These are vexing days for Venezuelans. For the past 14 years, a single, charismatic leader, Hugo Chávez Frías, has dominated public life, occupying the airwaves, holding forth on stage for hours at a time, and crisscrossing the country as if on an endless campaign. Now suddenly this country of 29 million has had little but silence and anxious speculation.

Since Dec. 10, when Chávez was flown to Havana for yet another round of emergency surgery—to treat the cancer he claimed to have beaten—the man who lorded over every aspect of national life has not been seen nor heard from. Reelected convincingly last October, Chávez failed to show at his own inauguration in Caracas on Jan. 10, launching the country into an unscripted political transition where intrigue, improvisation, and conspiracy theories trump the Constitution, transparency, and due process.

The uncertainty has ratcheted up tensions in this hyperpoliticized country and kept Chávez’s minders shuttling to Havana and back, ostensibly to call on the leader whom they claim is “waging a battle with death,” but also, in all likelihood, to hash out the country’s clouded future far from the prying eyes and ears of the Venezuelans and the international press.

At home, opponents of Chávez’s ruling United Socialist Party have grown more strident. The opposition front, MUD, is reportedly organizing a massive march to force the government to come clean on the health of the stricken leader and to toe the legally charted path to transition. “Stand up and speak to Venezuela, and say what is happening in the government, because Venezuela is being misgoverned,” opposition leader Henrique Capriles Radonski demanded this week.

