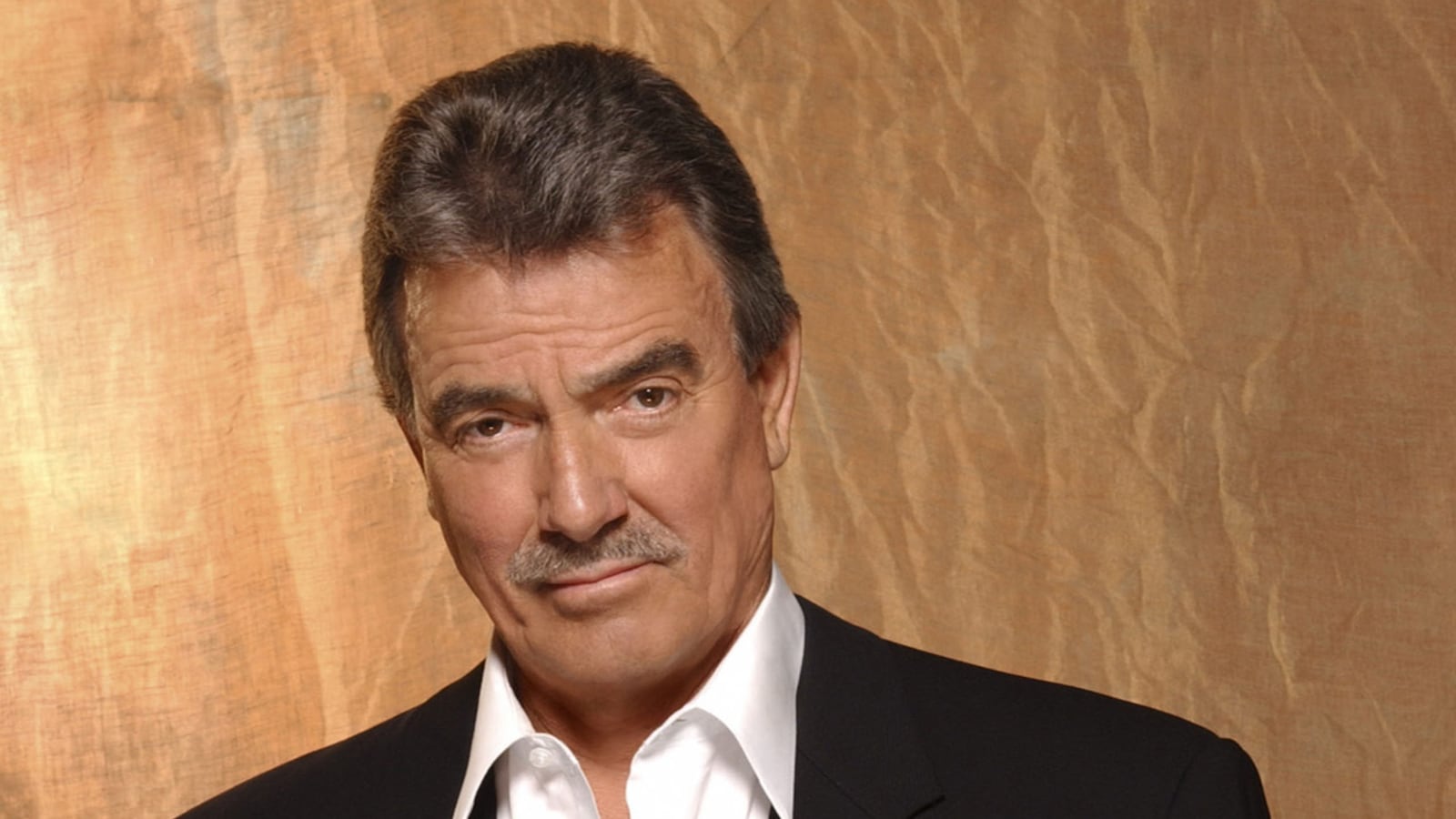

It’s very Victor Newman, my first sighting of Eric Braeden in the plush lobby of New York’s Plaza Athénée hotel. Dressed all in black, the handsome 76-year-old actor observes me hawkishly, and without a word raises an index finger indicating that I should follow him into the dark confines of the hotel’s café.

