Who does John Roberts think he is?

Who knows? Not after June 28, 2012, anyway. Not after Roberts delivered the majority opinion in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, which upheld President Barack Obama’s Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act by a five-to-four margin. The healthcare ruling changed everything.

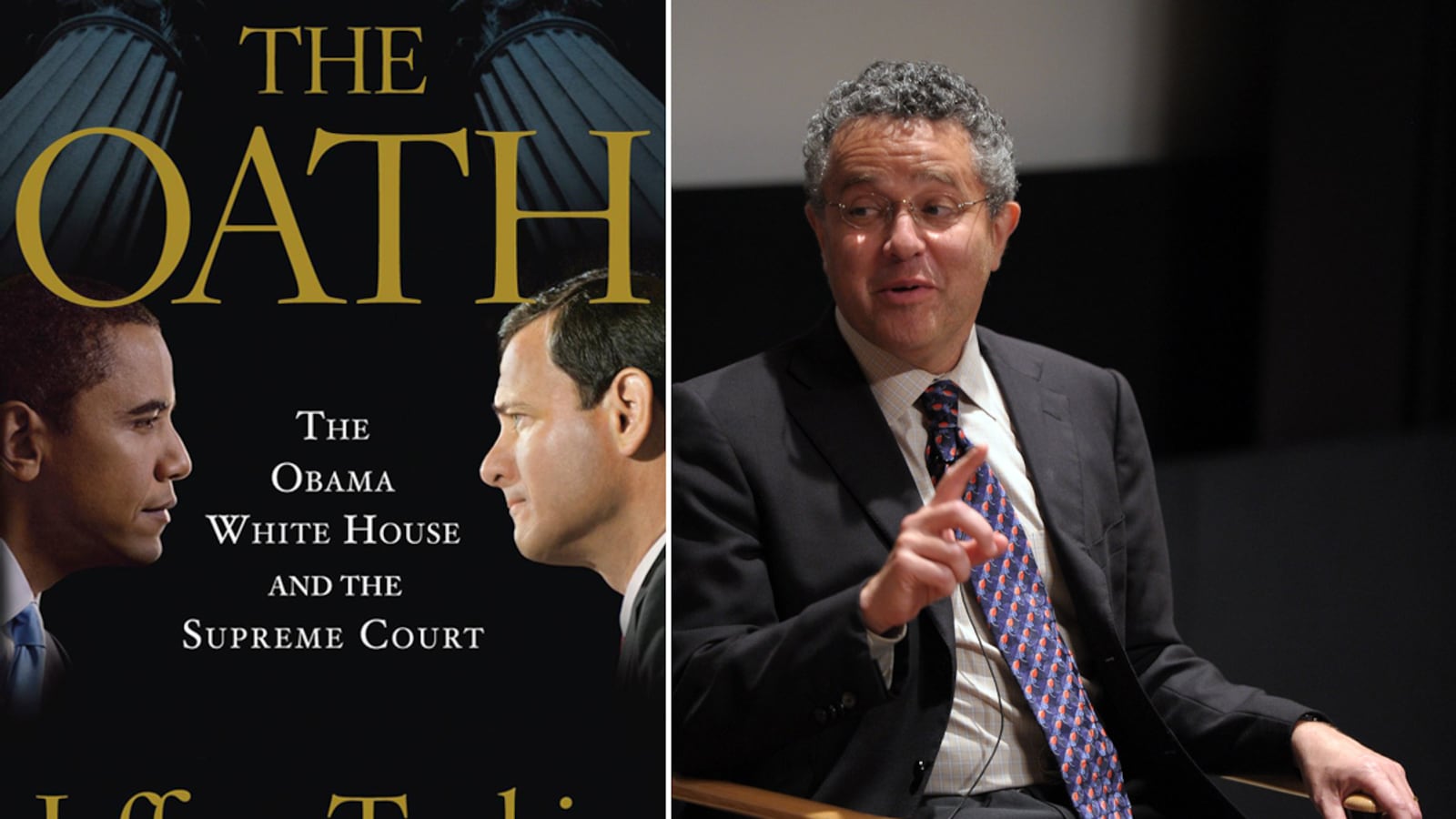

But let us go back before that day. Before the health-care ruling, John Roberts was the stealth hardliner, the activist judge par excellence. At the age of 57, he could for many more years carry the conservative legacy of George W. Bush, the man who appointed him as chief justice of the Supreme Court in 2005. He towers above his colleagues in his intelligence, savvy, and understanding of history. Jeffrey Toobin, the always clear-eyed legal-affairs writer for The New Yorker, seems like the man most likely to give us a measured, studied portrait of the justice. And Toobin shows us, in The Oath: The Obama White House and the Supreme Court, that Roberts has a partisan agenda—even a Republican agenda. He is “an apostle of change” who sees the Constitution in a very different way than previous justices have, and his assault on the precedence of the Court would be heavy. For liberals, this is a frightening look at a man who has the power to shape American lives for decades.

