America’s on-again, off-again support for the International Criminal Court over the years will likely complicate any role it takes in the investigation of atrocities in Ukraine, experts in international law and crimes against humanity told The Daily Beast. And the potential pursuit of war crimes charges against Russian leaders could stretch the Biden administration’s commitment to justice to its limits.

“The International Criminal Court and the United States have had a stormy relationship,” said Professor Leila Nadya Sadat, one of the world’s leading experts on crimes against humanity and a professor of international criminal law at the Washington University School of Law. “The United States can still play a material role, but it can’t offer the kind of major financial and logistical support that it could with the Yugoslavia tribunal, for example.”

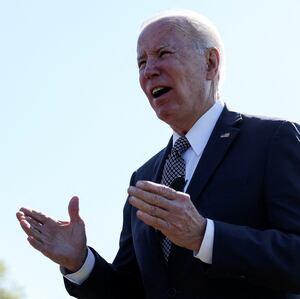

The entire civilized world has seen clear evidence of atrocities committed by Russian forces against unarmed civilians in Ukraine. Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced that the U.S. government has confirmed them, and President Joe Biden has declared that Vladimir Putin should be prosecuted for them.

But the outrage expressed by the Biden administration in response to the apparent massacre of hundreds of Ukrainian civilians in the city of Bucha, experts and lawmakers told The Daily Beast, can only go so far.

“It would be easier if the U.S. leaned in and signed the Rome Statute—it would make the position more forcibly based on values and the pursuit of justice,” said Fred Abrahams, an associate program director with Human Rights Watch who has documented war crimes for decades, referring to the international treaty that established the International Criminal Court. “It would say, ‘We’re not doing this because of some political aim’—the goal is to hold perpetrators of war crimes to account.”

The troubled history between the U.S. and the ICC—the Obama administration stepped up assistance for investigations of potential war crimes in Syria, while the Trump administration sanctioned the court’s top prosecutor—complicates what should be a straightforward matter of supporting human rights, Abrahams said.

The International Criminal Court has already begun the work of gathering evidence for potential war crimes charges against Russian military and government leaders—an effort that the Biden administration has pledged to support.

“There has to be accountability for these war crimes,” National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan told reporters on Monday, noting that the U.S. had coordinated efforts with the ICC in the past, despite not being a signatory. “That accountability has to be felt at every level of the Russian system, and the United States will work with the international community to ensure that accountability is applied at the appropriate time.”

But international human rights organizations, as well as members of Congress, are starting to push for the Biden administration to put its full weight behind investigations that could someday hold Putin accountable.

“I think we can’t ask for accountability if we have delegitimized the bodies that would be doing that accountability,” Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-MN), a member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, told The Daily Beast. Omar has previously introduced legislation that would prompt the United States to ratify the Rome Statute—and vowed to push the Biden administration to support its ratification in the coming days.

“It doesn’t bode well with the fact that we are now saying we want the ICC to do these investigations,” Omar said.

The calls come amidst a flood of images, videos and firsthand accounts from Bucha, a city just outside of Kyiv where authorities and journalists have observed mass graves of Ukrainians allegedly shot by Russian troops. Satellite imagery shared with The Daily Beast early this week shows a 45-foot-long trench in the city serving as a mass grave.

And even though the images are jarring, the United States’ role in pursuing prosecutions may turn out to be limited.

“To put it in a nutshell, the U.S. can assist with providing evidence for specific cases. They can also provide certain kinds of assistance, like witness relocation,” said Alex Whiting, a visiting professor at Harvard Law School and an expert on international criminal prosecution issues. “But it cannot, for example, provide funding or pay for prosecutors or investigators to go to the Hague.”

Linda Greenfield, the U.S. ambassador to the UN, called for Russia to be suspended from the United Nations Human Rights Council on Tuesday morning, a first step to reducing its influence at the international organization—but that’s not enough, said Rep. Lee Zeldin (R-N.Y.). Next, the United States ought to move to kick Russia out of the UN Security Council, Zeldin told The Daily Beast.

“Russia—[and] Putin specifically—has earned that consequence for Putin’s invasion of Ukraine,” said Zeldin, who serves on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, warning that the steps the Biden administration takes against Putin must be strong and decisive.

Otherwise, Putin will keep going, running his massacre possibly beyond Ukraine.

“If Putin isn’t held accountable… he’s someone with ambition to commit additional crimes against humanity, potentially in other countries,” Zeldin warned.

The Biden administration’s agreement to assist in investigating potential crimes in Ukraine is no small thing—particularly when the crime scene effectively stretches across a country nearly the size of Texas.

“Where the United States can play a substantial role is in helping to organize that information,” said Sadat. “That is going to take a lot of person-power in order to process and organize evidence and be able to use all of that information. That is where the United States, which has some expertise in this, is able to do that.”

“You have to think of what’s happening in Ukraine as an incredibly complex crime scene,” echoed Abrahams. “The bodies that are out on the street—we’ve all seen these photos and videos—they should record the wounds, try and photograph the bodies, document the cause of death. Then you’ve got the witness statements, then you’ve got the ballistics analysis, and then you’ve got the big question: who done it?”

“All of that takes time.”

But the timeline for an investigation leading to a prosecution—even one in absentia—could take years, said Dr. Courtney Hillebrecht, a professor of international relations at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and an expert in human rights.

“These are incredibly difficult tasks under the best of circumstances, and these are obviously not the best of circumstances,” Hillebrecht said. “Justice will not be forthcoming in the immediate term. We are talking years, not weeks or months.”

White House press secretary Jen Psaki admitted as much in a briefing on Tuesday, emphasizing U.S. economic sanctions as its primary mechanism for punishing Russian war crimes in the near term. But that timeline is too slow for many of Biden’s Democratic allies on the Hill, some of whom are now pushing for the administration to expel Russia’s ambassador to the United States in response to the Bucha massacre.

“There are horrific war crimes being committed by the Russian forces. We need a response,” Rep. Ted Lieu (D-CA), a member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, told The Daily Beast. “The United States needs to expel the Russian ambassador to the United States.”

More broadly, international law experts expressed fear that America’s refusal to fully endorse the ICC risks making its support of a potential tribunal on Russian war crimes look like a strategic maneuver against a geopolitical foe, rather than a humanitarian action that would punish a moral obscenity.

“The U.S. is not a nonpartisan participant in this conflict. They’re delivering weapons to the Ukrainians and are politically clearly aligned, so there’s an issue of independence and perceptions of independence,” said Abrahams, who testified in the ICC’s war crimes trial of former Serbian president Slobodan Milošević. “In some ways, the U.S. is a party to this conflict—they’re not fighting, but they clearly have taken sides.”

“That puts them in a bind. It’s a thin line for them to walk.”

Despite the long arc of justice on crimes against humanity, authorities on international criminal law are guardedly optimistic that the perpetrators of the Bucha massacre and other potential war crimes will be identified and prosecuted, one way or another.

“Assuming that the West stays unified, there will be arrests and there will be justice,” said Sadat.

Whether that justice will be hastened by a real U.S. commitment to enforcing international law in Ukraine, however, remains unclear.