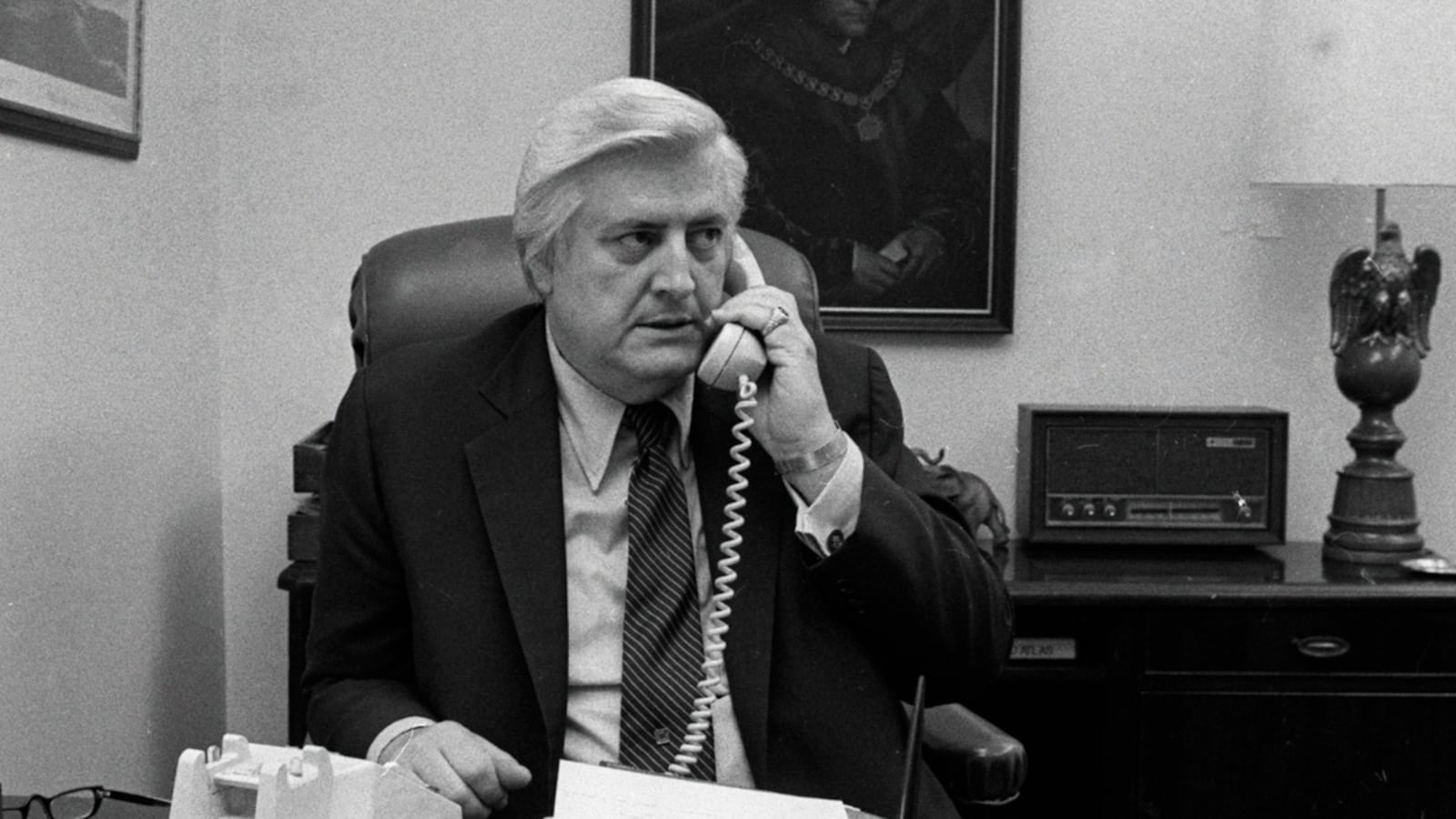

Earlier this year, when an all-male congressional panel debated whether employer health plans should have to cover birth control and Rush Limbaugh lambasted law student Sandra Fluke for arguing that they should, many people were left asking, “When did birth control become controversial?” In some ways, we can thank former Rep. Henry Hyde (R.-Ill.) for setting us on this path.

The attacks on contraceptive coverage can be traced back to an amendment of his that turns 36 years old today. The Hyde Amendment prohibits coverage for abortion in the Medicaid health-insurance program for the poor in all but the most limited circumstances. This law restricts insurance coverage for reproductive health care—just as conservatives are now seeking to do with birth control—and it has been justified by the argument that those who oppose something shouldn’t have to subsidize it. It’s the same argument being advanced to suggest that employers shouldn’t have to cover contraception in their employee health plans.

It is always easiest to go after the rights of the most vulnerable first. Hyde himself admitted, “I certainly would like to prevent, if I could legally, anybody having an abortion, a rich woman, a middle-class woman, or a poor woman. Unfortunately, the only vehicle available is the…Medicaid bill.”

A woman who cannot afford to pay for an abortion must raise the money somehow, often by putting off paying rent or utility bills, begging and borrowing from friends and family, and pawning dear or necessary items. Some women end up continuing the pregnancy against their better judgment or taking drastic steps to end the pregnancy themselves.

We should care about the rights of the disenfranchised first and foremost because it is the moral thing to do, but we must also be vigilant of their rights in order to safeguard our own. As the recent debate over the 47 percent who don’t pay income taxes revealed, we all rely on assistance from the government one way or another, at one time or another. If we allow politicians to shred the safety net for our neighbor, it might not be there for us when we need it.

That is what is happening with abortion coverage and what may happen with birth control if we are not careful. Once the Supreme Court upheld the Hyde Amendment in Harris v. McRae in 1980, four years after its original passage, abortion opponents saw their opening. Over time, they passed a number of copycat laws that now restrict abortion coverage for federal employees, the military, federal prisoners, immigrant detainees, Native Americans, the Peace Corps, and many more.

Then, during the health-reform debate in Congress, we saw social conservatives embark on the last frontier of restricting abortion coverage—banning it in private health-insurance plans. Although they were not successful, they have not stopped trying. In the current session alone, they have introduced at least five bills that involve “taxpayer funding” of abortion, four of which regulate the private insurance market.

And while they continue to try to eradicate abortion coverage, they have moved on to birth control—and again they started with the poor. First, they attacked federal funding for family-planning services, almost shutting the government down over grants to Planned Parenthood, and then they worked their way up to private coverage in employer-sponsored health plans.

Religious employers, they say, should not have to include contraceptive coverage in the health-insurance plans they provide to their employees. However, failed legislation in the Senate would have allowed any boss, including a for-profit company, to deny coverage for any health-care service, not just birth control. It raises the question: when they are done with abortion and contraception, what health-care need will they target next?

The attacks on birth control may be relatively new, but the strategy is decades old. We should learn from our history and reject all political efforts to influence a woman’s personal health decisions by withholding insurance coverage for the care she needs.