two weeks labeled as an “emergency” order in federal procurement records.

Three officials working with the administration’s coronavirus task force described the internal conversations about procuring much-needed medical supplies and equipment as uncoordinated and chaotic. One official said just two weeks ago that the representatives from various agencies were still trying to figure out who among them had the responsibility to collect data on what kinds of supplies were needed where. Others were confused about how the administration should or could go about procuring those supplies.

The Daily Beast previously reported that on an interagency call about the supply chain breakdown during the coronavirus outbreak, a representative from the National Security Council said their team was collecting data on hand sanitizer shortages from press reports.

The situation was confused even more when the president announced that he had signed the Defense Production Act and then backed away from its implementation, sources said.

It wasn’t until last week that the Federal Emergency Management Agency took the lead on the government’s response on behalf of the Department of Health and Human Services that officials began to more fully understand how best to respond to the crisis..

Although FEMA is not used to organizing large-scale responses to pandemics, it does have well-established coordinating mechanisms that help the federal government facilitate the transfer of supplies to states and regions across the country.

“Crisis management has two parts—you have the brain, which is the policy side, and then the muscle, where the agencies are. This administration is doing neither but is owning both, and that’s where the confusion is,” said Kayyem. “FEMA knows what assets exist in the federal government and possibly in the private sector. And it knows how to deliver those federal assets to the states. This is not rocket science. This is basic demand, supply, get the chain moving.”

UPDATE: This story has been updated with additional reporting.