He may as well be his character—the all-seeing kingpin and menacing and protective paterfamilias of long-running soap The Young and The Restless. And we may as well be in the Genoa City Athletic Club, the Newman ranch, or Victor’s office at Newman Enterprises, whose wall is memorably adorned with “the Moustache’s” wily-expressioned portrait.

Victor has survived every soap opera calumny: corporate chicanery, murder attempts, poisoning, and amnesia. He has done his share of terrible things too, most notably substituting his nemesis Jack Abbott (Peter Bergman) with an impostor who—in one of the show’s most repellent recent stories—raped Jack’s unwitting wife Phyllis (Gina Tognoni) over and over again for a period of months.

Now, a new writing team has made Victor kindly and sweet, dispensing wisdom and warmth to his family—but surely the iron-fisted schemer within hasn’t expired completely.

As any Y&R fan knows, Victor’s anger, when it flashes into abrupt, Germanic-twanged life, is pretty terrifying—and just as Victor shows over and over again that he is not to be crossed, so a couple of hours with Braeden suggests that his portrayer isn’t either. He is both softly spoken, and quickly, emphatically furious.

Braeden’s anger is especially evident when it comes to insisting that he will “go after” anyone who crosses or undermine him, and also with the mention of Donald Trump, who you might expect Victor Newman to have much in common with, but not so Braeden who angrily denounces the president as a “clown,” whose policies are “bullshit” (a favorite word).

The ethos of Trump’s presidency echoes fascism, Braeden says, and this is something he feels passionately about. His much-loved father, who died when Braeden was 12, joined the Nazi party, and in his just-published memoir Braeden writes movingly about the anger and confusion that this has caused him in the years since.

One of Victor’s most famous catchphrases—“I’ll Be Damned”—is also Braeden’s, and so it makes the perfect title for the book.

Where the line ends between a well-known character and their portrayer is always fascinatingly drawn, particularly with a soap opera actor. Braeden, born and raised in Germany, has played Victor since 1980, the character and actor both genre leaders and legends.

The CBS drama, 11,112 episodes old and celebrating its 44th birthday on March 16, leads the pack of the four surviving daytime soaps. They are an embattled and much-mocked genre, and Braeden a staunch defender of them.

***

The death of his father was “the most emotionally difficult moment” of Braeden’s life. “The juxtaposition of what happened historically during that time and what I know of my father was difficult to reconcile,” he says. “Yet having studied the period I understand full well why he believed in Nazism.”

As Braeden notes, Hitler’s ascendancy was powered by his dragging Germany out of a Depression. “In 1928 people thought he was a nut, no-one took him seriously. German Jews didn’t take him seriously.

“The Weimar Republic, one of the most liberal constitutions in the world, failed because of the Wall Street Crash, providing a fertile ground for real disgruntlement and fear in Germany. Then along comes this raving maniac promising to defy the Versailles Treaty and re-establish German pride. The German people said ‘yeah.’ Now, we have this idiot here (Donald Trump) who says he wants to make America great again.”

Braeden’s father began to have doubts about the Nazis in 1941, according to a family friend. He wasn’t aware of Jewish mass murder but like many Germans he did not want another war: “After the First World War, Germans were exhausted,” Braeden says.

After World War Two, his father was “de-Nazified” by Allied troops. Father and son never spoke about what had happened during the war. Braeden later, then living in America, wrote anguished letters to his mother asking for answers.

She would only tell him that her husband had built roads, provided trucks, and later oil storage facilities for the Nazi regime. “It was a question of survival,” Braeden says. “Brecht said, ‘First comes a full stomach, then comes ethics.’ That’s a fact. I understand what my father did, of course, absolutely. These were economically dire straits in Germany. How was he going to get out of that?”

At 18, fresh to America, and studying at the University of Montana, Braeden recalls being asked how a country that produced Beethoven, Wagner, Brahms, and Brecht could produce Hitler. “How am I going to fucking answer that at 18?”

To make it in Hollywood, he changed his name from his birth name, Hans-Jörg Gudegast, to Eric Braeden. At one Hollywood party Braeden was told if he wasn’t a German actor he’d be a huge star. He had lunch with Albert “Cubby” Broccoli, who was interested in him playing James Bond. The discussion abruptly ended when he discovered Braeden had a German passport.

