Muhammad Ali had trained little for his first fight against Leon Spinks in 1978 and had been so uncharacteristically silent and sulky in the weeks leading up to it that one headline dubbed the bout “Spinks vs. the Sphinx.” There were rumors of a split in Ali’s camp and problems in his relationship with the Nation of Islam. He also seemed to feel embarrassed about taking on a boxer who’d been in only seven bouts, as if it were beneath him.

Whatever the truth, vestiges of the cheerful old Ali reappeared in the months after that loss as he prepared, at age 36, to become the first heavyweight to win the title for the third time in a rematch with Spinks.

I visited Ali several times that summer, as I had the previous few years, at his rustic training camp deep in the woods of Deer Lake, Pa., driving two hours from New York and always playing on the way Paul Simon’s song, “The Boxer,” to get in the mood:

In the clearing stands a boxer,

And a fighter by his trade

And he carries the reminders

Of ev'ry glove that laid him down

And cut him till he cried out

In his anger and his shame,

‘I am leaving, I am leaving.’

But the fighter still remains.

Ali had no intention of leaving the ring before winning back the title and banking one last big payday, he thought at the time, at the rematch set for the Superdome in New Orleans on Sept. 15. But he had little else in common with the boxer in the song. He’d suffered few cuts, had no anger or shame, and had been laid down by gloves only a couple of times in his long career. His mind was still sharp but I could see that his thicker body and slower legs did carry reminders of every glove that had been laid on him over the years.

Ali lived in a modest log cabin with a king-sized, four-poster bed, sometimes lying there propped up on his pillows while writers gathered round with notebooks and tape recorders, a king holding court in his private quarters. He trained in a ring inside another log cabin with a separate room where his Cuban masseur, and quiet, dignified motivator and cornerman, Luis Sarria worked on his body. Ali spoke softly, almost in a whisper, with me several times while Sarria massaged him slowly. Ali ate next door in a log cabin dining hall where his Aunt Coretta, his mother Odessa, or his faithful cook Lana Shabazz prepared the meals for everyone according to Islamic dietary laws – no bacon, ham, pork chops or sausages – and variations of their own Southern recipes. Though some cynics doubted his devotion to Islam when he joined the Nation, or the Black Muslims, as they came to be called, and declared himself a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, Ali prayed three times a day in a small white-painted plank mosque with a Persian carpet on the floor.

There were log cabins for sparring partners, trainer Angelo Dundee and others in his entourage, as well as guests. Elvis Presley once stayed there and Sylvester Stallone wrote parts of “Rocky” there, basing the brash champion Apollo Creed on Ali. Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr. and Andy Warhol had come to the camp, along with other celebrities and thousands of fans. I took photographs of the log cabins and the boulders that Ali’s father, Cassius Clay Sr., had painted vividly with the names of boxing greats: Jack Johnson, Rocky Marciano, Joe Louis, Jack Dempsey, Gene Tunney, Jersey Joe Walcott, Sugar Ray Robinson, Archie Moore, Willie Pep, Kid Gavilan, Rocky Graziano, as well as those Ali had fought, Liston, Frazier, Foreman, Jerry Quarry and Floyd Patterson.

I photographed Dundee standing next to his own boulder and took another photo of Ali with a flyswatter in his right hand outside his log cabin gym, his eyes on a boxed videotape of a fight in the fingers of both hands, and his adorable eight-month-old daughter Laila, who grew up to be a boxing champion herself, on his lap.

