Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes,The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places.

It is timely to recall, on this Easter weekend, that Pope Francis is often called “the Pope of mercy.” He has spoken many times about putting an emphasis on mercy in the spiritual life, and indeed at the beginning of Lent he proclaimed a “Jubilee Year of Mercy.”

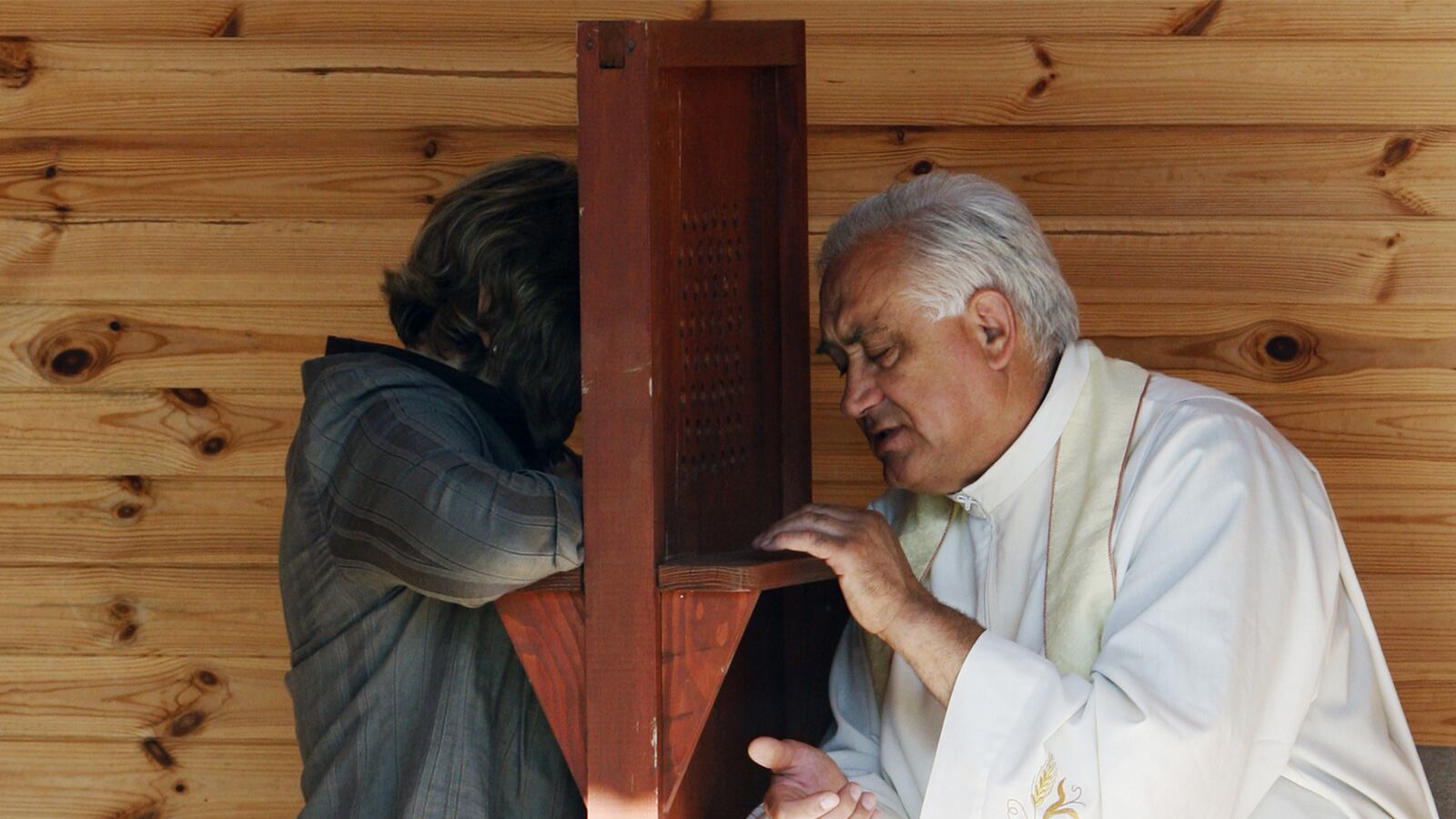

One way that Pope Francis has highlighted the importance of mercy is through one of the most important and beautiful sacraments of the Catholic Church: the sacrament of confession. In his first Mass as bishop of Rome in a Roman church, Francis arrived early and unannounced to hear the confessions of the parishioners. He has also heard confessions during World Youth Day. And he has also, himself, publicly gone to confession several times in Saint Peter’s basilica. (All Popes regularly go to confession, but Francis has smartly decided to make an example out of it.)

Lent, which ends this Sunday, is famously a time of penance. But the main way this is traditionally done for Catholics is not principally through giving up chocolate. It’s through going to confession, especially in the days before Easter. Why is confession so important for Catholics?

Well, first, it is a sacrament. Catholics believe that God is so generous that when Jesus came to Earth, he gave the Church he founded “visible signs of grace,” meaning certain rites that are guaranteed to work out certain spiritual effects. Confession is one such sacrament: Although Christians can confess their sins privately, a valid confession guarantees the forgiveness of sin.

Secondly, well, we all need to get something off our chests once in a while. And sometimes—more often than we suspect, perhaps—we have things that we’re not comfortable saying even to our closest friends and family. The absolute sacredness of the seal of confession guarantees that what you’re saying will never get out, and the anonymity of confession makes it easier to get these things off your chest.

But confession is also a spiritual and psychological crucible that makes us stronger. The number one thing we humans don’t like to do is to look at our failings, look at all the ways we’ve come up short, look at our flaws—and look them in the eye. And this even as we know that it’s impossible to grow and be healthy if we’re not able to do that. Through the examination of conscience and the priest, we are able to truly confront what ails us and to get past it—and receive the forgiveness of an infinitely merciful God.

Confession, in the end, is what joins us closer to God, which is what the Christian life is all about. The great mystic and Doctor of the Church Saint John of the Cross used the analogy of God’s grace as the sun shining into the room of our soul through a window. Sometimes, we think the sun has stopped shining—but it always shines, and it is just the window that has been dirtied up by our sins. Confession is the greatest window cleaner there is.

But this is also why so few Catholics go to confession—probably even fewer than go to Mass every Sunday, which is already a minority. Confession, when done right, is a crucible. A cleansing confession feels unutterably good afterwards, even if it can feel horrible during.

Many Catholics, your writer certainly very much included, often get into a vicious cycle: The longer one waits to go to confession, the more sins accumulate; the more sins accumulate, the harder it is to go to confession; the harder it is to go to confession, the longer we wait. And the burden on our shoulders only gets heavier and heavier—but the feeling of having it lifted off when one does go is incomparable.

This is why good pastors, from the Pope on down, frequently exhort people to go to confession: it’s hard to go, but it does us so much good. As the busiest week of the year for confessions reaches its culmination, it’s good for all of us to be reminded.