Playing Nazis became staple employment. “I felt dehumanized by perpetuating that image,” says Braeden. “I think that Hollywood contributed enormously, as did I, to the dehumanization of everything German. ‘German’ was synonymous with ‘Nazi.’”

His voice rises. “Germans are the largest ethnic group in America, did you know that? Do you know the contributions of German immigrants into his this ountry? Substantial. Fundamental. And yet we are measured by that 12-year fucking period run by an Austrian fucking private. It’s so enraging sometimes.” (He once served on the German American Advisory Board alongside General Alexander Haig, Steffi Graf, and Henry Kissinger.)

Has writing this book helped Braeden exorcise all these demons? “I must say no, not really,” he says, gravely.

The changes of Victor, his storms and different shades, make him an “enduringly interesting” role to play. “I’m immensely grateful having done it all these years,” says Braeden. A seminal moment came when it was revealed he had been abandoned as a child, and this after he went to the show’s co-creator William J. Bell to say the character needed more depth than just being villainous.

“I had played the villain for too many years in night-time television and film. Look at my IMDB. I’ve probably played more bad guys than almost any other actor. I was determined for a long time to get out of the rut of playing Nazi number one and Nazi number two.”

A Broadway show in 1965 and the TV series The Rat Patrol, he hoped, would change that. But two shows into The Rat Patrol, his German Nazi character, whom he thought was going to be complex, suddenly acquired a limp and an eyepatch. “I said, ‘Go fuck yourselves. I won’t do it. I’ll play him as a human being and that’s it.’ To constantly depict the Nazi as a convinced ideologue is uninteresting. I want conflict, ambivalence. The Steve Bannons to me aren’t interesting. Are you kidding me?”

Braeden is referring to Donald Trump’s Chief Strategist, says he doesn’t want to enter into “a long political diatribe” and instead will “hold back”—and then does neither.

“The essence of fascism is simplifying complex problems, or rather explaining them in simplistic ways,” says Braeden of Trump and his lieutenants. “To now tell a lot of disenfranchised, unemployed blue-collar workers in the Midwest that it is all due to Obama is bullshit. It is due to globalization and automation. Will the genie ever go back into the bottle? It can’t. And this bullshit artist is certainly not going to fix it. He can’t. The only way you’re going to re-employ disenfranchised, unemployed blue-collar workers, whose pain I understand, is to start the kind of public works program that Obama wanted to start.

“The Republican Congress, led by Mitch Fucking McConnell stopped every attempt at spending public monies on rebuilding America’s falling-apart infrastructure. That would have employed millions of people for quite some time.

“Trump won’t bring these jobs back unless he rebuilds America infrastructure with public funds, but he’ll make sure a lot of private people make a lot of money in the process. It’s utterly dishonest and disingenuous, and pulling the wool over the eyes of a lot of disenfranchised people who I feel very sorry for.”

Part of Braeden’s ire is reserved for Democrats who did not “explain sufficiently” how they could help blue-collar and disenfranchised workers. “In all honesty neither Democrats and Republicans have a succinct answer for it. It’s all bullshit. What Obama and Hillary should have done is to say that Obama saved GM’s ass by spending public monies and saving hundreds and thousands of jobs.”

It makes Braeden furious that politics is so partisan and ideological rather than looking at problems practically. “This clown says he is going to make America great again. America is great. I’m an immigrant. I know. It has its faults, but who doesn’t? America is great. Are you kidding me? It’s always trying to renew itself. Look at what comes out of California. I love it. It’s one of the most productive states in the world.

“This country is being fucked up by partisan politics. George Washington warned of hyper-partisanship to the point where it becomes so recalcitrant and impenetrable and inflexible that no compromise is possible. I don’t give a damn whether someone agrees with what I said or not—that’s the truth.”

The Obamas, says Braeden, “are two of the most scandal-free, decent, intelligent people ever to occupy the White House, and they were vilified by fucking Mitch McConnell. Do you know how that fills me with anger?”

Hillary Clinton had her faults, Braeden accepts, but she impressed him and so did her husband, “apart from deregulation the financial system regulations which led to the calamity that Obama bailed us out of afterwards.

“Now these idiots are undoing that, and it isn’t for the common man. It’s for the fat cats of Wall Street. Period. It’s an obvious abuse of power to pull the wool over those blue-collar workers and those out of a job who are really suffering.

