When Algerian commandos initiated a raid Thursday to free hostages being held at a remote natural-gas complex, it was apparently a surprise to the top levels of the Obama administration as well as America’s key international allies. American workers were believed to be at the sprawling facility, and while details remain sketchy, U.S. officials said Friday that at least one American was killed.

That Algeria didn’t inform the U.S.—much less collaborate with it—before launching the raid should come as no surprise. Since 9/11, both the Bush and Obama administrations have tried to cultivate a relationship with Algeria’s military, intelligence, and security ministries. There have been occasional successes. Algerian officers have trained with the U.S. military; U.S. intelligence agencies shared overhead imagery of Algeria’s vast border; and the two sides at times cooperated against a common enemy, al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the group’s North African affiliate.

But in general, distrust has been a hallmark of the strained relationship between the U.S. and Algeria. Under President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the Algerian military has never agreed to the large kinds of defense aid packages other North African allies like Morocco and Egypt accepted. Known as foreign military financing, these kinds of grants can theoretically give the U.S. leverage over—and insight into—foreign militaries. (Algeria’s primary weapons supplier is Moscow, a relationship that goes back to the Cold War, when the Russians trained Algeria’s intelligence service and military.)

Algeria has also at times chafed at U.S. decisions. In January 2010, the Transportation Security Administration included Algeria on a watch list of national passports that would receive more scrutiny at airports following the attempted bombing of a Northwest Airlines flight from Amsterdam to Detroit on Dec. 25, 2009.

A few weeks later, the Algerian government formally protested the TSA decision, according to a Jan. 6, 2010, State Department cable since disclosed by WikiLeaks. That cable also said that in a separate meeting the day before, the Algerian government approved the over flight of U.S. EP-3 spy planes in the Sahel region of the country to monitor AQIM strongholds.

“They want overhead imagery, access to intelligence to control that vast space. We did help them to an extent in this realm,” says Ian Lesser, a senior director for foreign and security policy for the U.S. German Marshall Fund, a U.S.-based think tank and an expert in Algeria. “But in terms of military to military cooperation, we do not have the decades and years of joint training and exchanges…we have with other countries in the region.”

Since 2008, the U.S. has spent about $1 million a year from the International Military Education and Training Program to bring Algerian military officers to the United States for advanced military education. These exchanges are meant to give U.S. military officers a personal relationship with the future leaders of foreign militaries. Gen. Ashfaq Kayani, the chief of staff for Pakistan’s military, for example, studied at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. When he was there, he got to know a young officer named David Petraeus, who would go on to lead the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Algerian government also participated in military exchanges with the U.S., yet it wasn’t entirely convinced that the U.S. could teach it military and police about how to fight terrorists, according to current and former U.S. officials who worked on the program. In the 1990s, the Algerian government led a brutal campaign against the Islamist insurgency that eventually morphed into AQIM.

Geoff Porter, the president of North Africa Risk consulting, who has advised U.S. government clients and oil companies about political and security risks in Algeria, recalled a meeting in 2006 with Ali Tounsi, who was the director general of Algeria’s national police until he was murdered in 2010. Porter recalled how Tounsi said the U.S. “keeps extending invitations to visit Quantico or Paris Island, but they have nothing to offer that we don’t already know.” Porter added, “The view was Algeria had an extremely bloody counter-insurgency, and then after September 11, the United States launches its war on terror and comes parading all these goodies like counterterrorism cooperation.”

One recently retired U.S. intelligence officer who worked with Algeria’s intelligence ministries closely said that after 9-11, Algeria provided the U.S. with a list of more than 3,000 individuals it said had ties to al Qaeda and other jihadist factions. “Maybe 500 had some kind of connection,” this official said. “But the other 2,500 were just guys they didn’t like.”