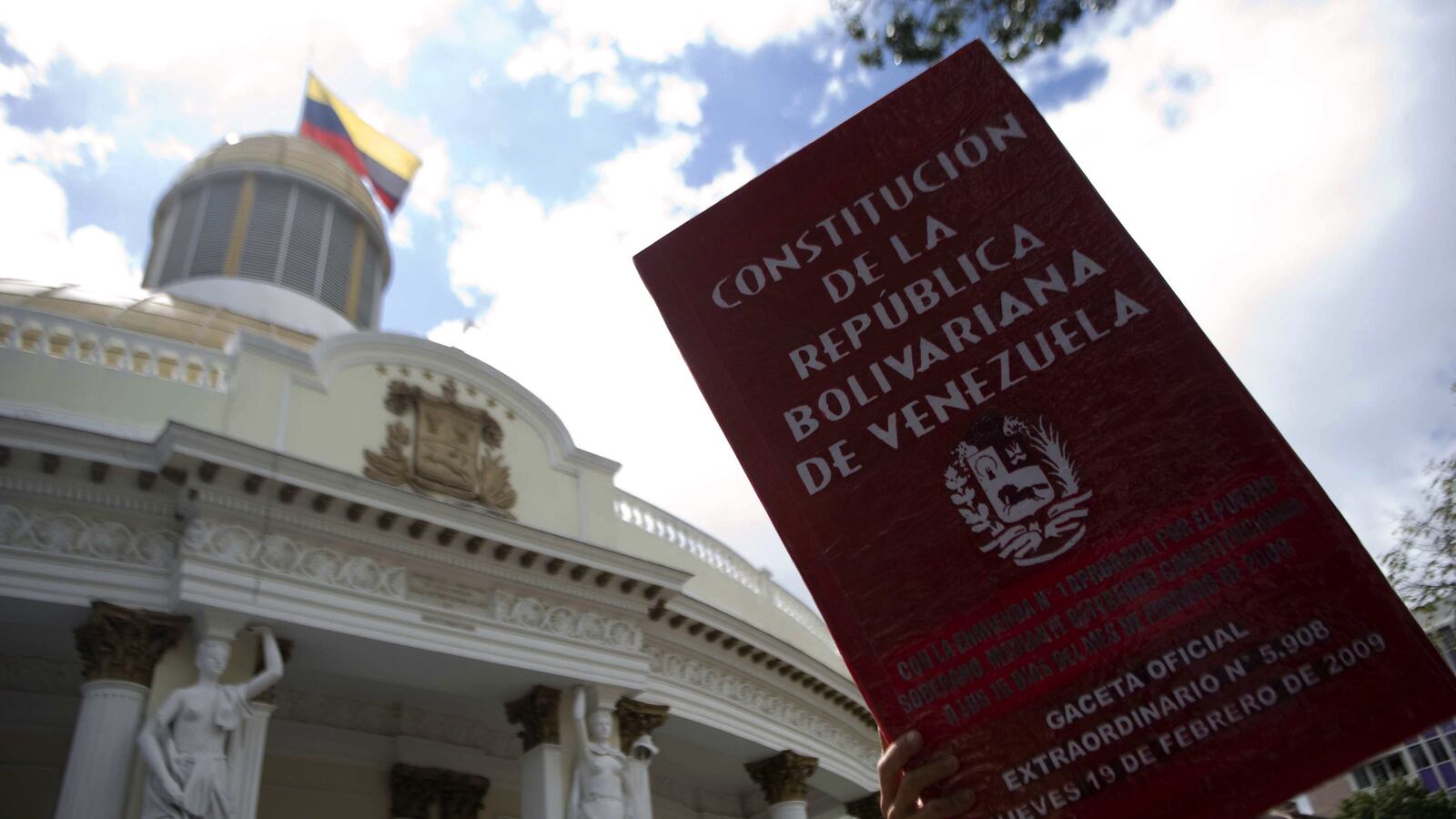

And yet neither procedure appears to be moving forward in the so-called Bolivarian Republic, where critics charge that a self-designated junta of Chavista insiders is making up the rules as they go. The Venezuelan Constitution—written to order by Chávez’s allies—has already taken a hit. According to article 234 of the charter, if an elected leader is, say, ill and temporarily unable to take the oath of office, the head of the National Assembly takes over, triggering a legal countdown. The president-elect has a total of 180 days to recover and be sworn in.

If, however, the unsworn president dies or is permanently incapacitated, constitutional article 233 kicks in, ordering the National Assembly to call a new election. Within 30 days, Venezuelans return to the polls and the caretaker government takes its bows.

That is not what has happened. When Chávez failed to show at his scheduled Jan. 10 inauguration, it was former vice president Nicolas Maduro who took the reins instead of the head of the National Assembly, Diosdado Cabello.

This is important, because while both are card-carrying Chavistas, they represent competing strains of the fractious ruling claque. Former vice president Maduro, a onetime bus driver and foreign minister who favors red shirts and a mustache, is said to be close to Cuban President Raúl Castro, Chávez’s political mentor and fastest ally. Cabello, for his part, is an old military buddy of Chávez’s who helped the Bolivarian “comandante” plot his failed coup in 1992, and is said to enjoy sway over the Venezuelan armed forces.

Strengthening Maduro’s claim is the fact that Chávez named him as his favored successor just prior to flying off to Cuba. The opposition quickly cried foul. In Venezuela, they noted, the vice president is not elected but appointed by the sitting president. And since Chávez was never sworn in to his new mandate, Maduro’s term also ended on Jan. 10. He currently holds sway not as Chávez’s lawful successor but as his personally anointed heir.

Giving the maneuver the varnish of legality was the Venezuelan Supreme Court, which is packed with Chavista appointees, and in a pearl of constitutional jurisprudence declared the inauguration a mere “formality,” given that Chávez was reelected. No change of guard, no oath required. So in lieu of Chávez, the ruling junta ad-libbed, declaring that it is the “Venezuelan people” who have taken the oath of office.

Whether such tortured rulemaking matters to Venezuelans is another matter. “The current situation is a clear deviation from the Constitution,” says Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington-based policy and research group. “But this is not a country of constitutionalists. The common sense out there is that this guy was reelected, and there’s an enormous amount of sympathy and compassion for him on the street.”

Just ask Willie Colón. In an irreverent tweet on Friday, the salsa idol and New Yorker, who has a wide following in Venezuela, tossed out an off-color pun: “God bless Venezuela, with two presidents … one is Maduro [Spanish for ripe], and the other, rotting.” The backlash was instant and massive, a show of force of the Chavista cyber-shock troops. “Do not dare come to our country,” Venezuelan Minister of Prison Affairs Iris Varela shot back. “Twenty million Venezuelans will repudiate you!”

"Thank you for making me a trending topic in Venezuela!” the undaunted Colón parried the next day, inviting visitors to his Facebook page.

What’s also impressive is how much support Venezuela still musters from its Latin American neighbors, some of whom Chávez has blessed with generous shipments of discounted Venezuelan crude oil (Cuba, Nicaragua) and others (Argentina) by buying up government bonds that no one in the markets will touch. It’s no different in Brazil, Latin America’s rising democratic powerhouse, which enjoys a $4 billion trade surplus with Venezuela—and routinely declines comment on charges of human-rights violations or breaches of democracy in Venezuela.

The few who do speak out often feel the Bolivarian backlash. So it was last week when Guillermo Cochez, Panama’s ambassador to the Organization of American States, chided the region’s diplomats for turning a blind eye to the constitutional irregularities and violations of Venezuela’s “ailing democracy.”

“Latin America today is divided between ideological allies" who share Chávez’s “jaundiced view of democracy," and those “who look the other way because of economic interests,” Cochez told The Daily Beast. “If we cannot agree on democratic principles, we might as well close down the OAS.”

The comments stirred the wrath of Chavistas across the region, and played badly in Panama City, which receives cut-rate oil under Venezuela’s Petrocaribe program. The next day, Cochez was fired.