“This clown is not going to do anything. It’s a farce. Where I get my continued anger from is that people don’t realize that the essence of fascism is offering a simplistic solution to complex problems.”

Braeden is disturbed “terribly. What is this Muslim Ban? It’s a bunch of bullshit. They didn’t apply it to Saudi Arabians. There’s no ban against them because we have deals with them. Give me a fucking break, it’s hypocrisy.”

Watching the news is just as enraging. “At least CNN tries to be fair and get both sides. The other one (Fox News) calls itself ‘fair and balanced,’ but how can you watch it? It’s fucking bullshit.” Via apps on his phone, he reads The New York Times, Der Spiegel, BBC News, and the New York Review of Books every day.

Does Trump share anything in common with Victor Newman? Braeden laughs. “The kind of power Victor Newman has is similar. Yes, he abuses his power too. And I can imagine Donald Trump firing up the Trump jet, just like Victor would, to take his date to Paris.”

***

Braeden and his wife, Dale, married in 1966. They have one child—a son named Christian, whom Braeden speaks extremely affectionately about—and three grand-daughters whom he’s devoted to.

He and Dale wanted more children, and both regret it, but Christian’s birth was difficult, and later Dale suffered a near-fatal bout of appendicitis, requiring a major operation on her abdomen.

“She would have loved to have had a girl,” says Braeden. “She’s a feminine woman who lives with this man whose interests are mainly sports and politics.”

Theirs is an enduring marriage. “Once someone suggested some couples’ therapy. I went reluctantly, and met the shrink who was as cold as a fish. I said, ‘Listen, do you honestly think I am going to tell you about my inner feelings?’ I said to my wife, ‘Darling let’s get the hell out of here.’ That was my only encounter with a shrink. Show me a relationship that doesn’t have trouble at one time or another, and I’ll show you two idiots.”

How swinging were his 1960s? “When you work out as hard as I did, the swinging is limited. You can’t compete in sports and be out too much. It’s bad. The terrible thing is I smoked for 20 years. I started because I wanted to impress an older lady on the ship on the way over here. It’s the most addicting thing there is. I got terrible bronchitis, and gave up at 42. Now I can’t stand the notion of it.”

The nature of his high-profile profession meant “things get tough” in a marriage as long as his. Has Braeden been faithful? “Yes of course. I deeply love the fact she has supported me all those years psychologically and encouraged me. She has an artistic soul. I come from a more bourgeois upbringing, with not a lot of artistic sentiments. I grew up in the countryside, worked and survived, yet had a longing for the other. She in a sense is the other, to put it very simply.”

Dale was a Europhile who introduced Braeden to the work of Balzac, Seurat, Cézanne, Picasso, and Monet; and to Ingmar Bergman and Woody Allen films. Her artistic sensibility, Braeden says, is yoked to a sense of practicality and pragmatism. She grew up in Hollywood. She knew its phoniness.

Has he been a good husband? “In some ways yes, in some ways no.” In which ways no? “I cannot tell you that. I have always been very protective and supportive of my family. When I had nothing she always encouraged and supported me. I will never forget that. You never turn your back on people who helped you or your early friends—and she obviously far more than that.”

Braeden writes in the book about Dale and another young love, but that’s it. Did he have lots of other sex and romances? “That’s a subject matter…” he sighs… “I won’t talk about. I really don’t. I mean, I’ve worked with some very beautiful women: Raquel Welch, Jennifer O’Neill, Lynda Carter…” Silence. “This is something we won’t talk about. You end up hurting people, and I don’t want that.”

Has he improved his behavior when he’s behaved badly? A long pause. “I hope so.”

Victor is terrible at admitting fault. Is Braeden better than his character? “I’ll argue with you, but yes. I’ll fight you, but upon reflection say, ‘She’s right.’”

One might get the feeling these moments don’t happen so often, but he tells a story about coaching Christian in soccer. Christian reprimanded his father for saying, “You did well, but…” at the end of a game. Christian told his father that “but” had hung over him “like a sword of Damocles.”

Braeden asked how he should have offered criticism, that he would feel remiss in not “offering extra knowledge and wisdom.” Christian told him to voice it at the next practice, like the other dads.