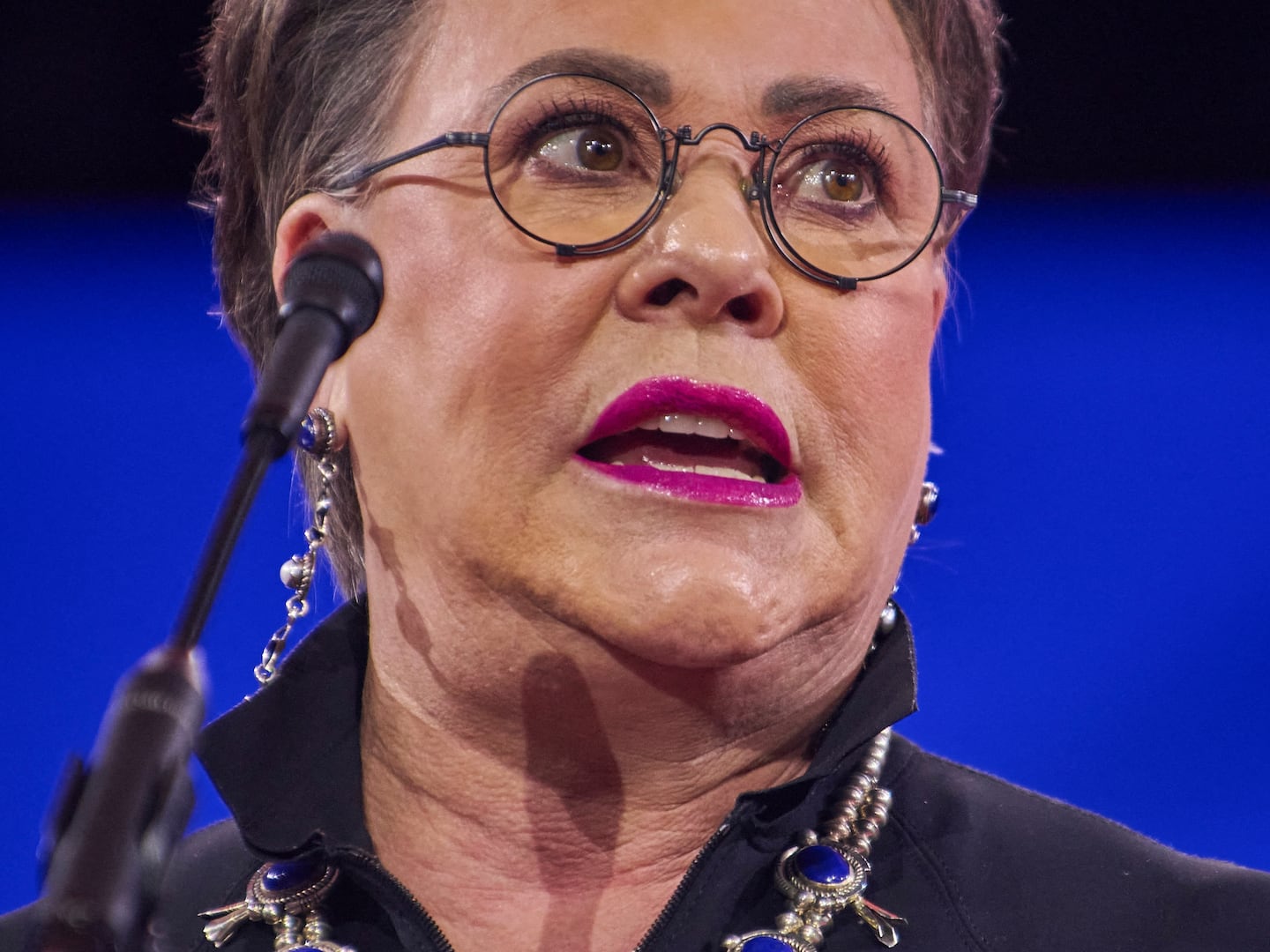

In the last six months, the Obama administration has intensified its diplomacy with Algeria in light of the deteriorating situation in Mali. Outgoing secretary of state Hillary Clinton has spearheaded an effort with the Algerian government to form a new strategic dialogue to broaden the relationship beyond counter-terrorism. But the emphasis has been on closing Algeria’s border with Mali and targeting the mix of ethnic rebels and jihadists who are threatening to turn Mali into the next major al Qaeda safe haven.

To some extent, these efforts have been successful. Algeria allowed France, its former colonial master, to use its airspace for the new military initiative in Mali. The Algerians also moved troops to the Mali border after initially resisting the recommendation, according to three current U.S. officials. But the wariness nonetheless remains.