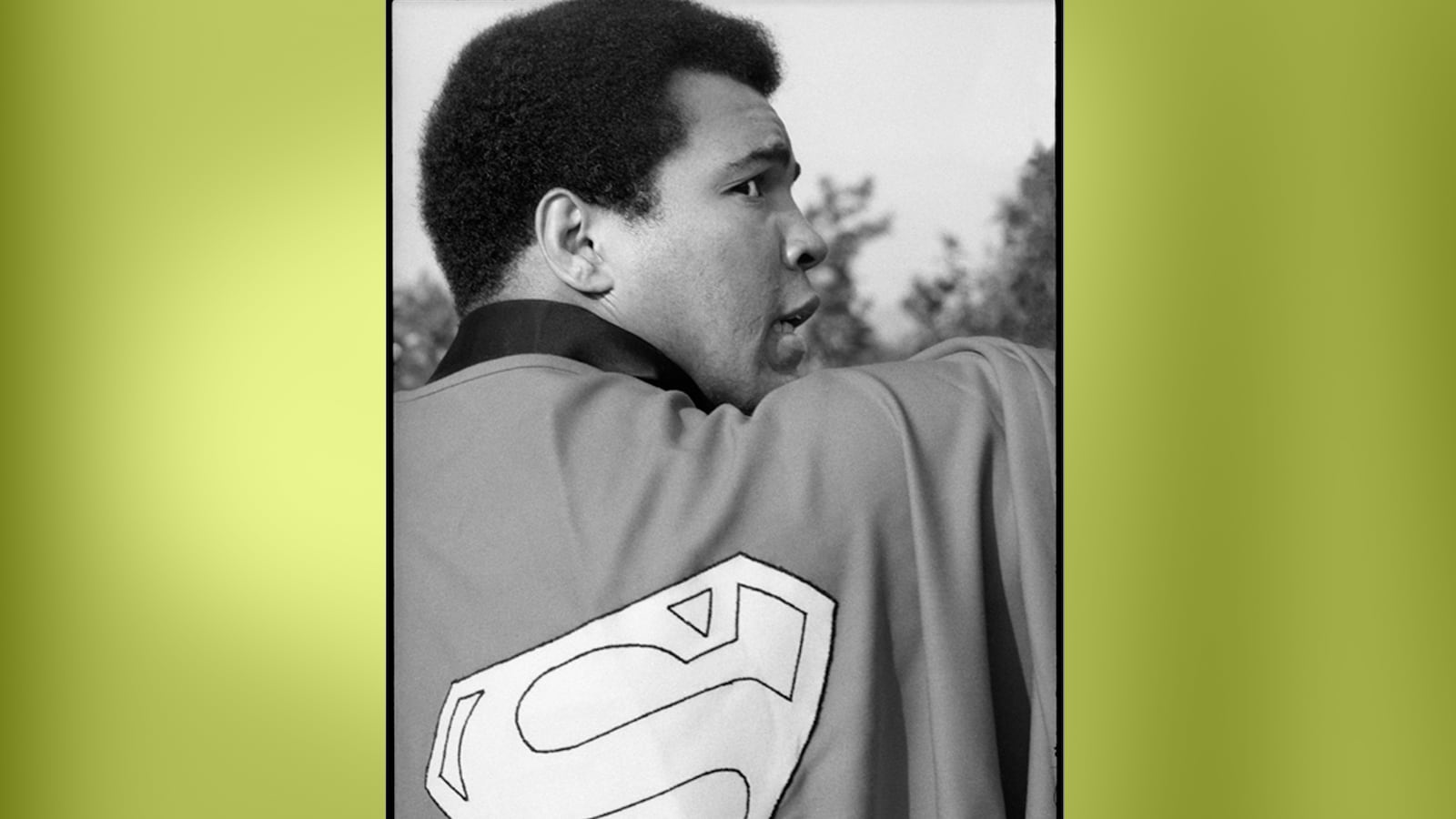

On one visit, executives from Warner Bros. and its subsidiary, DC Comics, showed up to sign a deal for the oversized “Superman vs. Ali” comic book they planned as a tie-in with the 1978 “Superman” movie, starring Christopher Reeve, in the works. The executives gave Ali a Superman cape. I asked Ali to put it on and pretend he was flying for a photograph. Dressed in black shoes, slacks and sports shirt, he climbed up on one of the boulders on the side of a hill, his arms outstretched as if he were about to leap tall buildings at a single bound. While he was up there and I was shooting photos, Dundee yelled at him, “Get off there, you idiot. You’ll break your neck.” Before he stepped down, I caught one wonderful image that I sent to him and have sold at galleries: a tight shot of Ali’s face turned slightly in profile and the cape with the big Superman symbol draped across his back. In that one image, the greatest fictional superhero and the greatest real life superstar of the past century merged.

Shortly before the Spinks fight, I drove again to Ali’s camp, this time with my girlfriend, soon to be my wife, Cynthia. While I interviewed Ali for an exclusive, one-on-one feature I had set up, she would hold a tape recorder microphone for a UPI radio piece. Cynthia and I met when she was a children’s television producer and writer for the PBS affiliate in Hartford, Conn., and had been living together in Soho for nearly five years. She had become UNICEF’s worldwide communications officer, based at the U.N. in New York, and didn’t know a thing about sports. That didn’t stop her from going with me to several events and helping out – the Montreal Olympics, the U.S. Open tennis, Wimbledon and a couple of Muhammad Ali fights.

Herbert Muhammad, Ali’s manager and a son of Black Muslim leader Elijah Muhammad, took a liking to Cynthia at one fight because she happened to be wearing a thin belt with a golden star and crescent on the buckle, like the Islamic symbol. They chatted at poolside in Las Vegas while I was doing an interview with someone else and he told her about a deal he was working on for Ali’s next fight. I confirmed it and got a nice break on the story.

Now at Ali’s training camp, Cynthia walked into Ali’s log cabin with me and blushed as she saw Ali lying on his bed totally naked except for a white towel over his private parts. Trying to keep her composure, she set up the big radio recorder at the foot of the bed while I stood at Ali’s side with my notepad and smaller tape recorder and asked questions. Somehow at the end of the interview, while she was putting the microphone away, she got the cord tangled up in Ali’s jockstrap hanging on one of the bedposts. As she struggled with the cord and the jockstrap, her face turned two shades redder and Ali laughed hysterically, his belly jiggling and the towel nearly falling off. That pretty much made his day.

“I tell you what I’m going to do, little lady,” he said to her when she finally untangled the microphone and jockstrap. “I’m going to give you two interviews, one if I lose and the other if I win.

“If I lose,” he said, lowering his voice to a soft, woeful tone, “oh, I was terrible, I’m finished, my championship gone, don’t have no power left, my legs are too slow, got no punch, got nothing. Ali’s too old. He ain’t the greatest no more.”

He paused, his face brightening.

“If I win,” he said, raising his voice to the familiar sound of the Louisville Lip in his prime, “I am still the greatest of all times. I’m still pretty. I got my legs back. I can dance again. I still float like a butterfly and sting like a bee, don’t let nobody tell you I ain’t the same Ali.”