Braeden accepts that in some ways he has been too critical of his son, but “if you’re a good-looking guy of a certain size people will fuck with you and challenge you.” He took Christian to New York’s Central Park at 14 to teach him to be aware of his surroundings. “You learn that when you lose your father early on.”

Two female prostitutes recognized Braeden as Victor Newman and asked if there was anything they could do for him. “I said ‘thank you very much,’ and that I was with my son. ‘We’ll teach him,’ they said.” To which Braeden replied: “No that’s fine.”

Noting my British accent, Braeden talks about soccer—a longtime passion, he played for years—and proudly shows me the apps for the U.K. Premier League and German Budesliga. His friends today are athletes and sportsmen, he says, “people of accomplishment.”

“I’ve basically always had disdain for Hollywood,” he adds. “I don’t give a shit about Hollywood. I don’t care. I respect the work enormously, but going to a party and blowing smoke up someone’s ass? Who gives a fuck? I couldn’t care less. You can live on the moon and they will come and get you if they want you.”

Instead, for Braeden, there are his lifelong friends from the Maccabi Jewish soccer team in Los Angeles, whom he played alongside for many happy years, and his closest friend Michael Meyer, the Adolph S. Ochs Professor of Jewish History Emeritus at Hebrew Union College.

Braeden himself participated in track and field as a teenager—the discus, shot put, and javelin—and later boxed. He still works out every day: his shirt barely contains his bulging arms. “Keeping in shape is the best medicine there is,” said Braeden. “Everything else is bullshit: therapy, drugs, forget it. Keep in shape.”

And keep working. He likes the complexity of Victor—all his crazy journeys from dark to light, his ruthlessness offset by moments of vulnerability, the pain and the lack of trust he has even for those closest to him. “That’s the genius of the storyline. That’s why I’m staying.”

Victor and his wife, Nikki, are a highly prized soap “supercouple.” But watching their relationship in past years, it also seemed (to this viewer) abusive, with Nikki subservient to Victor, and the regular focus or victim of his furies.

“It’s an interesting question,” says Braeden. “I understand, but there’s another aspect to this. I’ve known a lot of couples in real life where women are the biggest bitches around and demean their husbands left and right. That’s not women’s liberation. True liberation should be that they talk to each other and where there’s mutual respect.”

He says he grew up surrounded by strong women, and believes in true equality.

“If you talk to me in even a slightly condescending way I’ll come after you, man or woman. Don’t make me the schmuck. In all American commercials the man is seen as the schmuck. That’s bullshit.”

Should Victor always be with Nikki? “At the end of a very long day, yes. I love working with her (Melody Thomas Scott) and we have a very good understanding.” But they’re not close friends. “Every actor will tell you that’s a dangerous road to go down. It’s like workplace romances: you have to be very careful about that stuff.”

His and Nikki’s house, the grand Newman ranch, doesn’t seem that grand. “That house,” Braeden says with a sigh of horror. “I come on to the set every day and say, ‘This is a retirement home in some abject suburb of LA.’ Are you kidding me? Who came up with this nonsense? It will be changed eventually.”

As for Victor tacitly overseeing Phyllis’ continued rape for months, Braeden says, “Victor Newman has nothing but disdain for Jack Abbott. So he didn’t give it a shit about it. He enjoyed it. As Eric Braeden I wouldn’t entertain this in the remotest way.”

Without mentioning his name in the memoir, Braeden rips into Michael Muhney, who played his son Adam on the show. The two feuded royally, Braeden writes, with Braeden feeling like Muhney wanted to imperil his position on the show. Yet now Justin Hartley—Muhney’s replacement—has left the big-fame shores of NBC hit This Is Us, some fans want Muhney to return to the show. “I’ve never mentioned his name. I never will mention his name,” says Braeden. “He was a very good actor.”

Braeden hated the Y&R storyline which saw Victor marry his daughter-in-law. His vision, he tells me, was that Victor should sleep with Sharon, wake up the next morning, regret it, then run off to hide in a Greek monastery. Staying one step ahead of those searching for him all around the world, Victor would end up living as a drunk among the homeless of LA.

Would Braeden ever leave the show? “No. No. Look at the basic reality. Let’s not bullshit. There are 150,000 registered actors in Hollywood. That means there are 400-500,0000 more of whom who can’t make a living.

