I once recommended Colm Tóibín’s The Master to one of my students. It has nothing to do with P. T. Anderson’s movie—Tóibín’s book is all about the masterful novelist Henry James. But not everyone knows Henry James’s work. My student didn’t. Nonetheless when several weeks later I debriefed him, it was clear that it almost didn’t matter. Tóibín’s deft act of characterization had come through.

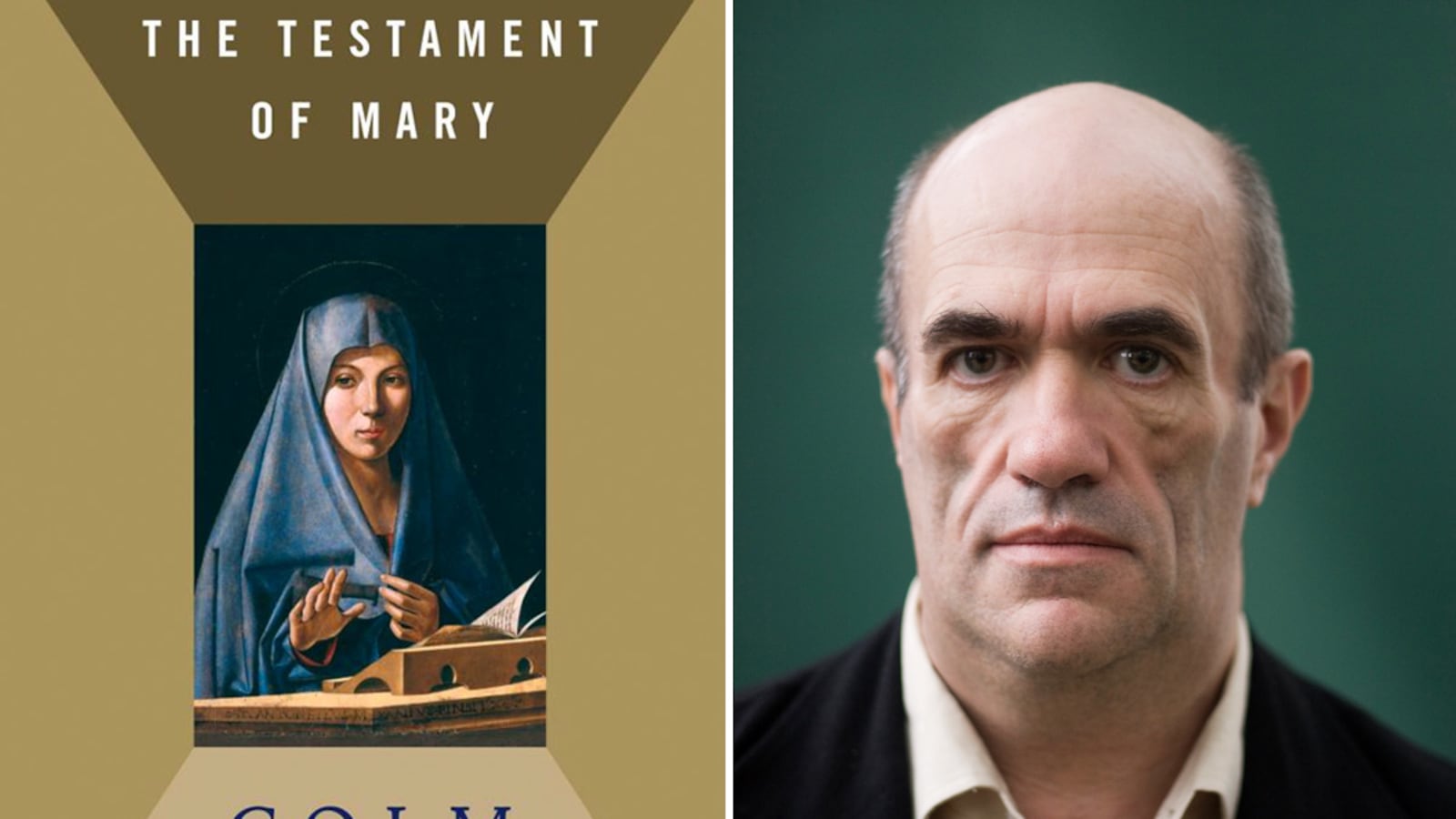

I’m not sure I’d recommend Tóibín’s new book, The Testament of Mary, to anyone who hasn’t at least looked at a Christmas crèche and spared a thought for the Virgin’s dignity and her poise. You don’t have to be a Roman Catholic to respond, at a deep level, to Tóibín’s new book. But a novel about the Virgin Mary can’t help but be a provocation—a gift, if you will—to those of us who care.

The best parts of such a book are supposed to be blasphemous. How far in can Tóibín reach, into the holy of holies? How deep an impression can his imagination make, on mine? In The Testament of Mary he scores probably two images I won’t soon shake.