President Barack Obama, on the other hand, is the mirror image, his liberal intellectual equal. The clash of these two titans tugs America’s political and social future to and fro on issues from campaign finance, health care, abortion, affirmative action, gay marriage, to the nature of the Court itself. Fairly early in book, Toobin breaks down the differences between the two men: “One believed in change; the other in stability. One looked forward; the other harkened back. One was, in a real sense, a visionary; the other was, when it came to the law, a conservative.”

The punch line is that the one who believes in change, who looks forward, who is the visionary, is Roberts. “He was the one who wanted to usher in a new understanding of the Constitution, with dramatic implications for both the law and the larger society,” Toobin writes. It was Obama “who was determined to hold on to an older version of the meaning of the Constitution. Obama was the fellow who was, in the words of a famous conservative, standing athwart history yelling ‘Stop!’”

The fiercest battleground in this war was Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. On March 24, 2009, the writing was on the wall that the conservatives on the Court would be joined by Justice Anthony Kennedy in overturning the McCain-Feingold Act, striking down the ban on corporate contributions to political campaigns. The question was whether the justices would do it narrowly, in a decision that would just pertain only to the Citizens United case, or if they could issue a sweeping ruling, which would rewrite decades of constitutional law.

Roberts assigned himself the majority, and he initially wrote a narrow opinion, knowing that a sweeping ruling would shock the liberals and divide the Court. Kennedy was given the concurring opinion, which said the Court should have gone much further. But Roberts witnessed most of the conservatives rallying to Kennedy’s resolution, and under pressure, he withdrew his text, making Kennedy’s the majority opinion.

Sure enough, the liberals were shocked. Justice David Souter was in the final weeks of his tenure on the Court. “The Kennedy opinion reflected everything Souter had come to loathe about the Roberts Court—its disrespect for precedent, its grasping conservatism, its aggressive pursuit of political objectives,” Toobin writes. “Souter wrote a dissent that aired some of the Court’s dirty laundry. The dissent, had it been published, would have been an extraordinary, bridge-burning farewell to the Court by Souter.”

Roberts, Toobin says, doesn’t mind spirited disagreement over a case. “But he worried that Souter’s attack might damage the Court’s credibility, or his own. So the chief came up with a stroke of strategic genius.” In a clever move, he agreed to withdraw the sweeping majority opinion, and put Citizens United down for re-argument—a very rare thing—in September.

Turns out, the decision, given on January 21, 2010, was just as sweeping and (to liberals) controversial, but by then Souter was no longer on the Court.

It was the kind of cunning that people have come to expect from Roberts. David Axelrod, Obama’s top adviser, understood the implications of Citizens United, and was so incensed by the ruling that he wanted Obama to attack it from the bully pulpit—in fact, from the biggest one available: the State of the Union address, which would be delivered just six days later. Axelrod convened a meeting to make sure that he was on solid ground attacking the decision for opening the floodgates to campaign contributions from foreign corporations. “Sure enough, he was told.” The “sure enough” led to one of Obama’s most memorable moments in office, when he castigated the Roberts Court during his address, and Justice Samuel Alito shook his head and mouthed, “Not true” to the foreign corporations accusation.

But Toobin also tells of moments of shared respect as well. When Roberts invited Obama to tour the Court building six days before his inauguration, the president “lingered by the simple rectangular wooden table, with its nine chairs, that is the tangible symbol of the world of the Court,” Toobin writes. “Is this where they decided Brown?” Obama asked. Indeed it was, Roberts told him, in a moving moment of tribute to the landmark civil rights case that made a day like that possible.

The problem with the Roberts-as-Darth-Vader narrative is, of course, the health-care decision, which surprised everyone. In a game of prediction from hindsight, Toobin claims that a clue about the ruling came on June 15, 2012, when Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg spoke to the American Constitution Society. The year, she said, “has been more than usually taxing.” A fine and appropriate word to use for the occasion, but to Toobin augured yet another cunning Roberts turn—that he’d uphold the health-care mandate with the excuse that Congress has the authority to tax.

Toobin rationalizes that Roberts made the pro-Obamacare decision to maintain the Court’s reputation. This, however, complicates his thesis that Roberts is a man of fierce partisan activism who adheres only to the Republican platform. All of a sudden he has a huge respect for the Court’s precedence? All of a sudden he’s the one “standing athwart history yelling ‘Stop!’”? Perhaps maintaining the Court’s integrity trumped his agenda, but in the end you’re once again left wondering: who is this guy? If Toobin can’t nail him down, who can? How dare Roberts throw a curveball like that?

And ruin a perfectly good book.