“I’m one of the luckiest bastards to have worked since 1962. I kiss the ground I walk on. I may get pissed off about this and that, but I am blessed in that sense. I’m very conscientious about doing the work and helping the show. I know what it means. I’ve worked with big stars in the past. Where are they now? Either dead or unemployed.”

Soap opera is an embattled genre: only four survive now compared to the 13 that Braeden recalls in their heyday.

“I’ve always felt soaps should be as close to reality as they come. They need to be as honest as they can be. Because of Showtime, Netflix and all the others, audiences are now used to very tough and real stories. Daytime needs to adopt or adapt to those styles. Audiences are intelligent, and it’s arrogant for people in New York or Hollywood to think they are not.”

Will Y&R survive? “Yes, as long as the major characters survive.”

Of Mal Young, the show’s British executive producer, Braeden says, “At first I thought, ‘Who’s this Brit coming here?’ But the moment I talked to him I liked him. He was a human being I could relate to immediately. No bullshit. He loves actors. He gets all the things that need to be changed. It’s a visual medium. What’s all this bullshit of sitting there and talking to yourself? Imagine it, or say it in voiceover.”

But still there is a snobbery to soap operas and the actors who work on them. “Those condescending assholes who would piss in their pants if they had to do the amount of work we have to do,” says Braeden. “Are you kidding me? I’ve done it all, from Broadway to movies. This is the hardest job in the business.”

The snobbery is “perpetuated by the media and the term ‘soap opera.’ It is perpetuated by the award shows for daytime which have the worst producers imaginable who try to satirize what doesn’t need any more satirizing—instead of showing great scenes and great actors.

“Don’t denigrate a medium where we shoot over 100 pages a day. Film shoots two pages a day, and nighttime eight to 12. Daytime performances are fantastic given how little time we have—usually just one take. Are you kidding? It’s extraordinary: it should be a much more elevated medium. I told Bill Bell that he should stop going to the Daytime Emmys. Fuck it, don’t. It’s a laughing stock. So I won’t go. It’s a joke. It’s ridiculous. I find it insulting.”

How does he feel about his nickname of “the Moustache”? He grew one originally for Gunsmoke, he says, and he’s fine with being called it on Y&R, although he was told he could no longer call Jack, “Jackass Abbott.”

***

Anger, he writes in the book (and as displayed today), seems to be one of Braeden’s chief animating forces.

“I like it. I have nothing against it,” he says. “It’s the driving force in my performances. It has made me a lot of money as an actor. But obviously I can’t do that as a private person.”

Where does his anger come from? “When you lose your father between 10 and 14/15, a father you idolized, there are no answers,” Braeden says. “You begin to ask the most fundamental questions. I grew up a Christian Protestant and it gave me no satisfactory answers at all. None. It’s all a bunch of blarney. But you’re angry because you are left by father you adored. Then you are plunged into poverty. My mother is a proud woman, and I saw her go through the indignities of poverty.”

The anger, he says, “is me. It’s in me. It’s visceral. I grew up in a tough world. You settled your shit with fists.” Has he learned to control his anger? “Of course, you have to for self-preservation. I meditate a lot and I work out a lot.”

I ask how Braeden feels about aging. “I love it, fuck it,” he says cheerfully, dreamily quoting “rage, rage against the dying of the light” from Dylan Thomas’s poem “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night.”

He has had no plastic surgery or work done. “I am who I am. Why would I pretend to be 55? I am 76 and proud of it. Working out is the best medicine, and don’t forget to do weights. It’s good for your joints. And walk, walk.”

When I ask about his mortality, Braeden quotes the “perchance to dream” passage from Hamlet. He loves Shakespeare, and performing Shakespeare. “He is it. He’s the shit. He is one of the greatest geniuses who ever lived. Ever.” And then he dreamily quotes the “Life is but a walking shadow,” speech from Macbeth.

When I ask about Braeden’s future ambitions, he instead talks proudly about his son Christian’s writing and directing career.

“There’s almost no richer role than Victor Newman,” he insists. Fame. Braeden says, is very nice. “Anyone who says it isn’t is full of shit. Ninety-nine percent of people approach you in a warm, kind way wherever you are in the world: Tel Aviv, Istanbul, Harlem, LA, New York City. But don’t take it personally, or you’re fucked.”