The Gospel of John tells of Lazarus, a young man, four days in the grave, whom Jesus brings back to life. In Tóibín’s account, the resurrected Lazarus can hardly talk. He eats only small pieces of bread, moistened by his sisters. In Mary’s opinion, Lazarus will soon fail once more: “If [Lazarus] had come back to life, it was merely to say a last farewell to it.” The miracle may have been real—but was it merciful?

And Tóibín turns Jesus’ disciples into teenagers. Mary recalls the “group of misfists” who used to come over to the house: they were “only children like himself, or men without fathers, or men who could not look a woman in the eye. Men who were seen smiling to themselves, or who had grown old when they were still young.” In his excellent essay on Christian youth, “Upon This Rock,” John Jeremiah Sullivan recalls the years he spent in an evangelical cell-group of “grad-seminar intensity” that was “accepting of every kind of weirdness.” It rhymes perfectly with Tóibín’s image: it’s easy to imagine Mary rolling her eyes.

Her very lifelike skepticism is what makes The Testament of Mary more than a provocation. Mary seems fallible: she’s an unreliable narrator. And like the gospel writers themselves, Tóibín has shuffled events in order to draw his lesson. In John, at the wedding at Cana, where Jesus turns the water into wine, is the beginning of his miracles. And it notably signals his independence from his mother: “Woman, what have I to do with thee?” Jesus asks, when Mary speaks to him. Tóibín delays the wedding, so that it comes just after the Lazarus episode, and hence at the beginning of the end—for the Pharisees, hearing about Lazarus, have finally decided to do something about this upstart from Galilee. In Tóibín’s telling, then, Mary is perfectly positioned to warn Jesus of the dangers he faces. And his rejection of her makes more dramatic sense.

For Mary’s skepticism toward Jesus’ mission is premised on an overprotective love for him. Other writers have imagined a doubting Mary. Pär Lagerkvist, who won the 1951 Nobel Prize for his Barrabas, has the eponymous thief watching the crucifixion, noticing the interested bystanders, concluding that one of them is Jesus’ mother: “She probably felt more sorry for him than they did, but even so she seemed to reproach him for hanging there, for letting himself be crucified.” It could be a universal intuition: that Mary wouldn’t thrill to the bloody apocalypse.

In an early bid to make his Mary more likeable, Tóibín has her remember the Sabbaths of Jesus’ youth: the stillness, the spreading sense of goodness and comfort. “The best time was when my son was eight or nine, old enough to relish doing what was right without being told, old enough to remain quiet when the house was quiet.” She doesn’t just like peace, she insists on it. She remembers with teeth on edge the days when Jesus first began to preach, “his voice all false, and his tone all stilted.” After his friends went home, she says, Jesus always grew less agitated, like a vessel “filled again with clear spring water which came from solitude, or sleep, or even silence and work.”

Tóibín was raised an Irish Catholic in the town of Enniscorthy. In his essay “A Native Son,” collected in The Sign of the Cross, his teenage faith gradually fades; he decides that in his community religion is “consolation, like listening to music after a long day’s work.” Later in the same volume he writes movingly of ambiguous adult moments, during a visit to Lourdes and again during an experiment with ketamine, when something like faith, or at least sentimentality around the idea of faith, definitely flickers.

He is no James Joyce then, who would deny his mother a Christian confession on her deathbed. In Mary, he sees a sinner like himself—a friend of Christians, but a black sheep. He leaves open the possibility that the Resurrection actually happened: Mary flees the authorities in Jerusalem, and is on the road three days later when she has a very powerful morning dream. But the dream fades. This is her temperament: she wants dreams to belong to the night. “And I wanted what happened, what I saw, what I did, to belong to the day.”

I insist on using the word “blasphemous” to describe this mild, thoughtful novel, because I think much of Tóibín’s point is that a good novel can’t help but blaspheme. It may no longer make emotional sense for us, as it did for Joyce, to begin a great novel with Buck Mulligan horsing around with his shaving kit, pretending to be a priest. But there’s an ars poetica in Mary’s stubbornness and refusal to tell her story neatly. She complains that the gospel writers who interview her always “try to make connections, weave a pattern, a meaning into things”; she mocks their “earnest need for foolish anecdotes or sharp, simple patterns.” Mary is always remembering odd details, useless to these men who are trying to change the world. Her testimony—with its careful construction of personality, its subjectivity—can’t help but undercut the storytelling style of the New Testament.

That style probably deserves more credit than Tóibín's Mary gives it. Her dream, of Christ's resurrection, is, she says, easy to imagine. "It is what really happened that is unimaginable." Tóibín speaks up for the reality of the horror of the crucifixion. But it’s a reality we wouldn't care about, had Mary's examiners not written the New Testament. No man gets to its "what happened" except through it.