He recalls seeing the footballer Pele at a glamorous L.A. restaurant once—Sean Connery, Gregory Peck were there that night—and Pele went immediately to greet the kitchen staff. Muhammad Ali had a similar, welcoming grace, he says. “I’ve always been very measured about fame. I know how short-lived it can be. It’s a fool’s dream to take that seriously, so I take it nicely, gratefully, thank you.”

Y&R fans are particularly dedicated. That was overwhelming initially, says Braeden, but now he is appreciative of their devotion. He has learned to be grateful.

Don’t think, he says, that these fans are all middle American housewives either. Braeden once met former Israeli president and prime minister Shimon Peres, whose wife watched the show (“I’m not sure he did"), and he also cites George Foreman, Muhammad Ali, Tommy Hearns, Sugar Ray Leonard, and team members in the New York Yankees, Oakland Raiders, and LA Lakers as fans.

On the streets of Paris—where Y&R is shown as the impossibly French and wonderful-sounding Les feux de l'amour—people greet him with, “Hello Victor, Ça va?” In Istanbul, at the main bazaar, Braeden emerged from looking at carpets to hearing a crowd chant Victor’s name.

When I ask about the notion of retirement, Braeden says forcefully, “I loathe, loathe loathe it. What for? I’ve seen friends who have and become old men in no time at all.”

He doesn’t really hang out with his co-stars, he says. Some he is closer to than others. “I encourage the younger ones, but if you come after me you better watch it. I don’t care who you are. I’m not into being an asshole to someone at the beginning. I’m very welcoming. I just want a good scene. But if I see it or sense it, I say to them, ‘You’re fucking with the wrong guy.’ Because we live in such a litigious society, they’re still walking around in one piece.”

There’s an old story about Braeden and Peter Bergman (Jack Abbott) having a physical fight in the early 1990s. “I can’t talk about it,” Braeden says. “But I’m very sad about our disagreement at that time.” Are they buddies? “I would not say that,” Braeden says equably, “but I respect him and that’s all we need to do at work. We don’t need to become buddies. I have my friends and he has his friends.”

I ask if Y&R should become more topical and controversial, as many of the British soaps that Mal Young has overseen have been. “No,” says Braeden, “people want to be entertained, and deal with the fun and emotions of families.”

There are currently no out LGBT characters on the show, and the show has flailed writing them before. Braeden has nothing to say about that, and confesses, “I don’t watch the show a lot. Sometimes I’ll watch my performance back. Not often. I get pissed off about too many things. That’s one tragedy, because as an actor I have limited power and I don’t want to be a pain in the ass. But I see so many things, and want to say, ‘Why did you let that go through?’ ‘That should have been done another way.’ It’s an exercise in frustration.”

He does not challenge the writers on what they write for Victor. “I have enormous discipline and do, generally speaking what is written.”

Is Braeden a perfectionist?

“In some ways I am, but I accept my limitations, you know.”

***

Braeden has had sorties away from Y&R: he had a part in Titanic, and calls director James Cameron “a fucking genius with brass balls” for standing up to nervous studio bosses, fearing a flop, to realize his epic dream of a movie.

But Braeden’s stardom has stayed in daytime and not transitioned to a bigger, different kind of celebrity in primetime or on the big screen. Would he have liked that? “I’d be a hypocrite to say ‘no.’ But most of the primetime actors of the 60s and 70s are gone. Where are they now?”

What is the magic of Victor and Y&R, does he think?

“The essence of Victor and the essence of Eric Braeden is to not take any shit. It’s also about power. ‘Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely,’” Braeden says, quoting Lord Acton. “I think people like to see storytelling too. Storytelling is as old as the Iliad, and before the Iliad they was verbal storytelling.” Soaps like The Young and The Restless are morality plays, he says.

Victor Newman will soon return to his office to plot and scheme. Braeden had wanted the producers to humanize the rape-facilitating, ranting gargoyle Victor had become, which is why he’s been stuck at that ranch that looks like a retirement home providing warm counsel to all and sundry.

“He’s been gentler for a while,” Braeden says. Then he smiles, and grins as wickedly as only Victor can. “But the shit will hit the fan again.”

I’ll Be Damned: How My Young and The Restless Life Led Me To America’s #1 Daytime Drama by Eric Braeden (with Lindsay Harrison), is published by HarperCollins/Dey Street Books.